The history of Yellowstone is replete with colorful characters and wild adventure. Early explorers were considered crazy for even going into the region, and in the case of one of unfortunate wanderer, if he wasn’t crazy when he went in, he likely was when he came out.

Guide to Yellowstone

Early Visitors to Yellowstone

The early 1800s found Americans in a mood for expansion, and exploration of the largely unmapped lands of what would become the American West. The Lewis and Clark Expedition made history in the century’s first decade, by making their way through the vast expanse of land west of the Mississippi River, continuing all the way to the Pacific Ocean, and back.

The Corp of Discovery, as the group was known back in Washington DC, made their way just to the north of present day Yellowstone in 1806, where native tribes told them of a great lake to the south and a few rough French Fur Trappers described the area as the “Roche Jaune”, or the Stone Yellow.

Upon his return to St Louis, William Clark spoke to an Indian who held knowledge of the Yellowstone area. He told of an area where there was frequent “loud noise like thunder, which makes the earth Tremble“. Clark reported that the Indian told him that they “seldom go there because their children cannot sleep, and they Conceive it possessed of spirits, who were averse that men Should be near them“…

John Colter

One member of the Corp of Discovery was a 35-year-old mountain man by the name of John Colter. Born in the early 1770s in Virginia, Colter’s family soon relocated to Kentucky, where the young frontiersman became knowledgeable in the ways of hunting and woodsmanship.

A few years later, he would make his way to Pittsburg, where he encountered Meriwether Lewis, who was procuring supplies and vessels for the now-infamous western expedition. Lewis was impressed by Colter’s skills as a woodsman and offered him a position on with the Corp of Discovery, which would leave St. Louis in the coming months for western lands unknown.

Colter’s performance during the expedition was instrumental to the mission’s success. He was among the most skilled members of the team in most aspects of exploration. His name was one of the few which never appeared on the sick list, he was one of the most productive hunters, and he was respected as a honest tradesman by many native tribes with whom the Corp negotiated along their route to the sea.

After finding a successful route to the Pacific, the Corp returned eastward, which brought them to the Mandan Villages in present-day North Dakota. While here, Colter met a couple of frontiersman who were headed west in search of beaver pelts.

These men offered a partnership to Colter, who was intrigued by the opportunity to continue his exploration of the west’s vast unknown lands. Colter negotiated a honorable discharge from the Corp of Discovery, and headed back into the western mountains with his new business partners.

It wasn’t long before the partnership dissolved and Colter once again made his way east, where he met a man named Manuel Lisa, who was the founder of the Missouri Trading Company. Lisa was leading a party westward in hopes of establishing trade alliances and routes with Native American tribes who could provide valuable commodities and information about the surrounding mountainous areas.

Colter’s Hell

In October of 1807, Colter left Fort Raymond, which is located at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers, just east of Billings, Montana. He was directed by Lisa to to establish a trade network with the Crow Nation, who occupied much of the lands along the eastern region of today’s Yellowstone.

Colter traveled alone, and it is believed he made his way through the wilderness of present day Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, passing by geyser basins, steaming thermal pools and boiling mud pots while traversing the northwest shore of Yellowstone Lake and crossing the Yellowstone River near Tower Falls. The rugged mountain man endured hundreds of miles of harsh terrain, wildlife encounters, and mind-warping scenes in the dead of winter where frigid temperatures and -50° F nights are common.

Colter returned to Fort Raymond with tales that seemed like those of a madman. His stories of geysers which sent hot water and steam far into the air, bubbling pots of mud and crystal blue thermal pools that exuded boiling water were simply too much for the ears of those back in the common lands.

His tales of such fantastic sights led many of his cohorts to somewhat jokingly refer to the Greater Yellowstone region as “Colter’s Hell’, in reference to the unbelievable stories that their companion told upon his return from the otherworldly land to their west.

Colter went on to become famous for his time in Yellowstone and the surrounding area. He is widely acknowledged to be the first Euro-American to see the lands that currently make up the world’s first national park.

