The history of Zion National Park closely parallels the history of the national park service. The park service was implemented in 1916 to provide some structure to the fledgling number of parks being created during the early 20th century. As we’ll learn shortly, Zion’s adoption as a national park in 1919 was the brainchild of the same Utah Senator that had three years earlier introduced the bill to create the body that governs it – the National Park Service.

Guide to Zion

Early People

The Zion area has been home to inhabitants for at least 8,000 years, although most of these were nomadic peoples of hunter gatherer cultures. About 2,000 years ago, groups began cultivating crops, which allowed more permanent settlements of the Fremont Culture and the Ancestral Puebloans, sometimes referred to as the Anasazi. Archeologists often find their stone knives, drills, and pottery in small cliff dwellings in the park’s remote canyons.

Somewhere around the 14th century, these people left the region, and were soon replaced by the Paiute and Ute Indians. The later residents used the area on a seasonal basis, and cultivated crops of corn and squash next to the river.

Europeans Visit Zion

The first Europeans arrived in the late 1700s. Francisco Dominguez and Father Escalante passed through the region in 1776 while searching for an overland route to California from Sante Fe, New Mexico. Their party was turned back near the Sierra Nevada Mountains. On their return home, the group passed by the site of the modern day Kolob Canyons, undoubtedly sending scouts to observe the surrounding scenery.

Mormon Pioneers Farm in Zion

Mormon pioneers arrived in the 1850s, when missionary Nephi Johnson entered the main canyon in 1858 with a Paiute guide. He returned word to church leaders that the area was favorable for agricultural pursuits and in 1861, Mormon saint Joseph Black established a small farm in what is today Zion Canyon.

Soon came Isaac Behunin, who built a one-room log cabin near the site of the modern-day Zion Lodge. Here he farmed tobacco, sugar cane and various fruit trees. Behunin believed the canyon possessed a spiritual essence, and bestowed the name Zion Canyon upon this place of peace, refuge and sanctuary.

John Wesley Powell

Zion Canyon remained unknown to the outside world at this point, but that would all change in the coming decades. In 1869, John Wesley Powell’s expedition entered the Zion Canyon vicinity, following their first decent of the nearby Colorado River, through the Grand Canyon.

Public Domain Image*

The one-armed Civil War veteran returned with a geologist and an artist three years later to explore the area. Powell named Zion Canyon “Mukuntuweap”, a Paiute word meaning “straight canyon”, in reference to its high, vertical walls.

Fredrick Dellenbaugh

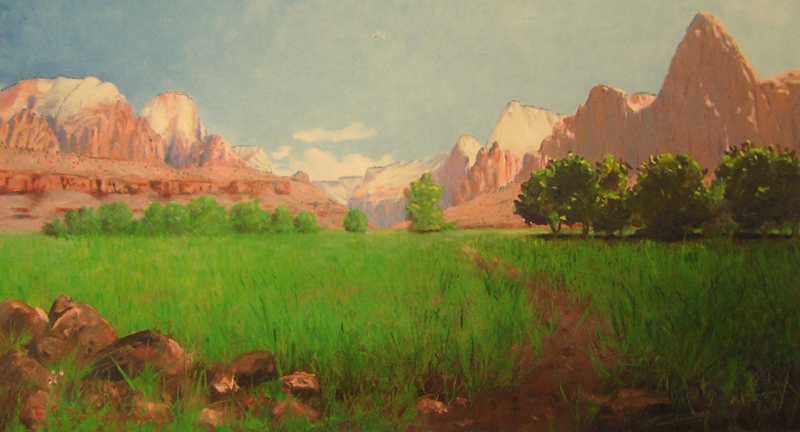

Artist Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, a seventeen-year-old Ohio native, served as assistant cartographer on Powell’s 1871-1873 Colorado River expedition. The group passed through the Zion area on their exit from the Grand Canyon and witnessed the splendor of southern Utah. Zion Canyon left quite an impression on the young painter, and he returned in 1903 to spend his summer painting its majestic red cliffs.

His images introduced the remote area to the public when they were exhibited at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. Audiences were often aghast, finding it impossible to believe such a place existed. Later that year, Dellenbaugh would write an article titled “A New Valley of Wonders” that was published in Scribner’s Magazine, bringing light notoriety to the area.

Mukuntuweap National Monument

These publications, along with other reports, reached the desk of President William Howard Taft. On July 31, 1909, the president used the Antiquities Act to designate the canyon as Mukuntuweap National Monument.

Mormon settlers in the area were not happy with the historical Indian name and many took this action as a direct insult to the LDS church. Other outsiders found it hard to pronounce and its significance was lost on the public at large.

The National Park Service was created in 1916 in an effort to create an effective management strategy for the growing number of national parks.

After fielding nearly a decade’s worth of complaints and public outcry from local Mormons, acting NPS director Horace Albright had heard enough. In early 1918, he drew up a proclamation to change the name to Zion National Monument. Included in his resolution was a proposal to increase the size of the monument. His motions were approved and Zion’s size increased from 15,840 acres to 76,800 acres.

Utah’s First National Park

The following year, Utah Senator Reed Smoot introduced a bill that would designate the area as a national park. With the stroke of President Woodrow Wilson’s pen, the monument was named Zion National Park on November 19, 1919. Interestingly, Senator Smoot was also instrumental in crafting the bill to create the National Park Service, just three years before.

Despite its position as a national park, the area was still extremely removed and difficult to access. This was all about to change however, because Senator Smoot had already helped secure appropriations to construct the first road into the canyon in 1917.

The roaring 20s saw significant development in Zion Canyon, and increased efforts to bring the world to Utah’s first national park.

The Railroad Influence in Zion

In 1923, the Union Pacific Railroad completed a railway line from Lund, Nevada to Cedar City, Utah. The Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific, housed the guests at its Hotel El Escalante. Guests were then transported to Zion via a fleet of 11-passenger convertible cars. Park junkies may recognize these automobiles, as they were similar to those still used today in Glacier National Park.

The Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, soon acquired the Wylie Camp. This was a small tent camp in Zion Canyon, which was desired for nothing more than its location. The developers immediately began construction of 46 small guest cabins. Construction also began on the Zion Lodge, which was designed with a “rustic style” by architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood.

This effort used lumber that was lowered into the canyon via cable from more than 2,000 feet above. A local man named David Flanigan constructed the “cable works” in 1900, to provide Ponderosa Pine from Zion’s eastern mesa. The remains of this structure can be seen today, atop Cable Mountain, just opposite Angel’s Landing to the east. The cable rigging structure can be accessed by the East Rim Trail. The view from here is a park junkie favorite among all the trails in the entire park.

Advertising campaigns touted Zion’s spectacular scenery in popular east-coast publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and Literary Digest.

Zion’s Record Attendance

Such tactics still work to draw guests to this natural phenomenon today. The park steadily deals with increasing guest numbers and in 2000, the park implemented a mandatory shuttle service in order to decrease congestion in Zion Canyon.

The State of Utah released its Mighty Five campaign in recent years to draw guests to its national parks. This effort has resulted in record attendance in Zion. The park was the third most-visited in the national park system, with 4.6 million visitors in 2017 and the second most-visited with over 5 million in 2021.

As Zion faces the complexities of an ever-increasing popularity in the 21st century, struggles to manage the crowds will become the primary challenge faced by the NPS.

Guide to Zion

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.