A proper examination of the history of Yosemite National Park takes us back to the summer of 1855, when the Yosemite Valley received a visitor from far away. This gentleman had heard rumors of the great valley, and held grand plans for the newly publicized area.

His efforts to advertise Yosemite would effectively bring the first notoriety to the area, and would unwittingly lead to its preservation as a the nation’s first park only nine years later. You may think his name was Muir, but it wasn’t…

Guide to Yosemite

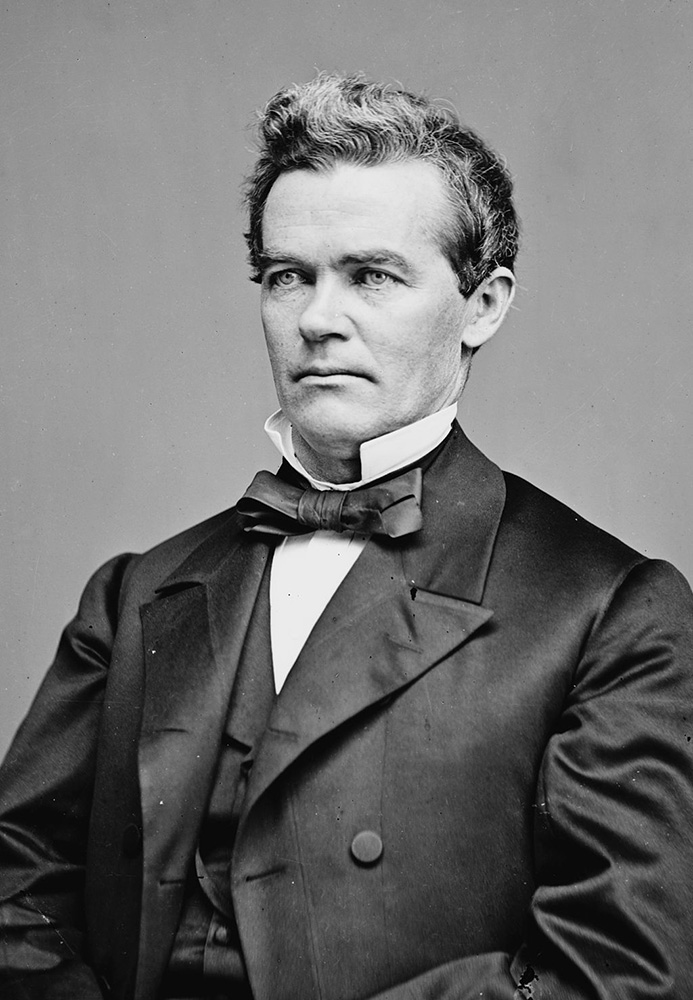

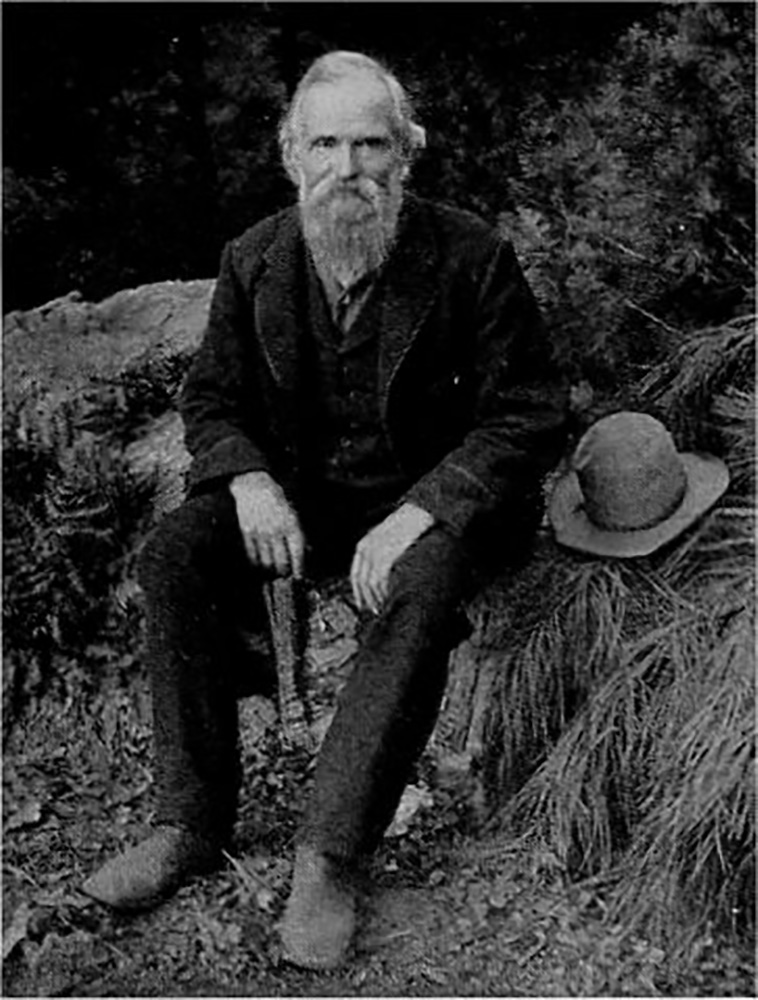

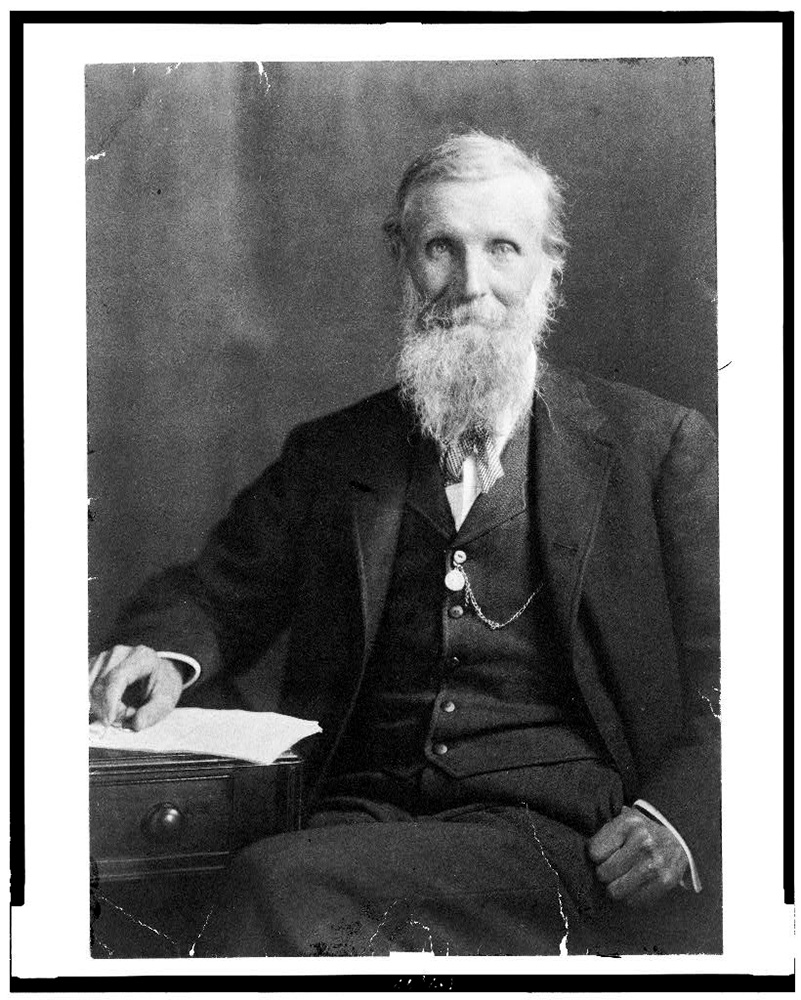

James Hutchings

James Mason Hutchings was an English immigrant to the US who had quickly crossed the young nation and landed in San Francisco during the mining boom of the 1849. He had read in local newspapers, reports of the Mariposa Battalion, which made note of a great waterfall that stood in excess of 1,000 feet high, in a remote unknown region called Yosemite.

The eager Englishman had a knack for publishing, having already produced “The Miner’s Ten Commandments” which had sold more than 100,000 copies. Realizing the success of this venture, he began contemplating the publication of a tourism-based magazine that would promote travel in the state of California.

Public Domain Image*

Such an unlikely scene as a 1,000 foot waterfall in a lush valley of unparalleled beauty, if captured by an artistic image that could be reprinted in his magazine, would ensure sales of his new publication.

With this in mind, he recruited Thomas A. Ayres, an emerging San Francisco artist, to join the expedition and create visual representations of the stunning scenery, which could then be transferred into images for the future magazine.

Hutchings’ First Yosemite Visit

The journey to Yosemite proved difficult, as directions were nearly impossible to attain, even in the nearby town of Mariposa. Hutchings spoke with veterans of Savage’s military campaign, who surprisingly had difficulty recalling with any specificity the exact route into the remote valley. Finally, with the aid of two hired Indian guides, and four days of rugged travel, Hutchings and his crew arrived at Old Inspiration Point.

Later recounting his first Yosemite visit for an article in the Daily California Chronicle, Hutchings wrote:

“We had been out from Mariposa about four days, and the fatigue of the journey had made us weary and a little peevish, but when our eyes looked upon the almost terrific grandeur of this scene, all, all was forgotten.

‘I never expected to behold so beautiful a sight!’”

James Mason Hutchings

The group made their way from Old Inspiration Point into the valley below, arriving at its floor in the dark. They unrolled their blankets and slept in the open air, just beside an Indian trail. The party spent the next 5 days in the valley, exploring its waterfalls and meadows from one end to the other.

Upon their return to society, Hutchings wrote articles and Ayers published the first pictorial representations of what would become one of the most visually recognizable places on the planet.

It would be four years before Hutchings returned to Yosemite Valley. In his absence, his well-publicized, detailed descriptions of the area would influence a man whose failing health led him to seek a remedy in the great outdoors. This man felt that wild Yosemite may hold a cure for his ailments.