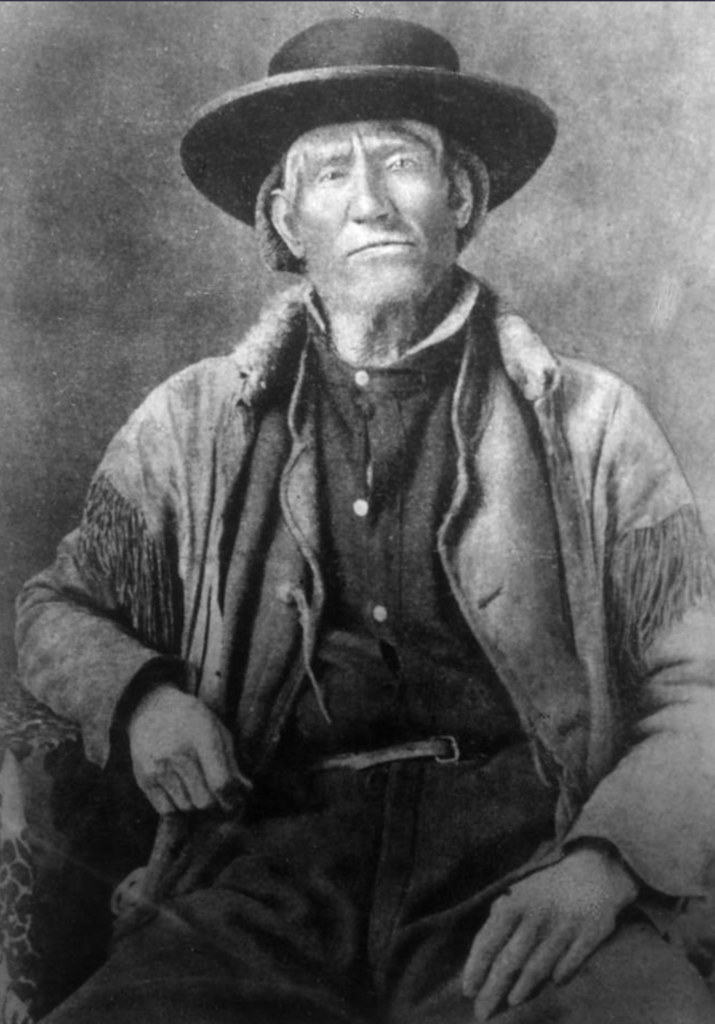

Jim Bridger – Tall Tales of Yellowstone

In 1804, about the time John Colter was heading westward with the Corp of Discovery, a child was born in Richmond, Virginia who would one day, like Colter, fascinate the civilized world with tales of this fabled land of bizarre thermal features and boiling mud. Although, his stories often held a wry comedic angle, and were usually slightly exaggerated and even bordered upon the absurd, with “petrified birds that sing petrified songs…”.

Jim Bridger found his way west as a child, with his family moving to St. Louis when he was about the age of 9. By age 13 however, the young Bridger was orphaned and he soon thereafter apprenticed to a blacksmith, for whom he worked until the age of 17 or 18, at which point he signed on to a fur trapping expedition on the upper Missouri River.

Bridger quickly gained the skills necessary to travel through the most rugged terrain in the west. His crossings of the Yellowstone country were numerous, and by the 1830s, he was widely regarded as the region’s foremost expert in topographical knowledge of the Yellowstone area’s rugged terrain. Perhaps more endearing to historians today was Bridger’s colorful descriptions of the oddities found in the mountains of the upper Yellowstone.

Bridger described the Yellowstone region as a “place where Hell bubbled up” and he described in vivid detail a world of petrified forests, carpeted with petrified grass, populated with petrified animals, complete with petrified birds that sang petrified songs.

His description of his favorite camping spot in Yellowstone detailed a “flat-faced mountain” which was so far away, that an echo from his yell in camp would not return for six hours. Legend has it that Bridger would yell out “time to get up” in the direction of the mountain before bed, and his echo would awaken him the next morning…

He also told of a lake in which a man could catch a fish, and reel it through a hot spring which would cook the fish, so that upon retrieval of one’s line, a freshly cooked trout could be enjoyed right from the waters in which it was caught. This could very well have been a reference to the Fishing Cone, at the West Thumb Geyser Basin… but who knows…

Despite such bizarre tales from a magical land, there is little debate that Bridger was the the foremost expert in when it came to the topography of the upper Yellowstone Ecosytem and the surrounding Rocky Mountains. His mental map of this region would lead to his position as a Major and chief guide for the Army at Fort Laramie in the 1860s.

Early Yellowstone Expeditions

In the late 1860s, as the nation recovered from a bloody Civil War, many set their sights on the American West. By the decade’s end, large swaths of wild western lands had been explored and mapped accordingly, but no such exploration had taken place in Yellowstone.

In 1862, a small group led by civil engineer and would-be gold seeker Walter D. DeLacy, traveled through the area and produced what is considered to be the first map of the lands of Yellowstone, yet the area’s overall topography remained a mystery. Several expeditions would change that in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

