The history of Bryce Canyon National Park is almost as colorful as the red and pinkish hoodoos that made it a national park. From the early visitors to this strange land, to the Mormon pioneers who later farmed surrounding lands, human history in this area is replete with fascinating lore and interesting characters.

Guide to Bryce Canyon

Native History of Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon National Park was never home to great numbers of people, as far as we can accurately determine today. Native Americans first occupied the Colorado Plateau some 12,000 years ago, but no evidence exists to suggest that they were ever present on the Paunsaugunt Plateau.

The Fremont and Ancestral Puebloans are known to have occupied areas near Bryce Canyon as early as 200 AD and are thought to have remained through 1200.

Paiute People in Bryce

While no great native settlements were known to have been constructed on or near the Paunsaugunt Plateau, the surrounding areas were occupied by the Paiute Indians since about 1200 AD Although no evidence exists to suggest long-term dwelling near the cliffs, the area was subject to seasonal hunting and gathering.

It is unclear today exactly how the natives viewed the unique structures found in their hunting ground. What is known however is that there was a somewhat mythical sense of reverence toward the towering objects.

In 1936, a Paiute elder named Indian Dick, who lived nearby on the Kaibab Plateau, spoke with a naturalist for the national park service. He told the tale that was passed down through his people regarding the land and its otherworldly features:

“Before there were humans, the Legend People, To-when-an-ung-wa, lived in that place. There were many of them. They were of many kinds – birds, animals, lizards and such things, but they looked like people. They were not people. They had power to make themselves look that way. For some reason the Legend People in that place were bad; they did something that was not good, perhaps a fight, perhaps some stole something….the tale is not clear at this point. Because they were bad, Coyote turned them all into rocks. You can see them in that place now all turned into rocks; some standing in rows, some sitting down, some holding onto others. You can see their faces, with paint on them just as they were before they became rocks. The name of that place is Angka-ku-wass-a-wits (red painted faces). This is the story the people tell.”

Indian Dick, 1936

Pioneer History

The Mormons arrived in the Great Salt Lake area in 1847 after trekking across the plains and the Rocky Mountains with hand carts and sheer willpower… At the time, this area was part of Mexico. The following year, the completion in 1848 of the Mexican-American War gave this vast new tract of land to the Untied States.

Mormons in Bryce Canyon

It didn’t take long for the industrious Mormons to settle any area of this region that had water. By the early 1860s, settlers from the church had been dispatched by Brigham Young to form a communities throughout southern Utah. Within a decade, the settlers were eying remote areas in the harsh canyon country east of Panguitch. One of these communities was to be located near the junction of the Paria River and Henrieville Creek, to the east of what is today Bryce Canyon National Park.

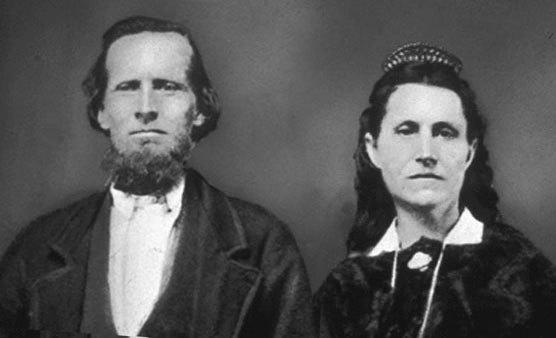

Ebenezer Bryce

A small number of families established the town of Clifton here in 1874. The following year a young couple by the name of Ebenezer and Mary Bryce arrived. Bryce was a 35-year-old shipbuilder from Scotland and his name would one-day be recognized the world over.

Bryce got right to work in the area. He built a road into the pink cliffs of his future namesake park in order to gain access to the rich timber that stood on the rim. He was a woodworker after all. He ran cattle in the area and was instrumental in the completion of a 7-mile irrigation ditch from Paria Creek that would supply the area with necessary water. Folks began to refer to the rugged land near the edge of the cliffs as Bryce’s Canyon.

Bryce and his wife left the area in 1880 for the warmer climate of what would one day become known as Bryce, Arizona, but the name of Bryce’s Canyon stuck to this strange collection of standing hoodoos and in 1928, his name was applied to what was announced as Bryce Canyon National Park.

Bryce left few, if any, records detailing his awe or wonder considering the area that today bears his name. The most widely recognized statement that he is known to have made concerning the area must be considered an absolute fact…

“It is a hell of a place to lose a cow”…

Ebenezer Bryce

Park Creation

The intricate formations found throughout southern Utah were being brought to the attention of the American people in the early 1920s. Zion National Park had been named in 1919, after gaining national monument status in 1909. At the southern end of the Grand Staircase, the Grand Canyon was also named a national park in 1919.

The National Park Service was newly formed. An ambitious businessman named Stephen Mather took a seat as director of the agency in 1916. The energetic new park service director had his eye on new areas that would make exciting additions to the nation’s growing collection of incredible landscapes.

J. W. Humphrey

In July of 1915, J.W. Humphrey, a U.S. Forest Service supervisor, had been transferred to a station in Panguitch, Utah. With his location just less than 20 miles west of Bryce, Humphrey soon heard about the amazing landscape on the eastern edge of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. He soon took a trip to the area and was immediately struck by its grandeur.

“You can perhaps imagine my surprise at the indescribable beauty that greeted us, and it was sundown before I could be dragged from the canyon view. You may be sure that I went back the next morning to see the canyon once more, and to plan in my mind how this attraction could be made accessible to the public.”

J.W. Humphrey

Humphrey took the matter into his own hands and sent photographs to Forest Service and Union Pacific Railroad officials. Word spread about the small plateau in Utah and it created a stir… In 1916, Humphrey was successful in securing an appropriation of $50 in order to improve the road and to make it accessible to the growing number of automobiles rolling around America.

Stephen Mather Visits Bryce

It was not long before Stephen Mather, who was touring southern Utah in hopes of making Zion a national park, was brought to Bryce. The guide that brought him to the rim’s edge required that he be blindfolded until he got to the viewpoint. Upon removal of the cloth, he became excited and exclaimed that it was “exquisite” and “marvelous”and that there was “nothing like it anywhere!” Mather began immediately to press for its inclusion in Utah and Washington D.C. The history of Bryce Canyon would change forever.

Photographer: Marian Albright Schenk – Public Domain Image

By 1919, the area was on the map and became a popular stop for tourists touring from Salt Lake City. Sensing a business opportunity, Ruby and Minnie Syrett placed tents near Sunset Point and began to supply meals for their guests. In 1920, they constructed a lodge and a few cabins to house guests and built an outdoor dance floor. Business was good.

The Railroad Finds Bryce

By 1923, the Union Pacific Railroad had taken note of the opportunity that was growing on the plateau. The railroad company bought the land, buildings and water rights from the Syretts. Seeking to capitalize on their new purchase, Union Pacific hired renowned architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood to design a lodge that would be built near Sunset Point. The main lodge was finished by the spring of 1925 and the final additions were completed by 1927. The adjoining cabins were added by 1929.

Bryce Becomes a National Park

The growing hype about Bryce made its way to Washington and on June 8, 1923, President Warren G. Harding named it a national monument. The following year, a bill passed through the halls of Congress to establish Utah National Park and on February 25, 1928, the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon were officially proclaimed Bryce Canyon National Park.

Guide to Bryce Canyon

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.