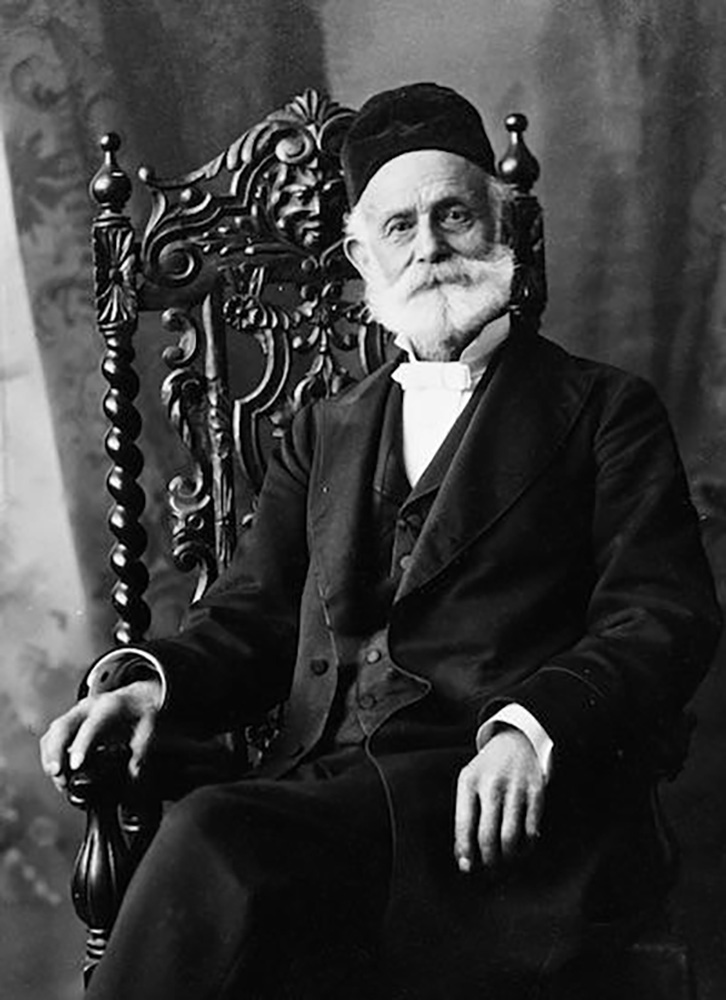

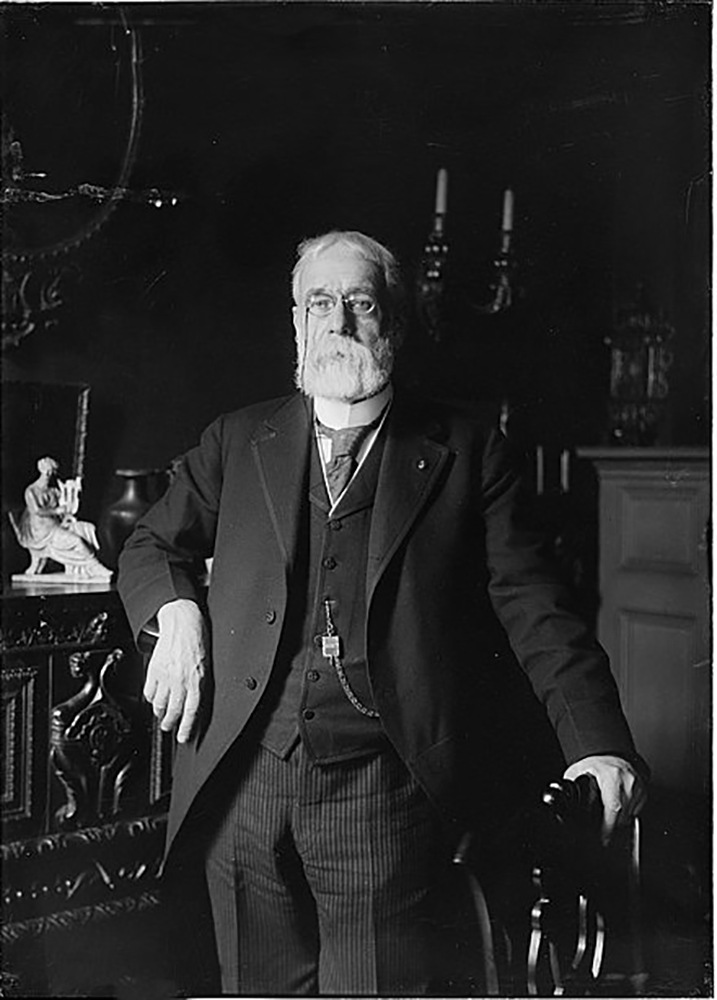

Galen Clark

Galen Clark, a native of New Hampshire, had led a life as a cabinet maker in Missouri, where he married and started a family. In 1845, he and his family moved to Philadelphia, where his wife would pass away in 1848, just nine days after giving birth to a son.

Mr Clark took his 5 children to live with relatives in Massachusetts, and headed for California via ship through the Isthmus of Panama, arriving in Mariposa in 1854. He took a job with the Mariposa Ditch Company, but within a few years found that he was extremely ill, suffering from lung hemorrhages so severe that doctors gave him a short time to live.

Public Domain Image*

At this time, Galen Clark was one of the few whom had seen Yosemite, touring the area in August of 1855, after reading descriptions of the scenic wonderland written by James Hutchings that were printed in the August 9, 1855 issue of the Mariposa Gazette, Clark’s hometown newspaper.

The vastness of the mountains and valleys had a profound effect upon the easterner. So much so, that when faced with a death verdict by doctors, Clark did what any self-respecting park junkie would do:

“I went to the mountains to take my chances of dying or growing better, which I thought were about even.”

Galen Clark

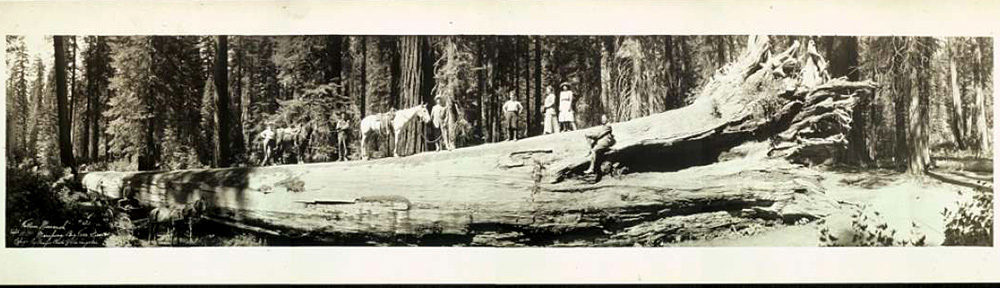

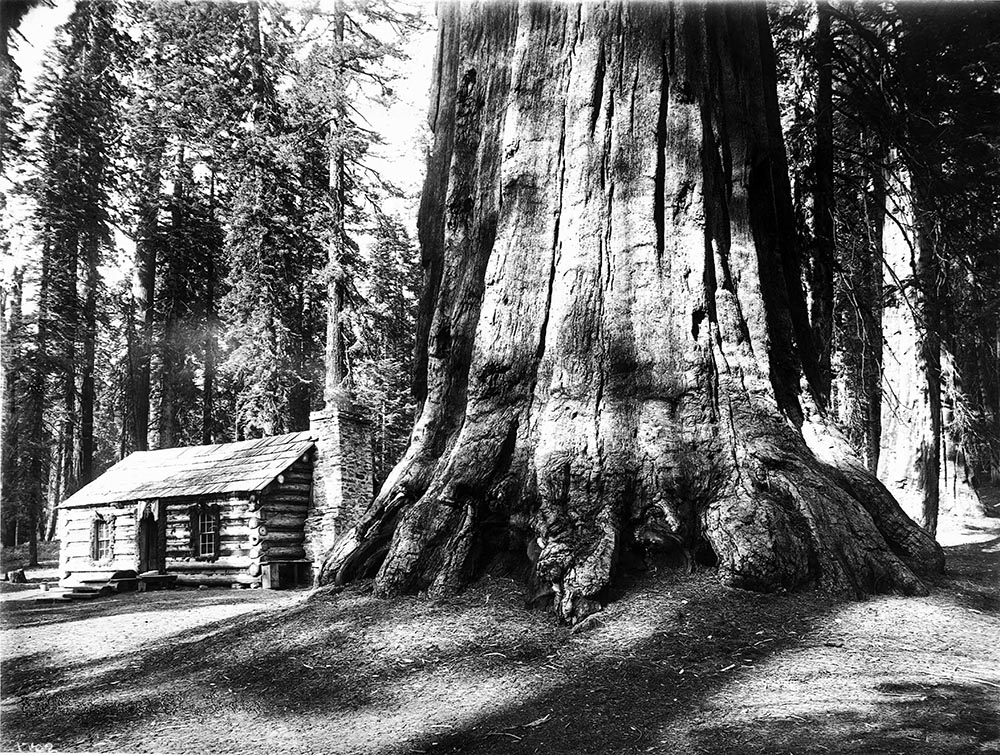

In 1857, Clark settled in the meadowlands of the Wawona area. He built a log cabin near the river and set out to live his life among the trees. Soon in his wanderings in the area, he found a great grove filled with hundreds of giant Sequoia trees that he named the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees.

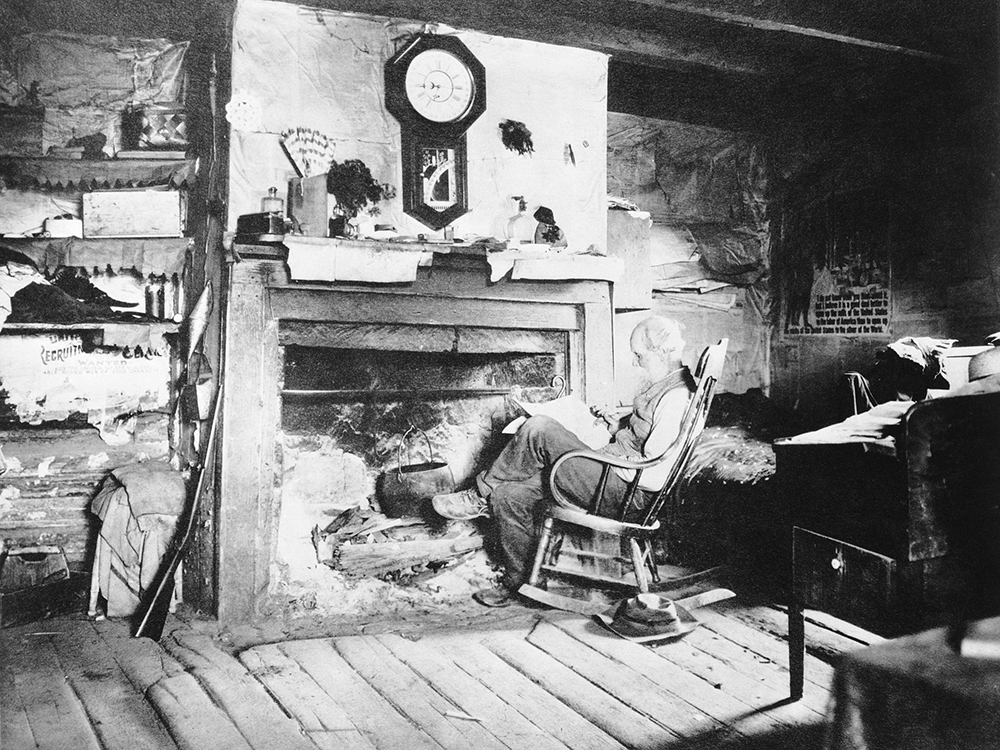

By 1864, he had built a small cabin where he greeted a growing number of visitors at what soon became known as Clark’s Station. Here he lived, hunting, reading and writing, counting and measuring the big trees, and entertaining guests with stories and lessons on everything from flora and fauna to local Indian history and geology.

Origins of the Park Idea

At the same time, in Washington DC, on the opposite shore of a nation embroiled in a brutal Civil War, a unique idea was quietly making its way through the halls of Congress.

On May 17, 1864, California Senator John Conness took the floor of the Senate chamber to briefly explain a bill to which little attention was paid. The bill, known as the Yosemite Grant Act, was unprecedented not only in the history of the young nation, but in the history of humanity itself.

Public Domain Image*

The bill proposed the eternal preservation of a group of giant trees and a valley filled with scenic beauty somewhere in the remote and unknown wilderness of California. The land in question was designated to be granted to the State of California, under the express condition that the “premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation”.

What, or who, led Sen. Conness to propose this bill is still the subject of some mystery. He merely stated on the Senate floor that he was acting at the urging of some of his constituents, “various gentlemen of California”, and “gentlemen of fortune, of taste and refinement”. Names of these refined gentlemen were never given.

The only name that ever is associated with the idea to promote this area as a protected area is that of Israel Ward Raymond, of the Central American Steamboat Transit Company. His (and his allies’) interest in the area likely would come from the realization of tourists dollars through travel to the park. This would become common in future decades, as railway conglomerates scrambled to create new reasons for travelers to seek their services.

After a couple of innocent questions, Conness assured the Senate that the area was worthless, and that no federal money was to be spent. The bill passed without objection, and the Senate moved on to the more pressing matters of wartime.

A month later, the House passed the bill and the Yosemite Grant Act moved on to the desk of President Abraham Lincoln, who signed it into law on June 30, 1864, less than a year before he would die at the hands of an assassin.

What is a Park?

The newly protected land would now require a guardian, someone to maintain roads and bridges, oversee the number of hotels and businesses that began popping up, provide information to guests and to prevent those same guests from loving the land to death by ruining the very sights they had traveled so far to enjoy.

Upon the official transfer of the land grant to the state of California, the sum of $500 per year was set aside to pay for such administrative tasks. The management of the grant was to be locally administered by a Guardian, who would act as an on-the-ground representative of an eight-man board, the Yosemite Park Commission.