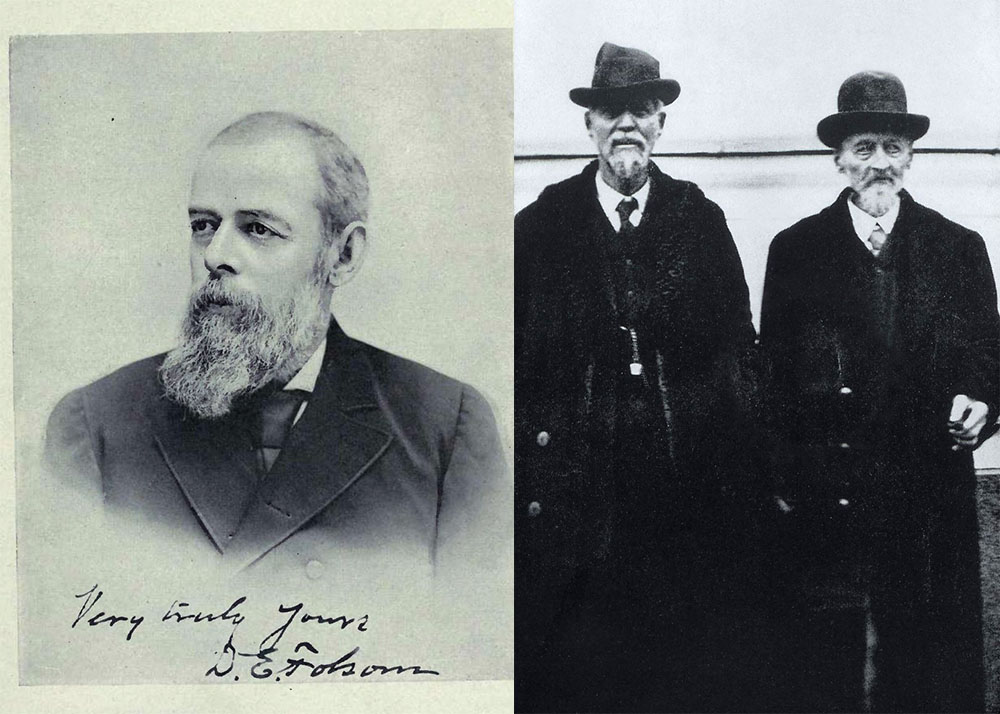

Folsom-Cook-Peterson Expedition

In 1869, the Folsom-Cook-Peterson Expedition traveled across what would just three years later, become the world’s first national park. The group departed Bozeman, Montana, despite warnings from friends that their journey was “the next thing to suicide” and made their way south along the divide that separates the Gallatin and Yellowstone rivers.

Public Domain Images*

They continued southward, passing by Tower Fall and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone before reaching Yellowstone Lake and the West Thumb Geyser Basin. From there, they visited Shoshone Lake and traveled along the Firehole River, subsequently exiting after a 36-day journey.

Although they were somewhat wary of publicizing what they had witnessed, the group would nevertheless attempt to publish articles detailing their trip. Magazines such as Harpers and Scribner’s Monthly declined to print the stories, which the magazine’s editors considered too unreliable to publish. One publication, Chicago’s Western Monthly did publish their tales in a story entitled “The Valley of the Upper Yellowstone”.

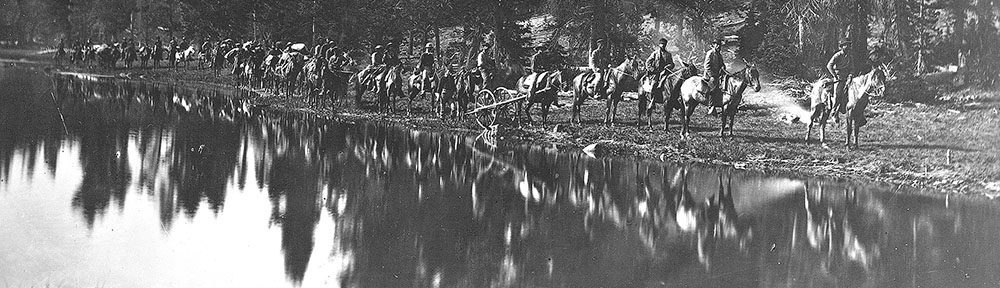

Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition

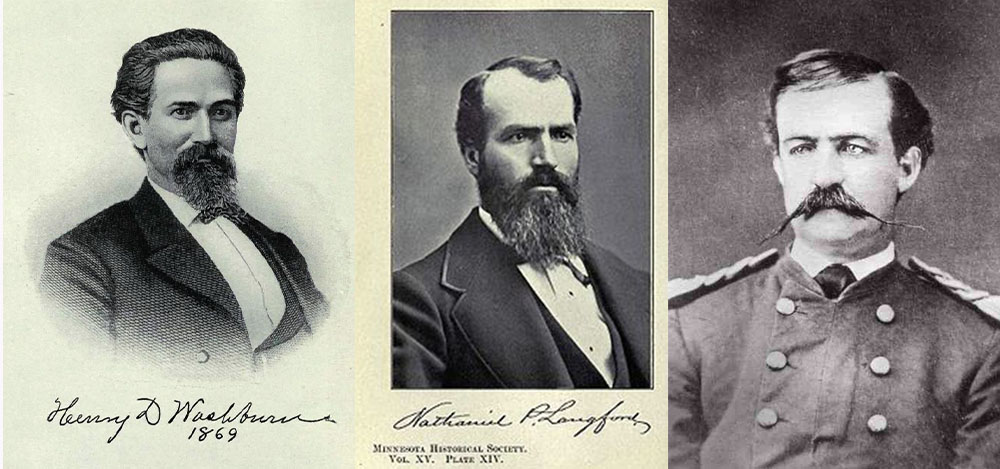

The following year, the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition set out with a party of seventeen men to explore the mysterious land. Led by Henry D. Washburn, the surveyor general of the Montana Territory, this group was motivated not only by curiosity, but also by the promise of big business.