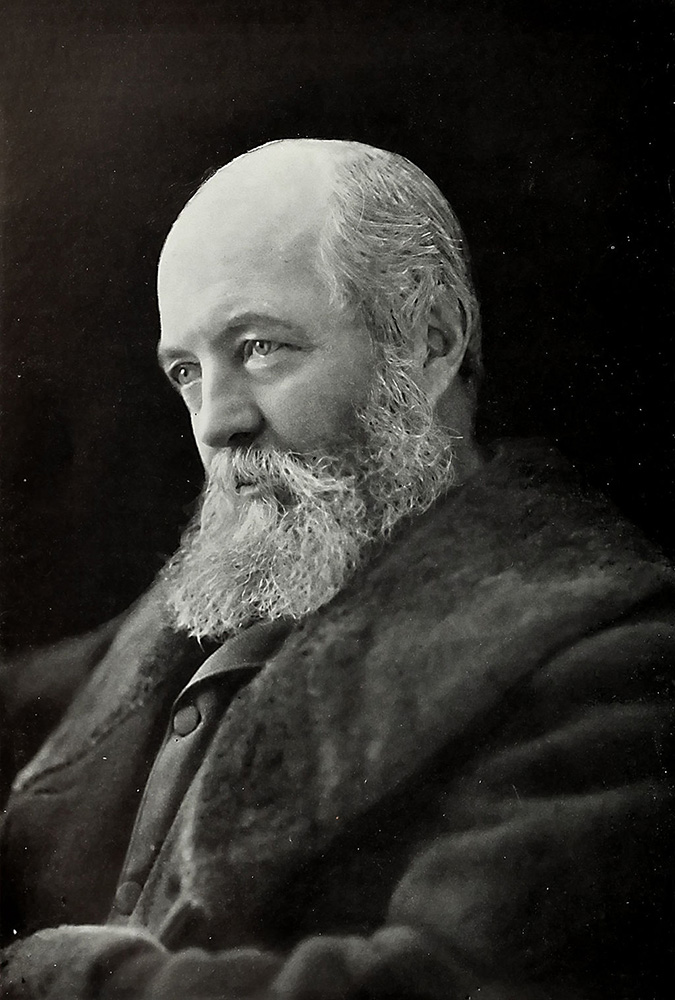

Fredrick Law Olmsted & Yosemite

One of the 8 commissioners was Fredrick Law Olmsted, a landscape architect and designer of Central Park in New York City. Olmsted immediately arranged for surveys of the Valley, paying the fees from his own pocket. He presented a detailed report to the commission which essentially foretold the ideals of what would one day become national park management standards.

“It is the will of the nation as embodied in the act of Congress, that this scenery never shall be private property,” he noted, “it shall be held solely for public purposes”. Building on this point, he observed that the very reason for the park designation was based on its visual appeal. From this the architect summed up what would eventually embody park management ideals.

“The first point to be kept in mind then, is the preservation and maintenance as exactly as is possible of the natural scenery.”

Essentially, Olmsted was suggesting that if the park was to be maintained as a natural park, strict restrictions should surround the approval and construction of all man-made structures and that their impact on the surrounding area should be of minimal influence.

Public Domain Image*

These were somewhat radical ideas at the time, natural conservation was not really a thing. The broad consensus of the day, was to improve on nature, not to preserve it. It is possible that part of Olmsted’s reason for stating his views on this subject, centered around the few existing haphazardly arranged structures that stood in the valley at that time, that likely did not suit his orderly appeal.

Upon the submission of this report to the commission, Olmsted departed and returned to New York. Although he would in the future advocate for further preservation efforts in the area, he would never again visit Yosemite.

Olmsted would one day be heralded as a visionary, accurately predicting that although Yosemite’s visitation in the 1860s was measured in the hundreds, it would soon “become thousands and in a century the whole number of visitors will be counted by the millions”

His belief in the inevitable popularity of the area led him to issue a warning concerning the management of the newly designated park: “An injury to the scenery so slight that it may be unheeded by any visitor now, will be one of deplorable magnitude when its effect upon each visitor’s enjoyment is multiplied by these millions.”

Other members were of particular influential circles as well. Josiah Whitney and William Ashburner of the California State Geological Survey and Israel Ward Raymond, who had originally penned the letter to the US Congress in support of the park idea.

For reasons that are the subject of query to this day, Olmsted’s report was shelved, or more accurately, buried. Evidence of the report surfaced in 1952, when copies of the document were uncovered by his biographer, Laura Wood Roper. It is suspected that Whitney and Ashburner bore the majority of the responsibility of the report’s disappearance.

For better or worse, ignoring the suggestions of Olmsted, the commission moved forward. There were no existing instructional manuals (save the one Olmsted just presented them) concerning the management natural areas such as the Valley and the Mariposa Grove. The commission was essentially winging it. They would certainly need a man on the ground.

The Guardian of Yosemite

There was an obvious choice for the position. A man was already there of his own will, hosting visitors, providing lodging, meals and directions, all while detailing the sights and educating guests on geology and the history of the area.

Galen Clark was feeling better now, his health problems seemed to fade upon his retreat from the rat race and he had become quite content living in the quiet forests near the Big Trees.

Public Domain Image*

The eight-man board of commissioners unanimously selected Mr. Clark to become the caretaker of his beloved trees and nearby valley. There were nearly sixty-square-miles to be protected, and Clark knew the area well. He took the job, a position he would hold for the next 24 years. With his acceptance of these tasks, Galen Clark essentially became the world’s first park ranger, known then as the Guardian of Yosemite.

Dueling Interests

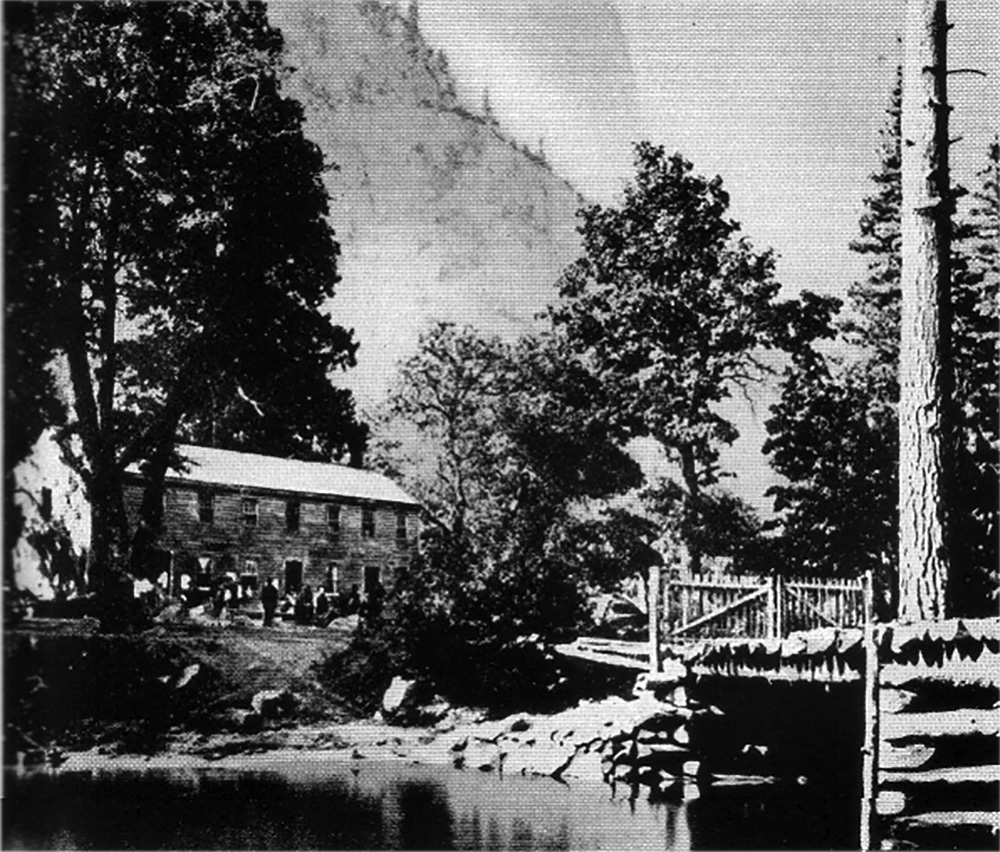

By this time, Yosemite Valley had taken a new resident. James Mason Hutchings had returned to his extolled kingdom of waterfalls and wonder, and he made it clear thats his intent was to stay and set up shop.

Hutchings quickly went about expanding operations in the valley, and soon owned two hotels, one famously known as the Hutchings House, and began charging people to see the park. He built a cabin for his family and soon began plans to expand operations with the construction of a sawmill that would provide the timber necessary to add rooms to his hotels.

Public Domain Image*

Unfortunately for Hutchings, he was technically squatting on the land, as it had never been officially surveyed or opened for settlement. He held no legal title to the land upon which he resided and operated business.

While the same could have been argued for Galen Clark’s cabin prior to the land grant, the latter now had express right to exist on the land, as official Guardian, sanctioned by the government.

Offers were made to Hutchings so that he could maintain his holdings in the Valley. Clark, through the Yosemite Park Commission, had given the embattled entrepreneur the opportunity to retain his hotels under a government lease, for the sum of one dollar per year. Yet, for some reason, he stubbornly refused to recognize the Congressional decision to make the land a public park..

Thus, a feud began between the two residents of Yosemite, which eventually placed Hutchings in fierce legal battles with the government. Despite the opposition, he remained defiant and continued his expansion efforts in the valley, ignoring demands to cease his operations. The sawmill idea was moving forward, and he needed someone to build and operate it.

John Muir

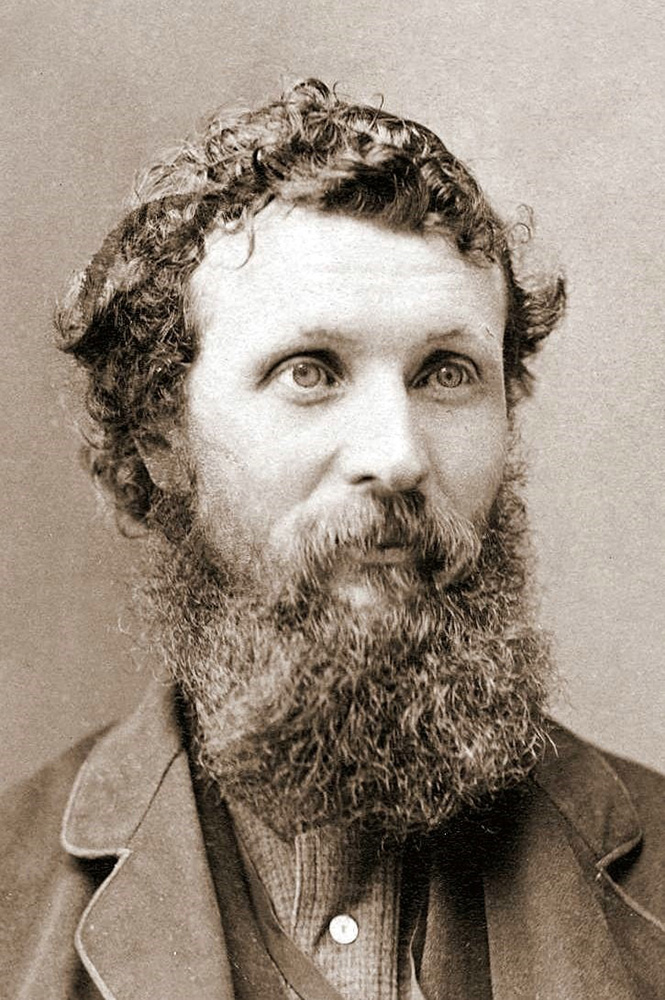

The summer of 1869 had welcomed a newcomer to the mountains of the Sierra Nevada. A Scottish-born wanderer with an adventurous spirit had found his way into the area, seeking an escape from the world of factories and “noisy commercial centers” that worried his very soul.

John Muir’s family immigrated to Wisconsin when he was eleven-years-old. His father was a strict Presbyterian minister, who insisted that young John memorize Biblical scripture. By the time the family came to America, the boy could recite the entire New Testament, and most of the Old Testament.

Photo-Carleton Watkins / Public Domain Image*

Muir was intellectually blessed and found his way into the University of Wisconsin, where he studied botany and geology. Soon however, the Civil War impressed upon the young man that it was time to head to Canada, where he spent two years.

At the war’s end, he returned to the states and worked a number of mundane jobs that left his spirit unfulfilled. Luckily for young Muir, while working in a factory, he suffered an eye injury that left him blinded for several months. Upon regaining his eyesight, he set out to live a life that he believed was more suitable to his spirit.

So he enrolled in what he referred to as the “University of the Wilderness” and set out to see the world…

First, he embarked on a thousand-mile walk, through the southern United States, which was recovering from a crushing defeat in the bloody Civil War, which had nearly destroyed the nation and devastated most of the southern infrastructure. Life was rough in the south during this time.

Along the way, he took time to make meticulous drawings and sketches of various plants that he encountered. He was in no hurry, eventually arriving in Florida, where he contracted a three-month-fever, likely due to malaria.

When he could not readily acquire passage to South America from Florida, he accepted the opportunity to head for California, deciding that he would investigate a strange land called Yosemite, which he had read about in a brochure.

Anywhere That’s Wild

Disembarking from a ship in San Francisco in 1868, he was asked where he wished to go. His reply: “Anywhere that’s wild.”

Soon, the young adventurer found his way to the Sierra Nevada, where in 1869 he acquired a job shepherding a flock of some 2,000 sheep in the high country for the sum of $30 per month.

That summer, he came upon Tuolumne Meadows and meticulously studied the area’s flora and fauna, later detailing many of his experiences in a published work “My First Summer in the Sierra”. He referred to these mountains as the “range of light” and wrote that his summer months spent in their meadows were, “the greatest of all the months of my life, the most truly, divinely free”.

In the fall of 1869, he finally descended into Yosemite Valley which he described as “the grandest of all the special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter”.

Public Domain Image*

Here he met James Mason Hutchings, who was searching for someone to assist in the expansion of his hotels, and to construct and operate the sawmill that would supply materials for construction. Muir had experience in a sawmill and was stoked to stay in the valley and make it his home.

Soon, he had constructed the sawmill and a cabin in which he and another worker would reside. The sawmill was constructed from fallen timber and proved quite effective, however it was the small one-room cabin that was Muir’s pride. He boasted that it cost him three or four dollars, but he considered it the “handsomest building in the Valley”.

It was erected near the base of Yosemite Falls and was floored with stones that were arranged such that ferns could grow between, while a small ditch diverted from a nearby creek brought water flowing through a corner of the cabin so that it would “sing and warble in low, sweet tones, delightful at night while I lay in bed”.

Muir spent his hours both working for Hutchings and exploring the valley and its surrounding mountains. Once his duties were completed, he would depart on journeys that sometimes kept him moving for days, wandering through the land, talking to rocks, trees and plants. And listening to their replies as part of what he described as his “unconditional surrender to Nature.”

“I drifted from rock to rock, from stream to stream, from grove to grove… When I discovered a new plant, I sat down beside it for a minute or a day, to make its acquaintance and hear what it had to tell… I asked the boulders I met, whence they came and whither they were going.”

John Muir

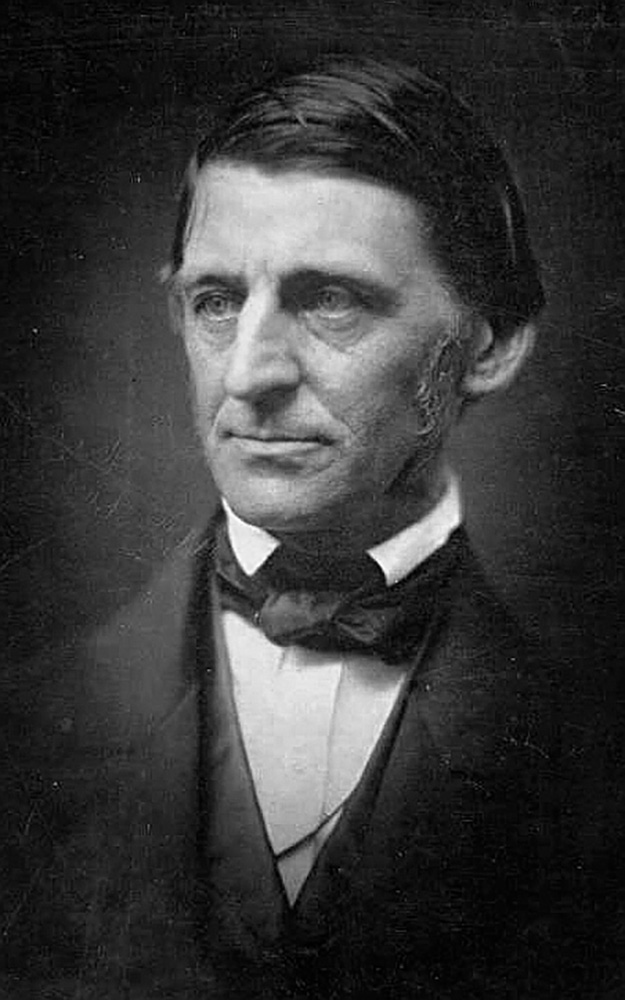

Muir soon became a legend in the valley and visitors often came for his nature walks and sought his expertise concerning the valley and surrounding mountains. As time passed, Hutchings, who seemed to desire such attention for himself, became increasingly jealous of the accolades that worldly guests such as Ralph Waldo Emerson bestowed upon the young Muir.

Emerson & Muir

An aging and somewhat frail Emerson visited the park in 1871. He and Muir, accompanied by Galen Clark, explored what Emerson would describe as Muir’s “mountain tabernacle” and the philosopher would one day enter Muir’s name on a list of the greatest men he had ever met.

Public Domain Image*

Emerson encouraged the naturalist to consider a move back into society where he could wield considerable influence through his writings and teachings about the natural world, reportedly even advancing the idea of arranging a professorship at Harvard if Muir would have it.

Others would suggest the same and Muir began to consider the option of extolling the virtues of nature to a larger audience than he could arrange in the limited social confines of Yosemite Valley. The would-be author did experience substantial success in his early efforts to bring more people to the temples of nature through the publication of articles in newspapers. Yet he yearned for greater influence and a more effective means of spreading the gospel of nature.

“Heaven knows,” wrote Muir” that John [the] Baptist was not more eager to get all his fellow sinners into the Jordan than I to baptize all of mine in the beauty of God’s mountains.”

John Muir

Muir & Clark

During his years in the valley, Muir would spent countless hours wandering the hills with Galen Clark, and the two became tight. Muir expressed his admiration of Clark and considered the park guardian to be the best mountaineer that he ever met.

The Scottish born naturalist was also impressed with Clark’s ability to make a home out of nothing, “He would lie down anywhere on any ground, rough or smooth, without taking pains event to remove cobbles or sharp-angled rocks protruding through the grass or gravel,” he noted of Clark.

Public Domain Image*

“He kindly furnished us with flour and a little sugar and tea, and my companion, who complained of the be-numbing poverty of a strictly vegetarian diet, gladly accepted Mr. Clark’s offer of a piece of bear that had just been killed.” wrote Muir of Clark’s hospitality.

By 1873, Muir’s relationship with James Mason Hutchings had soured and the two men had parted ways. Muir felt that the Englishman was shallow and vain. Likewise, the hotel proprietor had grown to resent the famed naturalist’s reputation as the superior expert on Yosemite Valley.

Soon Muir would depart the Yosemite Valley, and leave Clark to watch over nature’s temple and to take care of her guests.

Muir’s Writings

In November of that year, Muir left the valley and settled in Oakland to begin his writing career. Although somewhat intimidated at first, he appeared as determined as gravity to see his project through. Writing was, as he wrote, “like the life of a glacier, one eternal grind”.

Despite the grind, Muir excelled at detailing his accounts of natural occurrence and his published works became increasingly popular through the 1870s. He soon began to command some degree of political influence, as his writings were becoming more politically directed. He continually ripped California legislators for inaction in protecting wild habitat and woodlands with articles published both statewide, and nationally.

A Battle Brewing in the Valley

Meanwhile, on the ground in Yosemite Valley, James Mason Hutchings was becoming a problem for Galen Clark and the Yosemite Park Commission.

Numerous court proceedings had been undertaken. State legislators and courts were friendly to Hutchings, usually ruling in his favor, while the federal courts were unswayed by his arguments. If the governor vetoed the legislators, they would override him. Hutchings had made some friends…

Public Domain Image*

Hutchings was basically arguing that the government had no right to set aside portions of the public domain for any reason other than for settlement of its citizens. A California district court sided with him, however the State Supreme Court ruled against him. He then appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Here, the final blow against the embattled proprietor came in December 1872, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against his claim in the opinion of Hutchings v. Low, a case that ultimately set the precedent for the constitutionality of national parks.

The courts did however, award Hutchings and another claimant, James Lamon, who also held interest in the Valley monetary compensation to the tune of $24,000 and $12,000 respectively for improvements to the land. Despite the payout, Hutchings proved unmovable, and continued to reside in the Valley until he was finally evicted by the Mariposa County Sheriff in 1875.

He would then move to San Francisco with his family, where he would start his own tourist agency, give lectures and author two best-selling books about the park. Hutchings was indeed, the man who put Yosemite on the map and introduced the world to its wonders. He loved it, there can be little doubt. Despite his apparent despicably greedy disposition, Yosemite was his life…

In the coming decades, much would change in the American west. Railways were being built that moved the masses westward as never before. Lands that were previously known only to natives became overnight settlements and communities sprung up like wildflowers. The American dream was alive in the west. Through this rapid expansion, the somewhat novel idea of preserving wilderness for the sake of wilderness was slowly gaining adherents throughout the nation.

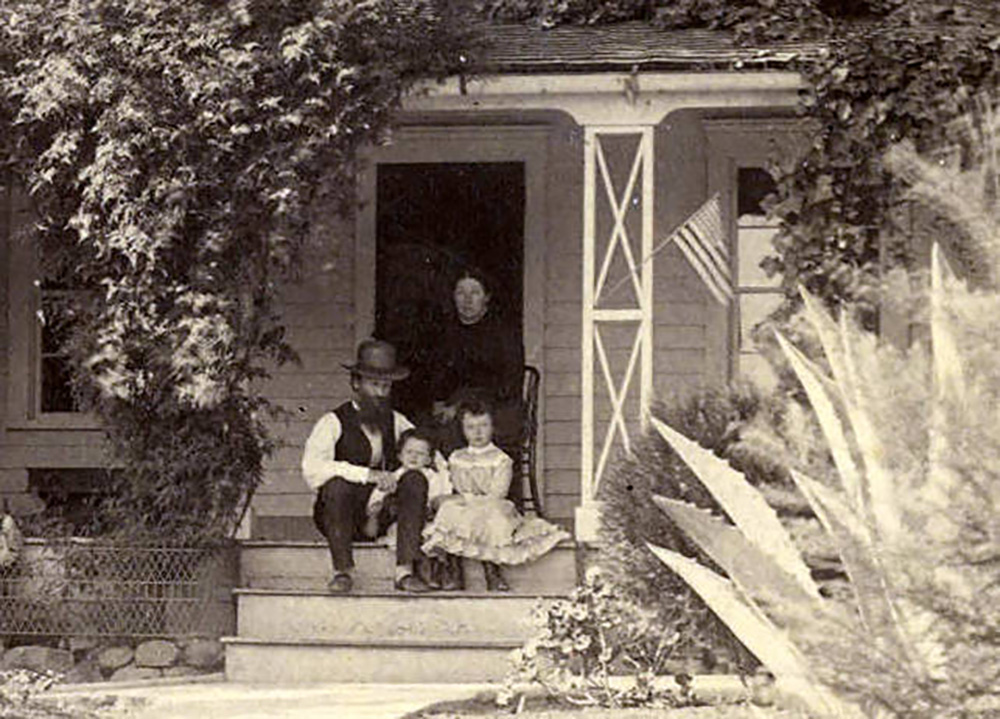

Muir the Family Man

During the 1880s, Muir’s dedication to his environmental efforts wained, due in part to his new family, and the responsibilities of a family man.

The middle-aged drifter married Louisa Strentzel in 1880, a younger lady whose well-to-do family owned a fruit orchard in Martinez, California. Muir assumed much of the responsibility for the 3,000 acres ranch’s operation and proved quite successful at the craft, increasing productivity and streamlining the methods of harvesting Bartlett pears, cherries and tokay grapes.

Public Domain Image*

Muir devoted much of his time to the children’s upbringing and the industry of ranching. The couple had two children and lived in a big beautiful house that they were given by Louisa’s parents. Today, this home is the John Muir National Historic Site.

He made several trips to Alaska, visiting Glacier Bay and the numerous areas of the northwest in the 1880s. He visited Yellowstone, which had been named the world’s first national park in 1872, and Mt. Rainier, where he joined the sixth party to summit the 14,411 foot mountain.

Yet he lived in the world of men, and the brilliant author never seemed to find adequate time to produce the writings which were the original reason for his departure from Yosemite. There soon appeared a weakness in his spirit while pursuing the mundane life of standard society. His health began to fade and he began to fear the passing of time.

“I am losing precious days. I am degenerating into a machine for making money. I am learning nothing in this trivial world of men. I must break away and get out into the mountains to learn the news.”

John Muir

Fearing the rapid physical and spiritual deterioration that she witnessed in her husband, Lousia advised Muir to go replenish his soul in the wilderness.

She wrote in 1888:

“My dear John, A ranch that needs and takes the sacrifice of a noble life, or work, ought to be flung away beyond all reach and power for harm…

The Alaska book and the Yosemite book, dear John, must be written, and you need to be your own self, well and strong, to make them worthy of you.”

Louisa Wanda Stretzel

The following year, he was presented with the perfect opportunity to return to his favorite wilderness, when Robert Underwood Johnson, associate editor for Century Magazine requested that Muir escort him on a two-week camping trip to Yosemite. Having enjoyed but one brief visit to Nature’s grandest temple in eight long years, Muir jumped at the chance to return to the park, especially with a writer for an influential east-coast publication.