Public Domain Images*

One prominent member of the expedition was Nathanial P. Langford, a Minnesota native who had became a well-connected businessman and tax collector in Montana. Langford had joined forces with Jay Cooke, of the Northern Pacific Railroad, who had quietly placed him on the railroad company payroll, in exchange for his support in securing passage of a second transcontinental railroad that would run through southern Montana.

As Langford and Cooke saw it, if the otherworldly wonders that were rumored to be true in Yellowstone actually existed, a railroad that would bring visitors to its gates was all but a certainty. A railroad that provided service to such an area promised good business for decades to come.

Public Domain Image*

It was not long before Langford and the expedition would have confirmation of the rumored landscape within Yellowstone. The group soon found themselves surrounded by boiling cauldrons and “diabolical” springs that reeked with fumes of “villainous odor”. Being some of the first white men to witness the bizarre land, they began to map and bestow upon the strange features names such as Brimstone Basin, Devil’s Den and Hell-Broth Springs.

Grand Canyon & Lake Yellowstone

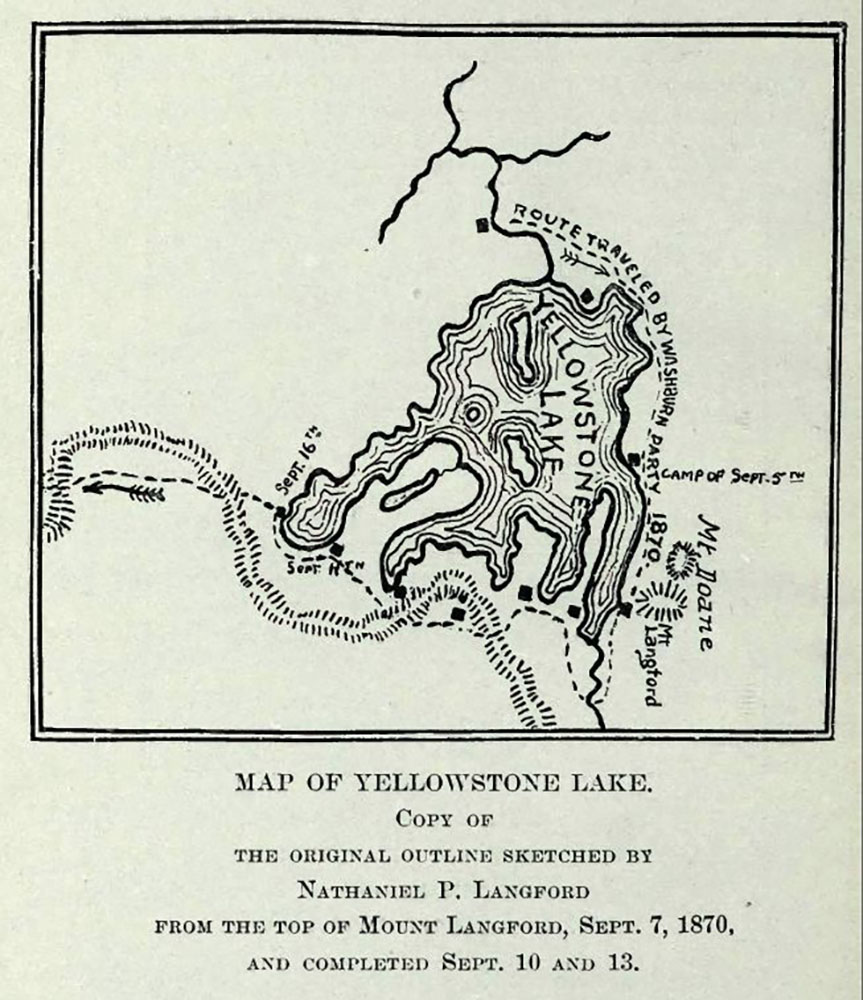

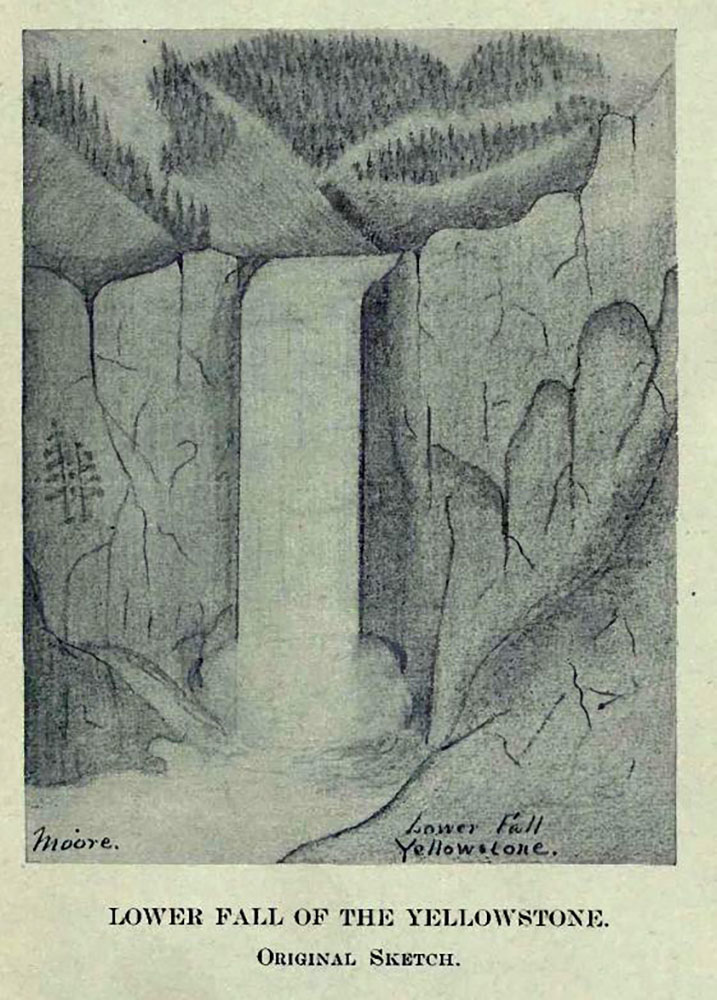

The group soon came upon the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and Upper and Lower Yellowstone Falls. They deemed the canyon nearly as deep as had been described some five decades earlier by Jim Bridger. Continuing to the south, lay Yellowstone Lake, which Langford described as “the most beautiful body of water in the world”.

Artist – Private Charles Moore / Public Domain Image*