Muir’s Temple Desecrated

His return to the Valley was not the homecoming for which he would have hoped. The idea of absolute preservation that he espoused and for which he had advocated through long hours thoughtful writing where not on display. In their place he found an absolute degradation of the natural environment in a carnival-like atmosphere.

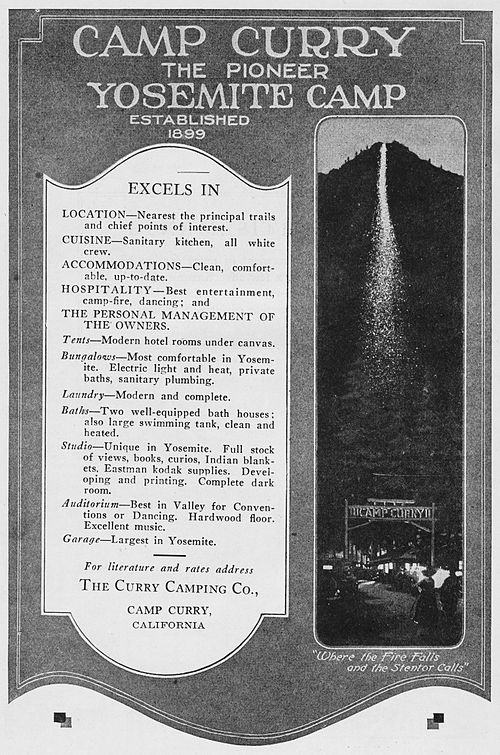

Tunnels had been carved through large ageless trees and live chickens were being tossed from clifftops in daily shows that left audiences aghast. Piles of garbage lay strewn about the valley floor and fuel-laced firefalls were a nightly display from Glacier Point. The flower-laced meadows of the high country lay near-barren due to constant overgrazing of the “hoofed locusts” that a younger Muir had once watched over in the magnificent summer of 1869.

Public Domain Image*

Not only was the scenic beauty of the mountain landscape at risk, Muir also warned that if the grazing of the high country continued unabated, the loss of soil would lead to significant problems downstream. Without the ability of the land to hold the moisture of winter storms, springtime melts would not only become destructive due to higher flows, but would become filled with silt and debris. Furthermore, the rapid drainage of such moisture would deplete water supplies that were needed for agricultural industry in the fertile Central Valley, to the west of the Sierra.

Muir was outraged and Johnson saw an opportunity to rekindle the naturalist’s fiery passion. He pressed Muir to begin a writing campaign aimed at protecting the high country surrounding Yosemite by making it a national park.

Muir’s New Mission

Much had changed since the adoption of Yellowstone as the nation’s first national park, some 17 years earlier. The idea of a national park had enjoyed unbridled success in the business of tourism. The railways that ushered visitors to and from its gates, were making an absolute killing from the constant masses that sought the park’s otherworldly scenery. Yosemite, as Johnson saw it, could benefit greatly from the same designation.

Upon his return to the family home, Muir undertook the mission to preserve Yosemite’s high country. A stream of editorials and articles were released from his hand, and his words found their way into an array of publications nationwide. Soon, there was a public outcry and Congress began receiving constant written requests for the preservation of a national shrine from all corners of the country.

Public Domain Image* John Muir, three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing front. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/93505505/>.

Muir’s writings immediately drew a backlash from California’s local constituents, who had interests in retaining control over their own lands. The Yosemite Park Commission retaliated against Muir, decrying him as a self-serving hypocrite. Articles were written designed to cast the naturalist as a fanatic and accused him of being the one who worked to destroy the famed Yosemite Valley.

Details were sensationalized regarding the construction of Hutchings’ sawmill, accusing Muir of attempting to create a commercial logging business in the valley. Stories circulated claiming that it was Muir who was squatting in the Yosemite Valley, resulting in his expulsion from the area in 1875, when in fact, that was Hutchings. Fake news is nothing new…

Meanwhile, Johnson’s writings drew recruits and his influential contacts began efforts of their own. It took little effort to entice the powerful interests of the railroad lobby to push for the idea of a new national park, in fact, several national parks, in the state of California.

The Railroad Influence

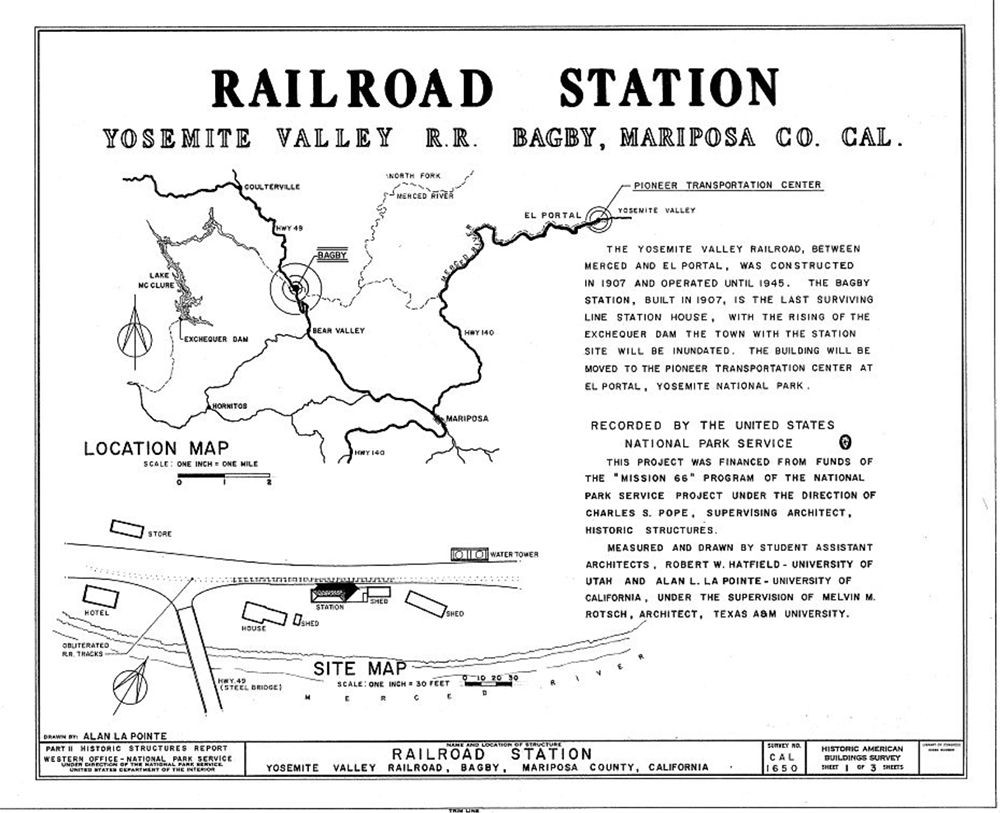

The railroad companies were quite happy to assist in the promotion of newly-romanticized destinations. It was abundantly clear from the experience of the Northern Pacific Railroad, which served Yellowstone, that tourism in such remote areas produced large profits for a few powerful captains of industry.

Public Domain Image*

The Southern Pacific Railroad was chartered in San Francisco in 1865, and originally connected San Francisco to San Diego. By the end of the 19th century, the company held lines that ran all the way to New Orleans and had arranged a lease with the Central Pacific Railroad, which provided track into Utah, as part of the First Transcontinental Railroad that was completed on May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah. The company also soon owned substantial land holdings throughout the state of California, in an effort to lay track throughout the state.

Even by the most conservative estimation, the Southern Pacific Railroad had become a major source of national economic and political influence in the late 19th century. Numerous names that are connected to the railway company are associated with efforts to preserve the lands that now constitute Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

The Southern Pacific Railroad had good reason to be in favor of the proposed national parks. Not only were there great profits to be made in the transportation of tourists into such remote areas, but there was also the issue of watershed protections. The railroad barons fully understood the importance of a continual clean water supply for the irrigation efforts in the fertile farmlands below. After all, their trains transported these goods to lucrative markets in the coastal cities of California.

Strange Bedfellows – Muir & the Railroad

The irony of the case that a powerful industry, was in fact, behooved by the opportunity to realize unbridled financial profits, to advance the idea of natural preservation, was not lost on John Muir. Realizing this truth, he and Robert Underwood Johnson presented their case for creating a national park in the Yosemite high country to the Southern Pacific Railroad executives.

Public Domain Image*

Not long after their plea to the railroad barons, pieces began to fall into place. On March 18,1890, Representative William Vandever of Los Angeles, presented a bill (H.R. 8350) in the U.S. Congress for the adoption of the country’s second national park.

This bill was not what Muir or Johnson had hoped for. It did not include any of the northern sections of the park, including Tenaya Lake and the Tuolumne River. Further, it included much of the original land grant to the state, thus the amount of new lands to be protected was essentially a mere 230 square miles.

Muir and Johnson expressed their disappointment. Johnson went so far as to testify on June 2, 1890 before the House Committee on Public Lands for the inclusion of more land. In reality however, these men did not hold the key to the passage of such legislation. The bill appeared dead…

A New National Park

Then miraculously, on September 29th, a substitute bill (H.R. 12187) that was in fact, the work of Daniel K. Zumwalt, a land agent for the Southern Pacific Railroad and a personal friend of Rep. Vandever, was introduced. This bill greatly enlarged the protected area surrounding Yosemite, offering up 900,000 acres, or nearly 1,500 square miles.

This bill somehow passed the House on the 29th, and passed through the Senate the very next day, September 30, with very little debate…

Public Domain Image*

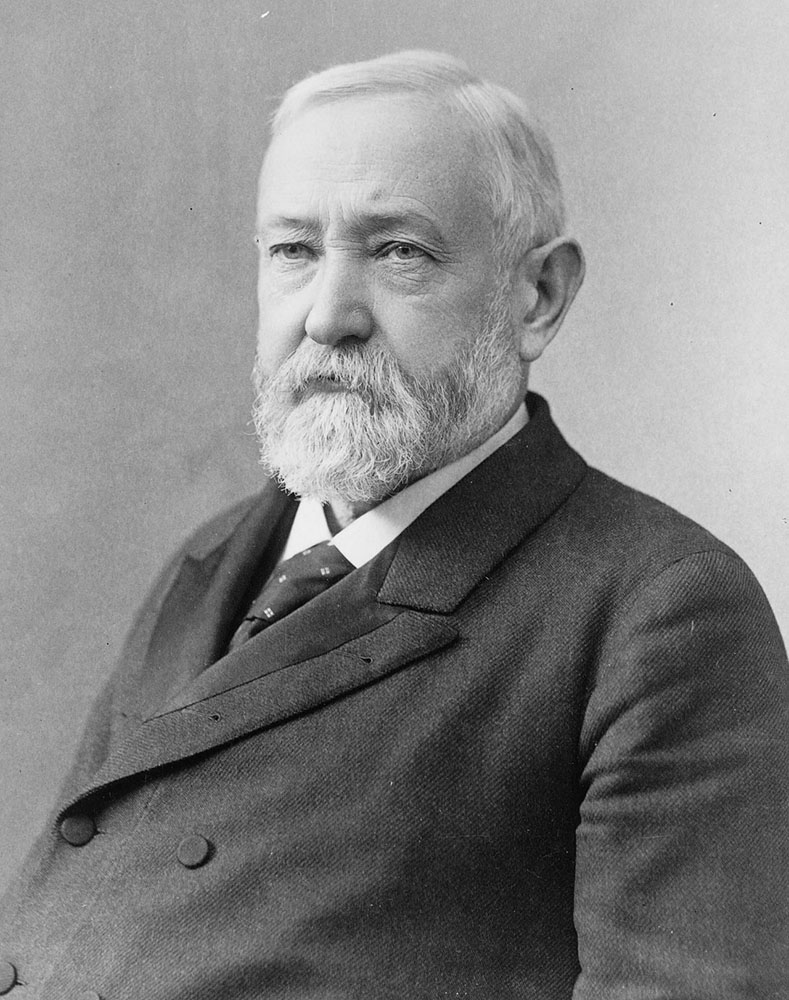

Two days later, on October 1, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed the bill into law. There were now four national parks, as Sequoia and Grant’s Grove had been authorized just the week before, with President Harrison signing the legislation for their creation on September 25, 1890.

Interestingly, Zumwalt’s substitute bill that was passed in place of the original, brazenly increased the size of Sequoia National Park, 200 miles to the south of Yosemite, a mere week after its creation.

The Soulless Southern Pacific

John Muir would be the victor here according to the history books. His efforts are permanently enshrined in the passage of these bills and the creation of all of these parks. His dedication, should by no means be underestimated or discounted.

However, the true magicians in the act were, of course, those with the necessary influence to push through whatever they wished. Those with real power.

Muir would later write:

“Even the soulless Southern Pacific R.R. Co., never counted on for anything good, helped nobly in pushing the bill for this park through Congress.”

John Muir

Public Domain Image*

Muir, by advancing his own natural preservation interests in coordination with the railroad’s interests in higher earnings, had found a clever way to manipulate the system. In doing so, the wandering Scotsman had set in motion a series of advances which would eventually lead to the establishment of numerous parks throughout the west.

Over the following decades, the railroads, sensing unlimited potential for earnings, were more than happy to lobby for additional parks, and to advance Muir’s goals, as they advanced their own..

Muir’s Unfinished Business

Even with the designation of the surrounding high country as a national park, Muir’s beloved Yosemite Valley still lay under the control of the local Yosemite Park Commission. Muir, celebrating hesitantly, resolved to continue toward the goal of including its acres under the national park umbrella.

With the passage of these bills and the creation of three new national parks, the nation now had the responsibility of protecting our new delicate temples of Nature. Obviously, there was no such agency as the National Park Service at this point, thus such duty fell to the United States Army.

Public Domain Image*

It was arranged that each spring, companies of troops stationed in Presidio, California would be dispatched to the three parks, where they would serve on mounted patrols in the mountains.

On May 19, 1891, Captain A. E. Wood of the United States Army reported with a company of troops to Wawona, where they established a headquarters from which they would oversee the newly created Yosemite National Park.

The task was not without hardship, and was at times a confounding affair, as park boundaries were continually called into question by sheepherders who sought the lush alpine meadows of the park’s high country. Captain Wood soon found that the most effective method by which the troops could prevent grazing in the park lands, was to separate the shepherd from his flock, making sure that the two parties exited the park in opposite directions.

Buffalo Soldiers

During the years of 1899, 1903 and 1904, many of the troops that were involved in the patrol of the park were units of the 9th Cavalry and the 24th Infantry. These were African-American soldiers, commonly referred to as “Buffalo Soldiers”, a name bestowed upon them originally by native Americans who remarked that their hair resembled that of a buffalo.

These patrols faced particular hardships when performing duties that required any display of authority from the black troops. White settlers of the late 19th century were not-at-all accustomed to recognizing African-Americans as figures of authority.

Many administrative duties at this time would often be difficult for a white soldier, as many locals already resented the federal boundaries that prevented their use of the land for ranching and grazing. Compound that with the fact that it was a black soldier commanding the cessation of such activity, and the recipe for a long day was immediately evident. Let’s just say these soldiers were required to practice diplomacy in the field, perhaps to a greater degree than that of many other soldiers of that time.

Public Domain Image*

The idea of conservation was new and untested at this point. Most of what constituted wilderness management during Yosemite’s early days was at best, trial and error.

For example, studies were undertaken by the troops to determine the effectiveness of fire suppression in Yosemite’s high country, with various opinions emerging over the following decades. Many preservationists, John Muir included, were in favor of suppressing fires, but the opinions of early commanders in charge of the park varied from year to year as these positions revolved each summer among Army officers.

Over the course of the following decade, the military troops that stood guard over our newly designated parks in California, and Yellowstone, proved largely effective in eliminating much of the destructive grazing, timber theft and poaching that took place within park boundaries.

“Blessings on Uncle Sam’s soldiers,” wrote Muir, “They have done their job well, and every pine tree is waving its arms for joy.”

While Muir’s stoke was high concerning the efforts of the military, his work was not done. The Valley remained under the control of the Yosemite Park Commission, whose members Muir referred to as “blundering, plundering, money-making vote-sellers.”

Slowly, public sentiment was turning against the California-controlled commission. But there still seemed little chance of returning the land to the control of the federal government. Muir contemplated the valley’s fate:

“As long as the management is in the hands of eight politicians appointed by the ever-changing Governor of California, there is but little hope.” he told Robert Underwood Johnson.

In 1892, with the upcoming battle for Yosemite Valley in his mind, Muir and 181 prominent preservation-minded Californians formed an organization they called the Sierra Club, with Muir as president. The purpose of the club was clear, to influence the public and the political sphere toward the conservation of the Sierra Nevada and Yosemite. Or as Muir himself said, “to do something for the wilderness and make the mountains glad.”

Roosevelt, Muir & Yosemite

Muir and his allies grew their numbers steadily over the following decade and began to gain influence in certain areas, although Yosemite Valley remained under local control. However, in 1903, Muir received word that his presence was requested in Yosemite.

“An influential man from Washington wants to make a trip into the Sierra with me,”he apologetically confided to an associate with whom he had planned a trip to Asia that would now be cancelled, “and I might be able to do some forest good in freely talking around the campfire.”

President Theodore Roosevelt was making his way around the American west, on a 14,000 mile tour through 25 states that took the rugged New York outdoorsman to Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and now, Yosemite. Here, he wanted to meet, camp and talk nature with the man that knew the place better than anyone.

“I do not want anyone with me but you,” the president had written Muir, “I want to drop politics absolutely… and just be out in the open with you.”

Muir, immediately sensing the rareness of the opportunity to have the ear of the most powerful man in the country, quickly dropped his plans, and made his way to meet the president for a most unique camping trip in his old stomping grounds.

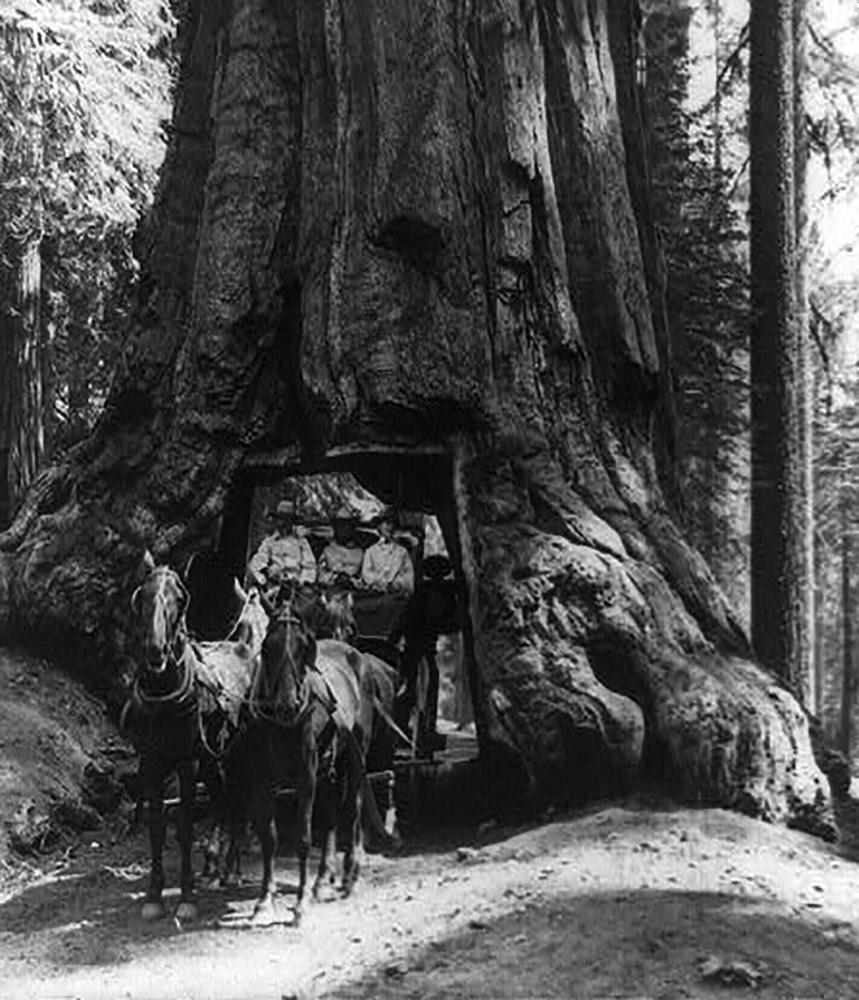

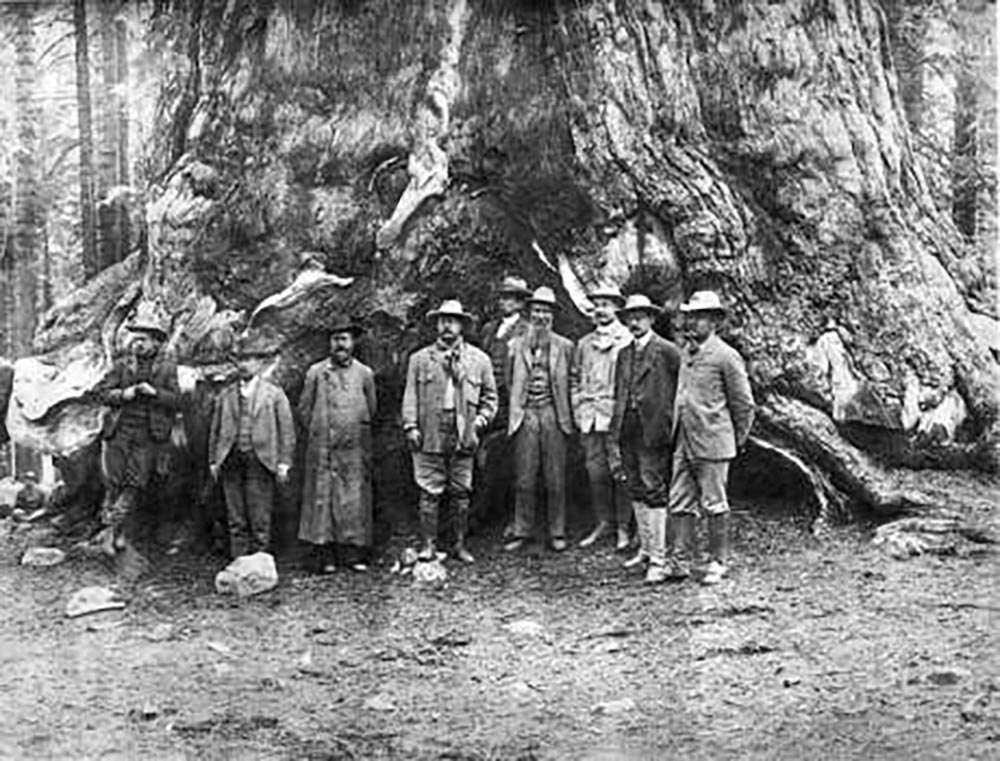

Public Domain Image*

He met the president’s entourage and the group made their way toward the Wawona entrance to the park. The group first stopped by the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, where photos were taken among the famous giants, and then they continued toward the Wawona Hotel, which had seen significant improvements since Galen Clark’s first days there in a rustic cabin.

Arrangements had been made for a lavish banquet and a formal dinner that evening at the hotel dining room in honor the visiting president. Unknown to those who had planned these events, however, was the fact that the president would not be attending, he had other plans.

Roosevelt Ditches His Entourage

After the completion of the customary preliminaries, greetings and photographs and such, that surround the visit of a dignitary such as a president, Roosevelt dismissed the troops that had escorted the party to the park, thanking them for their service, and calling out “God bess you”, as they rode away. Likewise, he dispatched the press and his staff to proceed to the Wawona hotel, some six miles away, where they fully expected to see him later for the evening’s events.

Upon the departure of his staff and the troops, Roosevelt and Muir, along with Army packer Jackie Alder, and park rangers Archie Leonard and Charles Leidig, who was acting camp chef for the group, set up camp under the giant Sequoia trees in the Mariposa Grove. The president’s bedding was laid under the Grizzly Giant, and consisted of some 40 thin army blankets.

Leidig prepared a meal of fried chicken and beefsteak, served on tin plates around a roaring campfire. The president and Muir spoke by the fire under the great trees, however, being tired from extensive travel, Roosevelt finished his dinner, drank several cups of black coffee and retired early that evening.