Somewhere around Yellowstone Lake, a nearsighted member named Truman Everts became separated from the group. Search parties were sent out to search for the lost party member, to no avail. The remaining members of the expedition were intent on finding their lost comrade, however, a surprise September snowstorm buried them in two feet of snow. Supplies were dwindling, so the group was forced to move on toward the western mining town of Virginia City, leaving Everts to fend for himself.

Old Faithful

Having already witnessed what they considered the “greatest wonders on the continent”, they were soon stopped in awe once again.

“Judge, then, of our astonishment on entering this basin, to see at no great distance before us an immense body of a sparkling water, projected suddenly and with terrific force into the air to the height of over one hundred feet.

…. General Washburn has named [it] “Old Faithful,” because of the regularity of its eruptions, the intervals between which being from sixty to sixty-five minutes.”

Nathanial P. Langford

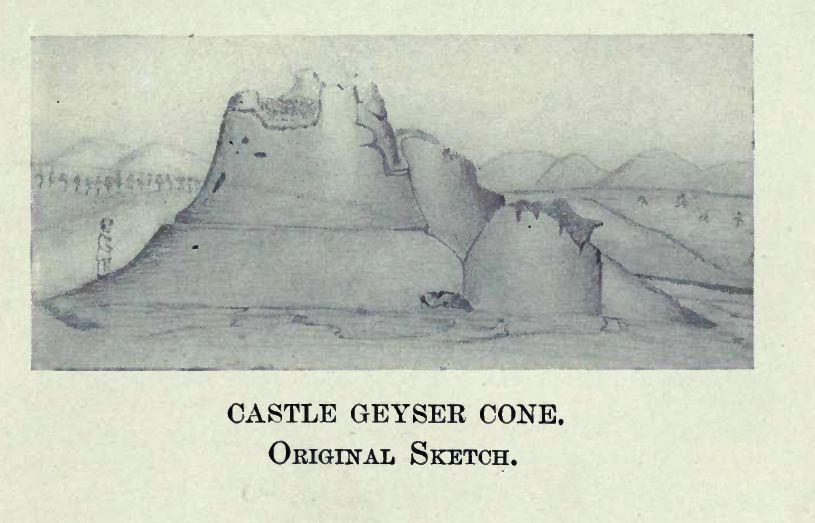

The party spent little time at what is today the Upper Geyer Basin, due to their lack of food and the shortening of the days that signified the onset of winter. Nevertheless, they named numerous features in the area, including the Beehive and the Castle, along with the Giant and the Giantess. They departed toward the west, following the Firehole River through a world of geothermal features unlike any other on Earth.

Artist – Private Charles Moore / Public Domain Image*

Upon their arrival in Virginia City, Montana, the group confirmed that the rumored story-land known as Yellowstone, was indeed real. Newspapers immediately printed the tales of their journey, verified tales of the under-worldly features such as boiling pots of mud and fountains of steaming water. While the confirmation of these bizarre formations fascinated readers, so did the predicament of the missing Truman Everts. What had become of him?

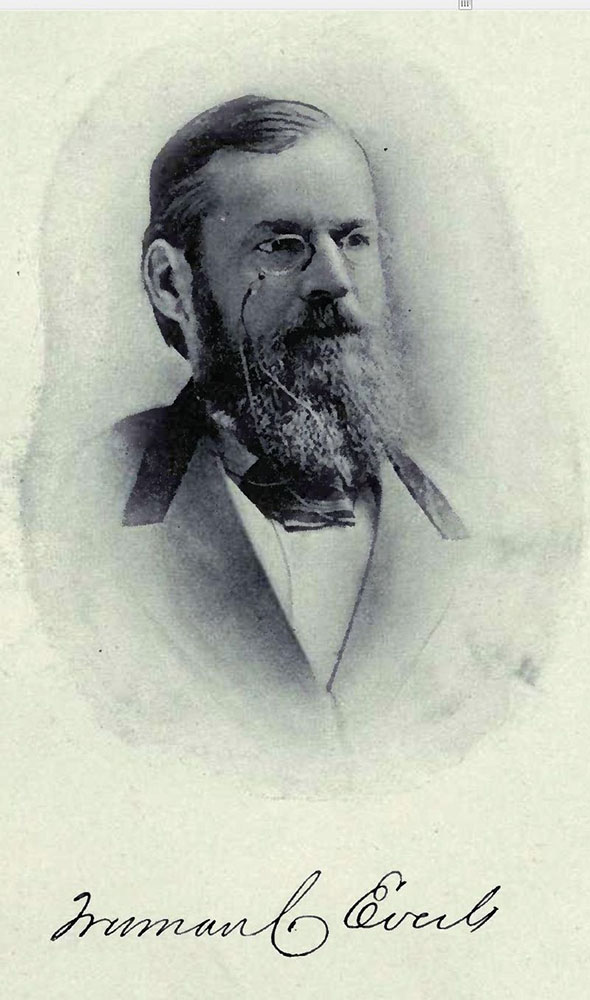

Truman Everts

Upon realizing that he had become separated from his group, Everts thought it a momentary inconvenience and settled in for a night alone in the wild. The next day however, the poor fellow lost his horse, which became frightened and ran away with nearly all of his belongings while he was dismounted. Stranded without his guns, fishing gear, blankets, food and matches in a cold dense forest, he soon realized the seriousness of the affair.

Public Domain Image*

“I realized I was lost. Then came a crushing sense of destitution. No food, no fire; no means to procure either; alone in an unexplored wilderness, one hundred and fifty miles from the nearest human abode, surrounded by wild beasts, and famishing with hunger.”

Truman Everts

He survived on the roots of the elk thistle plant. At one point, he managed to capture a small bird in his hands, and ate it. He became violently ill after ingesting raw minnows, spent cold nights without shelter and suffered frostbite. One evening, he was forced to sleep in a tree, corralled there by a mountain lion who fancied him a tasty meal.

He slept beside boiling springs in an effort to prevent freezing to death in the cold fall nights of a Yellowstone autumn, which often found him waking under a blanket of fresh snow. At one point, he was forced by a nearly week-long storm to remain in the company of the hot spring, fearing death if he were to depart.

“I was enveloped in a perpetual steam bath. At first, this was barely preferable to the storm, but I soon became accustomed to it, and before I left, though thoroughly parboiled, actually enjoyed it.”

Truman Everts

Everts had somehow maintained possession of an opera viewing glass, which contained a magnifying lens with which he was able to start a fire. He maintained a burning torch that he carried day and night. This, along with a fork that he had found at an abandoned campsite were his only tools, having somehow lost both his pocket and butcher knives.

Image from Scribner’s Monthly – Thirty Seven Days of Peril / Public Domain Image*

At one point while sleeping next to a scalding hot spring, he broke through the crust of the spring and suffered severe burns on his thigh. This, in addition to frost-bitten feet, prevented him from moving for seven days. He slowly realized that he was losing cognitive abilities. Hallucinations became apparent, and he heard voices that led him in ill-advised directions.

On October 16, as he neared absolute exhaustion and certain death, two trackers, spurred by a promised reward of $600, found an emaciated man crawling along a hillside. The men asked if he was Mr. Everts. “Yes”, he replied, “all that is left of him.” His body had withered away to a mere 50 pound skeleton.

Although he was near death when found, Everts recovered fully and went on to recount his unfortunate adventure in Scribner’s Monthly in an article entitled “Thirty-Seven Days of Peril.” Today, a 7,831 foot peak in the northwest corner of the park wears his name and the thistle which kept him alive is now commonly referred to as Everts thistle.

The Railroad Publicizes Yellowstone

The result of the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition was just as Langford and his friends at the Northern Pacific Railroad had hoped. National attention became focused on the newly explored wonderland.