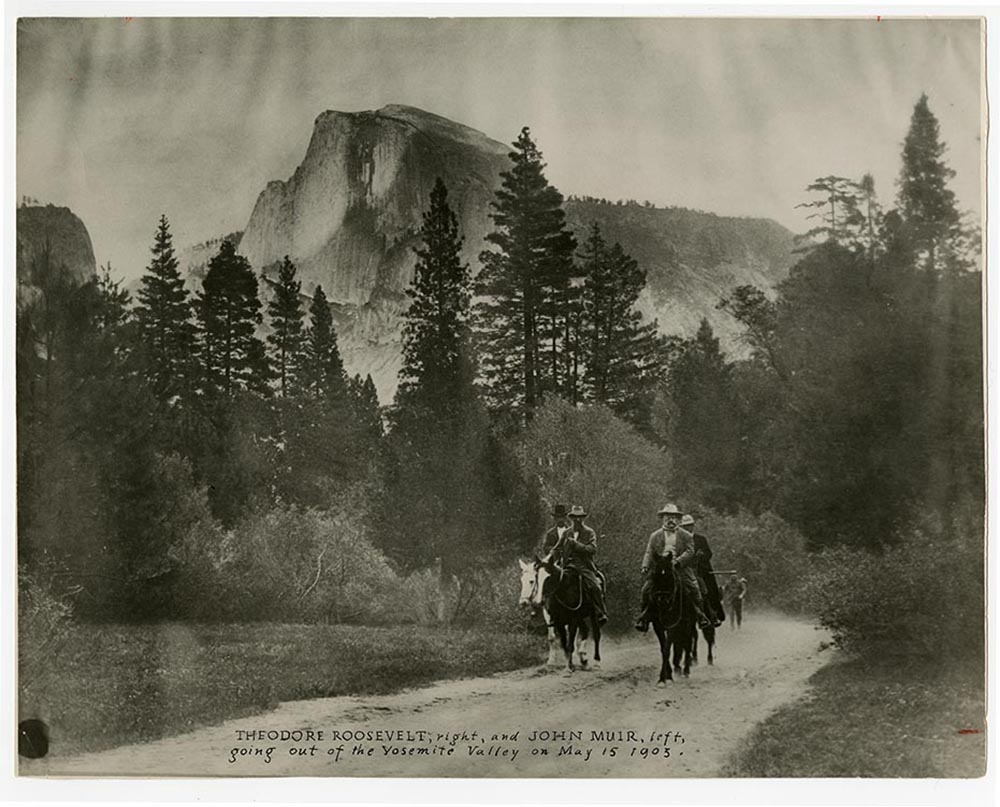

Public Domain Image*

The next morning, the men arose, broke camp and were on horses at 06:30. The president instructed Leidig to “outskirt and keep away from civilization.” The park ranger obliged, and the group rode along the Empire Meadows Trail, headed toward Sentinel Dome, near which they would camp the second night.

A full on Sierra Nevada snowstorm engulfed the group in Bridalveil Meadows, where they encountered 5 feet of snow. Each member of the party took turns in the lead, breaking a trail through the deep snow. At one point during his lead, the president and his horse became mired down in the snow, and Leidig had to dig them out with a log.

Muir suggested camping on the ridge of Sentinel Dome, however Leidig advocated continuing toward Glacier Point, where there was water, and less wind. The group decided on the latter, and continued toward the point.

A second night at camp found the president more relaxed and beginning to feel as if he were more in his element. A lifelong friendship of great importance began that evening, as Roosevelt and Muir spoke at length around the campfire late into the night. The two men discussed conservation efforts and Leidig reported that they began to devise strategies for the creation of other parks. Their escort also remarked that their dialogue was somewhat strained, “because both men wanted to do the talking”.

We Slept in a Snowstorm

The following morning, the party awoke to find their blankets covered by 5 inches of fresh snow. The assistants broke camp while the president shaved by the light of a great campfire, and soon joined Muir for prearranged pictures at Overhanging Rock. They then had a quick breakfast, and set out toward the Valley below, some 14 miles by horseback.

Public Domain Image*

In the Valley awaited throngs of visitors, who hearing of the president’s visit, had came to the park in hopes of catching a glimpse of the famous New York politician. The president, obviously annoyed at the crowds, nevertheless stopped to speak briefly, telling those gathered around:

“We slept in a snowstorm last night! This has been the grandest day of my life.”

The Governor of California and the members of the Yosemite Park Commission had arranged for fireworks and a number of festivities that evening to honor the president’s visit. However, once again, the president chose to skip such pretentious formalities, preferring instead to sit alone by the campfire with Muir for one more evening.

Shortly, following a quick visit to express his gratitude to artist Chris Jorgensen, who had offered his studio and home to the president during his visit, the party of five were off to Bridalveil Fall, where they would set up camp for Roosevelt’s last evening in the park.

Arriving at camp, the group was once again, surrounded by crowds, of which the president asked Leidig to disperse. After dismissing the masses, the guide returned to camp, and Roosevelt expressed his hunger and need for a nap.

“Charlie, I am hungry as hell,” the president said, “Cook any damn thing you wish. How long will it take?”

Leidig replied that it would take about 30 minutes, so the president took a nap on his bed of 40 blankets. He snored so loud that the camp chef could hear him above the sounds of the crackling campfire.

After dinner, Muir and the president strolled into the meadows of Yosemite Valley to enjoy the scenery. There they remained until well after dark. Upon their return to the camp, the two outdoorsmen once again talked for hours around the fire. The president told stories of his lion hunting trips, to which Muir responded with questions regarding the dignitary’s “boyish” need for killing things.

That Roosevelt did not become agitated with Muir’s inquiry regarding his infamous love for the sport of hunting, spoke to the great respect that he had gained for the naturalist. Likewise, Muir’s admiration for the president was evident as well.

“Camping with the President was a remarkable experience,” Muir later recounted,“I fairly fell in love with him”.

Roosevelt’s Contribution

Roosevelt’s actions over the next 5 years of his time in office would speak louder than any words he would utter concerning his time with the Sierra Club founder in the wilderness of Yosemite. Muir’s effort to “do some forest good in freely talking around the campfire” would pay off.

The outdoorsman president would go on to preserve more land than any other president in the nation’s history. Not until the Clinton administration of the 1990s, would any president preserve more land for public use. During his years in office, Roosevelt would set aside more than 230 million acres of public land and is personally responsible for the initial preservation of 23 units of what is now the national park service, 8 of which currently enjoy national park status.

Public Domain Image*

As the president departed Yosemite however, Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove, still lay under state control and were essentially, state holdings within a national park, whose management was an issue of growing contention.

Moreover, many of the specifics regarding park boundaries remained unsettled. The western region of the park had many areas that were a cobbled assortment of private and park land.

By the time Yosemite was established as a national park in 1890, numerous valid land patents had already been issued to settlers, lumbermen and miners in the area and many of these lay inside the boundaries of the newly designated park. These sections of land included prime stands of high-grade lumber, along with choice streams and shorelines that could be used for power generation by homesteaders. Early settlers were a wise lot, and the best lands went to the early arrivals.

Such holdings had in these cases, been acquired in good faith, unlike the contested claims of Hutchings and Lamon in the Yosemite Valley, thus settlers held legal claims to land that now lay within park boundaries. The park could either realign boundaries, or perhaps purchase these lands, but there was little money to do this in the federal budgets allotted to the park.

Logging in the Park?

The issue came to a head in 1903, when the Yosemite Lumber Company, which had obtained extensive holdings in the southwestern region of the park, began logging operations on its lands.

Nearly 60,000 acres of private holdings were estimated to be within the park boundary. Due to the number of such holdings along the western front of the park, a congressional commission decided the easiest solution was to simply reduce the park acreage along the western border, in order to eliminate these boundary disputes. This led to a February 1905 act by which Congress effectively reduced Yosemite’s size by some 430 square miles.

Photograph- E.M. Brickey / Public Domain Image*

Meanwhile, public sentiment and political winds were beginning to indicate that the state held grant to Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove was in its final throws.

Upon the founding of Yosemite as a national park in September of 1890, the U.S. Senate had asked the Secretary of the Interior to issue a report as to whether the lands of the Yosemite Grant had been “spoliated”, or otherwise diverted from the use stipulated by the grant. If so, what moves could be made to return the valley to its more natural state for public enjoyment.

Since no financial appropriations were assigned to the question, the Secretary mainly conducted his investigation through correspondence with respected individuals whom he thought to be aware of the details regarding the situation on the ground in Yosemite.

His investigation revealed that, generally speaking, there had been significant destruction of timber in the valley, in order to open views and to prepare land for the plow. Rare plants had been destroyed, and meadows had been fenced for pasture, while no pasture land had been set aside for the grazing of visitor’s horses or mules. Furthermore, there now existed a monopoly in the valley in the areas of lodging and transportation.

What to do with Fire?

The report also noted that fires had been allowed to burn, which had damaged trees and shrubs. This issue was one of some debate, as the general rule for the federally governed areas was to extinguish fire, while the practice of the Yosemite Commission, largely at the direction of Mills, who felt the fires beneficial to the land, was generally to let them burn unless they threatened structures or people.

(The fire debate would continue for decades to come, and only in the mid-late 20th century did the consensus of wildland management finally appear to agree that fires were indeed necessary in forest environments. Ironically, in the compilation of the first ten years of annual reports by the military commanders on the ground in Yosemite, the common conclusion was that instead of preventing and suppressing fires, they should be initiating a systematic burning of the forest to clear debris.)

1921 Camp Curry Advertisement / Public Domain Image*

Given the nature of the report, the Secretary concluded that, although it appeared that much of the activity on the valley floor was intended to augment minimal state funding of the park, the results of such activities were contrary to the original intent of the park.

A second report, dated November 15, 1892, found that the state commission operated solely with an eye to profit, and in a nature that was contrary to the preservation of the scenic and botanic wonders of the valley. This report recommended that the valley be returned to federal management under the protection of the surrounding Yosemite National Park.

It would be more than a decade before these reports, along with social and political pressure, in addition to the request of a major power broker, brought action regarding the recession of the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to federal oversight. The train was on the tracks, had left the station, and was gaining momentum…

Muir’s Sacred Temple

Speaking of trains, Muir at this point, was quite aware of the power of the railroad lobby. They had done him well in past dealings, magically facilitating the hurried passage of bills to create Yosemite, Sequoia and Grant’s Grove national parks.

The now-famous naturalist appealed directly to Edward H. Harriman, who controlled not only the Southern Pacific Railroad, but also the Union Pacific and Illinois Central lines. Harriman was a man of considerable influence in both California and national politics. Undoubtedly, his requests to politicians on all levels were taken into great consideration.

In April of 1906, Harriman wrote Muir:

“I will certainly do anything I can to help your Yosemite Recession Bill.”

Public Domain Image*

In March of 1905, California legislators passed an act that returned the state land grant to the United States, for admission into the greater Yosemite National Park. The Governor signed the bill, and the land was on its way to becoming part of the larger national park.

It would take more than a year to pass through the legal machine, but on June 11, 1906, President Roosevelt’s pen sealed the victory for John Muir and his Sierra Club. Yosemite Valley, and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, now were included under the title, Yosemite National Park.

Muir was ecstatic:

“Sound the timbrel,” he wrote a friend, “and let every Yosemite tree and stream rejoice!”

By this point, Muir was becoming a master of politics:

“I am now an experienced lobbyist; my political education is complete. Have attended Legislature, made speeches, explained, exhorted, persuaded every mother’s son of the legislators, newspaper reporters, and everybody else who would listen to me.

And now that the fight is finished and my education as a politician and lobbyists is finished, I am almost finished myself.”

Little did Muir know, that his final battle loomed on the horizon, one he would not win, despite his now great political acumen…. The future battle had power interests on both sides, and his railroad buddies would be sitting this one out…

Reflecting on the Early Park Effort

The effort to manage the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove by the state commission did not constitute a complete failure. The idea of such a park was entirely new. The balance between absolute preservation, and the desire to make such lands accessible to the public at large, while providing the minimal services necessary to sustain visitors’ needs, constitutes a great complication even today.

The embattled Yosemite Commission was asked to walk a political high-line, and failure was almost guaranteed from the outset. It is impossible to determine with any degree of certainty how the park would have looked had the commission not shelved the original recommendations of Olmsted. Nonetheless, the ideals expressed therein, were largely implemented in due time by future park service standards.

The lessons learned through the failures in management by the state commission provided important details regarding future decisions concerning commercial venues within park boundaries. Many of our busier parks still struggle to find balance between commerce and natural preservation today, and it is unlikely that such issues will be resolved any time soon.

Hetch Hetchy

1906 turned out to be a pivotal year for Yosemite, not all for the good. The park gained the admission of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa grove, but at the same time lost another 10,480 acres of land to private property in furtherance of the private land resolutions that were began the year before.

Secondly, and in the end, much more costly to the natural state of Yosemite, would be the eventual results of the San Francisco fire of that same year.

Pillsbury Picture Co. / Public Domain Image*

San Francisco was a rapidly growing city at the beginning of the 20th century, home to more than 400,000 people. City planners had long before set their sights on the Tuolumne River as a possible water source that could be dammed for a large reservoir.

The fact that the federal government now held exclusive rights to these lands only increased their attractiveness to those who held desire for their valuable water. This would mean that there were no messy contracts with various landowners, no issues with water rights, and now that grazing in the highlands was a thing of the past, there were no real pollutants in the water. In the end, damming one of these water sources would be the ideal solution to the growing water needs of a major metropolitan area.

In 1901, San Francisco mayor James D. Phelan, made a private application for reservoir sites and rights-of-way on the Tuolumne River and its tributaries and in the Hetch Hetchy Valley. The following year, he continued his applications for two reservoirs within Yosemite National Park, on the Tuolumne River.

These applications were denied by Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior under President Theodore Roosevelt, on the basis that the right-of-way passed over patented lands, on which the department lacked the right to grant passage.

Upon the denial, Phelan transferred his request for water rights to the city of San Francisco, flied another application, and second hearing was scheduled. Thus began a battle that would last for more than a decade.

Photographer-Isaiah West Taber / Public Domain Image*

In December of 1903, the Department of the Interior sent a letter to the General Land Office, formally denying the city’s application under the premise that the original act creating Yosemite National Park required the Secretary of the Interior to preserve the natural wonders of the park, and to maintain their “natural condition”. Such construction would eliminate that essence.

In the beginning, it appeared that the conservation argument would win out, and initially it did. Secretary Hitchcock’s finding that a dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley would violate the spirit of the bill which created the park, was essentially accurate.

However, in the spring of 1906, a major earthquake rocked the city of San Francisco. The severity of the quake brought hundreds of buildings to the ground, ignited countless fires and killed thousands. Much of the bayside city now lay in ashes, and those who buried their dead wanted a solution.

San Fransisco wants Water

Politicians and city planners immediately began to assert that had the city obtained an adequate water supply prior to the quake, they would have been prepared to fight the fires. While this view may have been inaccurate, it became popular, and the city overwhelmingly voted through a referendum calling for a dam at Hetch Hetchy.

Mayor Phelan moved to impugn Muir’s motives for his objection of the proposed dam. “John Muir loves the Sierras, and roams at large, and is hypersensitive on the subject of the invasion of ‘his’ territory,” he asserted. “The 400,000 people of San Francisco are suffering from bad water and ask Mr. Muir to cease his aesthetic quibbling.”

Muir fought back, writing his preservation-minded camping companion in April, 1908:

Dear Mr. President:

The few promoters of the present scheme…. all show forth the proud set of confidence that comes of a good, sound, substantial, irrefragable ignorance.

Hetch Hetchy…. is… one of the most sublime and beautiful and important features of the Park, and to dam and submerge it would be hardly less destructive and deplorable…. than would be the damming of Yosemite itself.

Faithfully and devotedly yours, John Muir

As the city struggled to rebuild following the devastation brought by the fires, newspapers, politicians and citizens rallied around the dam idea, which began to find support even among the ranks of the Sierra Club, as several prominent members began to call for the dam’s construction. Joining their calls was an influential east-coaster, with access to an important ear in back in Washington.

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot was chief of the newly created U.S. National Forest Service, and one of Theodore Roosevelt’s trusted allies. He was a Yale educated forester, whose philosophy regarding conservation differed from that of Muir. The latter supported complete preservation for the purpose of scenery, while Pinchot favored conservation of the natural environment through sustainable use and management.

Photographer – Benjamin Johnston – 1901 / Public Domain Image*

Pinchot threw his weight behind the dam idea, testifying before Congress that the project would represent “the greatest good for the greatest number”, while lobbying newly appointed Department of the Interior Secretary, James Garfield to support the construction. With their voices in Washington, and Muir in California, Roosevelt was reticent to oppose the dam. He replied to Muir’s plea for his aid in stopping the proposal:

My dear Mr. Muir:

Garfield and Pinchot are rather favorable to the Hetch Hetchy plan…. I have sent them your letter with a request for a report on it. I will do everything in my power to protect not only the Yosemite, which we have already protected, but other similar great natural beauties of this country; but you must remember that it is out of the question permanently to protect them unless we have a certain degree of friendliness toward them on the part of the people of the State in which they are situated…

[So] far everyone…. has been for it and I have been in the disagreeable position of seeming to interfere with the development of the State for the sake of keeping a valley, which apparently hardly anyone wanted to have kept, under national control.

How I do wish I were again with you camping out under those great sequoias or in the snow under the silver firs!

Theodore Roosevelt

Too many voices wanted the dam, the idea moved forward, and Roosevelt did little to stop it. However, his administration would end prior to the bill’s passage, and the controversial idea moved to the attention of newly elected President William Howard Taft.

President Taft visits John Muir in Yosemite

The ability to tour the American west by rail was a new possibility in the early 20th century, and everyone wanted to see the sights and sounds of this fabled land of mystery. President Taft took immediate advantage of the nation’s developing railway systems to access the once out-of-the-way national parks. He too, much to the chagrin of the San Francisco politicians, asked for Muir to be his guide in the now-famous Yosemite National Park.

Photographer – George W. Harris for Harris & Ewing / Public Domain Image*

Although the trip was in no way as rugged as that endured by Roosevelt, the beauty of Yosemite was not lost on Taft. He and Muir enjoyed one another’s company from the outset, and the famed naturalist referred to the 27th President as the “merriest man” he’d ever met.

Taft was a heavy man; in no way was he to be considered an athlete, more of an eater. It was noted by a local newspaper that Muir and the President’s stroll of a mile or so up and down a mountain road, left the large politician with “a splendid appetite for the picnic luncheon of fried chicken, potatoes, pie, fruit and jelly”….

Ah… the great outdoors!

Nevertheless, the two explored the park for three days, at one point, hiking the four mile trail from Glacier Point to the Yosemite Valley floor. It was reported that when they returned to their quarters, the President’s clothes were wringing wet, and he had to wait in his room while the only suit he’d brought on the trip was hung out to dry.

Taft would later refer to the days spent with his charming host in the Yosemite region as the most enjoyable times of his life. He would return to Washington, and he would oppose the construction of the dam at Hetch Hetchy. Muir once again, had prevailed in saving his Yosemite.

Victory was brief however, as the forces at work in California would press forward. Those who advocated the dam’s construction continued to lobby for Congressional support for the project. With the election of 1912, their chance would be realized.

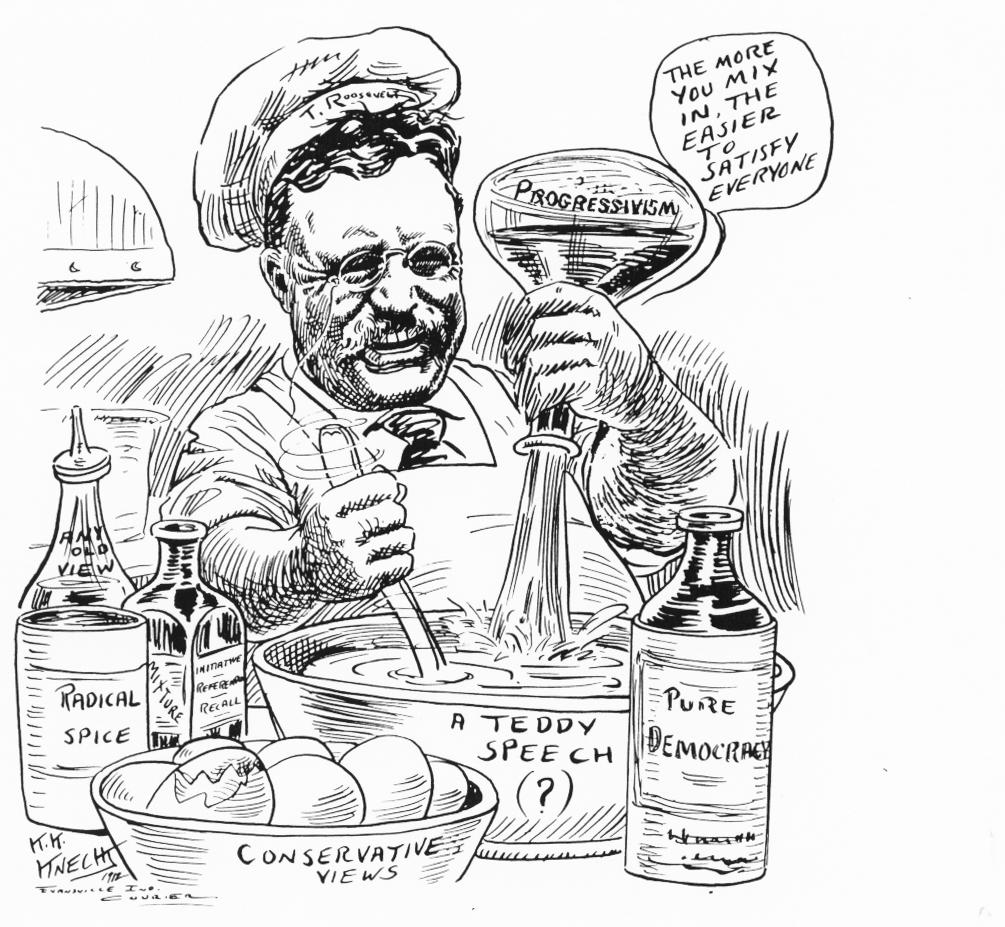

Bull Moose & Hetch Hetchy

Roosevelt had become displeased with the direction that Taft was moving in regard to a number of economic policies and grew eager to get back in the action. However, the former president proved unable to wrestle the reigns of power from Taft from within the Republican Party.

This led the former Roughrider to form his own party, the Progressive Party, commonly referred to as the Bull Moose Party. This pitted the former president against both Taft and the Democratic challenger, a former President of Princeton University, and a newcomer to politics named Woodrow Wilson.

Artist – Karl K. Knecht – Evansville Courier / Public Domain Image*

Roosevelt’s move proved costly for Yosemite. The Bull Moose and Republican parties split their vote, and handed an easy victory to Wilson and the Democrats. In a move that immediately signaled eminent doom for the preservation of the Hetch Hetchy Valley, Wilson chose Franklin K. Lane as his Secretary of Interior. Lane was the former attorney for the City of San Francisco.

They wasted no time in moving forward with legislation authorizing the proposed reservoir, with Wilson saying that he found the opponents’ arguments “not well-founded”. The newly elected President signed the Raker Act on December 19, 1913, creating the path for the construction of a dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park.

Muir’s Last Days

Muir never recovered from this loss. Despite the great victories won under his leadership in the battle to preserve a multitude of lands that we treasure today, the “unknown nobody” was distraught beyond consolation over the decision to flood the valley.

Posthumous portrait by Orlando Rouland – 1917 / Public Domain Image*

He retired to his home in Martinez, California and spent most of his remaining days in his library, trying to pound out a few more books before his time on this Earth expired.

John Muir would pass away the following year, on Christmas Eve of 1914…

Yosemite Today

As the decades passed, Olmsted’s prediction of a future Yosemite which welcomed millions of visitors proved to be correct. The park became a landmark of the preservation movement, and images of the Yosemite Valley are immediately recognizable to travelers worldwide. Today, the park stands as one of the classic national parks, and is a must visit for any aspiring Park Junkie.

As the park moves through the early 21st century, the issue of overcrowding stands as the main concern in the Valley, and a number of efforts are underway to relieve the pressure in the park’s most popular area.

It can only be hoped, that the powers that be consider the common traveler when determining the best coarse of action regarding access to the park’s most popular sites. Today, the park limits the number of hikers on Half Dome, requiring a permit to proceed to the cable section of the hike. While this may seem innocent enough, many once-in-a-lifetime visitors come and go from the park without setting foot on the infamous stone structure.

Numerous other restrictions are proposed, and while many of these intend to reduce impact, they also consequently reduce accessibility for many travelers. Perhaps society can determine a way by which we can provide access to these historic areas, and simultaneously reduce the human impact on our natural world, as well as deal with overcrowding in these sacred places.

Do we want our sacred parks to become a collection of reservation-only retreats that cancel any prospect of a spontaneous journey to our spiritual homes. To our sacred temples of nature?

These lands belong to us, the people, and were set aside with the express purpose of being for the benefit and enjoyment of the people, not just the people with a reservation…

Determining the best proposal to meet the visitation demands of the current day may be a difficult prospect. However, John Muir would certainly encourage the idea of a park without unnecessary restrictions. Park policies must be put in place that preserve the natural essence of nature’s most beautiful temple, while providing access to the public, because the land belongs to that very public. This is the purpose of the parks.

It is our duty as citizens to consider ways to alleviate the problems that plague our parks today. Think of possible solutions while you’re kicking back a cold one sometime.

Perhaps you yourself will be able to do some forest good one day…

Guide to Yosemite

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.