The Montana businessman wrote glowing articles that were published nationwide describing the unbelievable landscape from which the party had just emerged. Funded by the Northern Pacific Railroad, he embarked upon a twenty-stop east coast lecture tour about the Yellowstone journey, titled “The Upper Waters of the Yellowstone River”.

One such lecture occurred in January of 1871, in Washington D.C. In the audience sat a man with a particular interest in the Yellowstone area. After listening to the first-hand descriptions of the spectacular scenery held in the upper regions of the strange land, he concluded that the area deserved a professionally led expedition. This expedition, he determined, would be conducted by expert surveyors who would record data and determine the scientific nature of Yellowstone.

The Hayden Expedition

That gentleman’s name was Ferdinand V. Hayden and he was in charge of the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. He had been part of at least two prior expeditions that had surveyed lands near Yellowstone in the late 1850s and had served on numerous other explorations throughout the Rocky Mountains in the 1860s, after serving as an Army surgeon in the Civil War. As head of a federal agency, he was able to secure significant funding from the federal government to aid in the journey.

Public Domain Image*

Educated in both geology and medicine, Hayden pursued any and all tasks with an eye for exactitude. This was clearly apparent in his assemblage of the team that would enter Yellowstone in the summer of 1871. Members of this group included two botanists, an entomologist, meteorologist, mineralogist, ornithologist, zoologist and a number of topographers that could map the area with scientific accuracy. The group also would include two artists that would bring the first images of Yellowstone to the world.

Thomas Moran

Thomas Moran was a young English-born painter who worked for Scribner’s. He had reworked and painted several rough sketches that were published along with Langford’s articles and had a desire to see the landscape for himself.

Public Domain Image*

He was not an outdoorsman however, and had never ridden a horse. His fragile nature required that a pillow was placed atop his saddle when riding on rugged terrain. Nevertheless, colorful descriptions and the rough sketches he was given by Langford were enough to stir wonder in the aspiring artist and he joined the expedition.

Henry Jackson

The second artist was a photographer named William Henry Jackson, a Civil War veteran who was much more at home in the wild than his painting partner. Following the war, he had sought adventure and headed west, working on a wagon train traveling the Oregon Trail.

Public Domain Image*

Jackson had settled in Omaha, Nebraska where he had opened a photography studio while working to photograph the building of the transcontinental railroad and to document the lives of the Plains Indians. His work for the Union Pacific Railroad led to his discovery by Hayden, who asked him to join the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871, otherwise known as the Yellowstone expedition.

Hayden Departs

The Hayden Expedition departed Ogden, Utah on June 8, 1871 and made their way north through what is today Idaho and into present day Montana, arriving at Fort Ellis, near Bozeman on July 10th. Here they resupplied and coordinated efforts with the U.S Army, who was tasked with providing a security detail that would escort the party into the Yellowstone region.

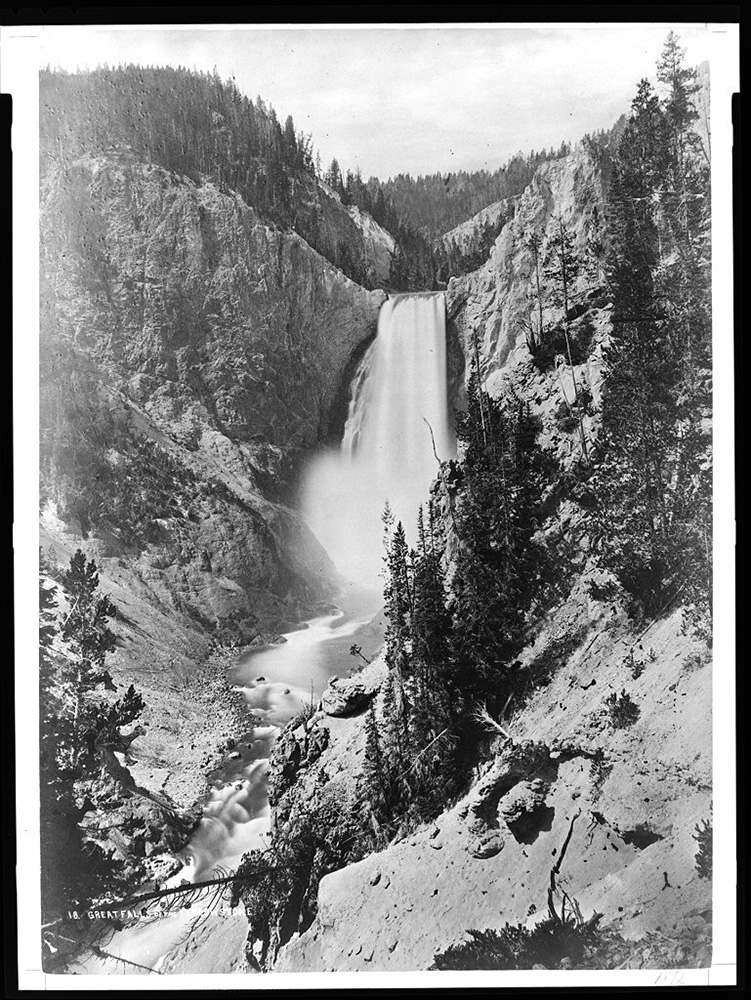

By July 21, the team had reached the Gardner River and Mammoth Hot Springs. Here they camped for two days before continuing to Tower Fall, where they moved southward around Mount Washburn, exploring the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. While moving southward along the Yellowstone River, they encountered Yellowstone Falls, where, W.H. Jackson took what are thought to be the first photographs of these popular falls.

Annie

Upon reaching Yellowstone Lake, several members of the party assembled a small watercraft that they had brought from Fort Ellis, and set out to explore the waters on a boat they named Annie. She would be the first boat known to have navigated the waters of Yellowstone Lake. Scientific measurements were taken concerning the depth of the lake, and exploration of the shoreline and its islands were documented.

Public Domain Image*

The group separated here, with some remaining at the lake, while others explored the Crater Hills Geysers and proceeded west toward the Madison River drainage. They reached the Firehole River and toiled several days to map the Lower, Midway and Upper Geyser Basins before departing for Shoshone Lake and Lost Lake. The team made their way back to Yellowstone Lake, pausing at the West Thumb Geyser Basin to document the lakeside hydrothermal activity before regrouping with the others.

Making their way along the southern shore of Yellowstone Lake, they veered off to explore the headwaters of the Yellowstone River, in what is today the southeastern section of the park. From here they headed north, along the eastern shore of the lake, and made their way to Turbid Lake, where they rested for a couple of days before departing for their return to the northern areas of Mammoth via the Lamar River, known then as the East Fork of the Yellowstone River. This led the group northward and they returned to Fort Ellis in early September.

A Successful Expedition

Many of the scientific studies and specimen gathered on the trip would provide valuable insight to the study of geology, botany and entomology, although the accurate mapping of the area was also of considerable value. Hayden’s lengthy report detailed nearly every aspect of the park that could be described by written word, and was arguably the most accurately compiled description of the territory that had ever been brought to the public.

Public Domain Image*

Perhaps even more important however, were the artistic representations that were made along the journey. For the first time in history, people from around the world could marvel at the wonders that for so long had been the subject of rumor and tall tales.

Thomas Moran and William H. Jackson became household names and their works became the subject of dreams that influenced those whose fascination rested in a world of adventure and wonder. The visions of these artists proved instrumental in the promotion of the park idea and so moved by these visual representations was Congress, that the legislative body paid $10,000 in 1872 for one of Moran’s paintings of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. Today, this work is found in the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

A Public Park Forever…

Back in Washington, Hayden worked to prepare his expedition report for Congress. During this time, he received a letter from a Northern Pacific lobbyist named A.B. Nettleton, who prompted Hayden to push for more than simple scientific recognition of the area. Nettleton wanted Hayden to present Congress with the suggestion that the area become a public park, to be preserved forever.

“Let Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever – just as it has reserved that far inferior wonder the Yosemite valley and big trees… If you approve this, would such a recommendation be appropriate in your official report?”

A.B. Nettleton – 1871

It is unknown what thought of this idea had been present in Hayden’s mind prior to this letter, given that the Northern Pacific Railroad had already benefitted his expedition by providing free rail travel to the area and had been indeed been the very impetus for young Thomas Moran’s inclusion on the journey.

Public Domain Image*

Hayden enthusiastically obliged, and joined forces with N.P. Langford and Jay Cooke of the Northern Pacific Railroad to promoting the idea of securing the landscape as a protected area, much the same as had been done with the Yosemite Grant in California in 1864.

However, there existed no state to take control of the area, and in the mind of many by this point, California was not doing such a great job of protecting the area it had been dispatched to care for in the first place. This idea would promote the preservation of the described area as a “national park”, administered not by a state or agency, but by the federal government.

Public Domain Image*

These men had plenty of political connections in Washington, and with the rising importance of the railroads, it seemed completely logical to promote an area that could drive business toward their developing infrastructure. It did not take long to get the ball rolling.

On December 18, 1871 bills were simultaneously introduced in the House and Senate to establish a national park at the headwaters of the Yellowstone River.

“Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the tract of land in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming, lying near the head-waters of the Yellowstone river….

is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart a a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people”

CHAP. XXIV. – Act to set apart a certain Tract of Land lying near the Head-waters of the Yellowstone River as a public Park.

March 1, 1872

With Langford, Hayden and Cooke steering the passage of this bill through their numerous connections who were blessed with political craftsmanship, the unique idea was approved by both bodies of Congress by comfortable margins, and arrived on the desk of President Ulysses S. Grant, who signed the park into existence on March 1, 1872.

These guys made it look easy… The world had its first national park…

Guide to Yellowstone

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.