It has been little more than a century since the dawn of tourism at the Grand Canyon. Yet evidence suggests it is likely that mankind has marveled at the canyon’s overwhelming scale for more than 10,000 years.

We have little evidence of the personalities of the original visitors and inhabitants. However, the past 170 years have witnessed a string of colorful individuals. Such characters have contributed to a colorful history of Grand Canyon National Park.

Guide to Grand Canyon

Early People of the Grand Canyon

Little is known of the earliest visitors to the Grand Canyon. Such folk left very little trace of their time here. There are no structures or petroglyphs and only rare signs that even hint at their presence. Only two known sites within the park remain today that indicates a Paleo-Indian presence. These date to 11,500 – 8,500 Before Present (BP).

The oldest is a piece of chert (sedimentary rock) that was used for a spear tip. This find dates to nearly 13,000 years ago. It appears that this stone tool was transported by an ancient hunter from an area in New Mexico, later to be unearthed on the South Rim.

Another piece of chert was found that dates to 10,000 years ago. This artifact was found near the river, in the heart of the canyon. Was this point dropped here by a hunter that ventured into the depths of the canyon? Or did it simply wash down from above….?

The descendants of the Paleo-Indians, known as the Archaic, faced a constantly evolving climate in the southwest. These transient people moved with the seasons, hunting small game. They slowly perfected techniques for constructing tools that aided their mobile lifestyle. Chipped stone tools for processing plants, such as the metate, were developed as well as atlatls for throwing spears. Numerous Archaic sites exist within the Grand Canyon.

Beginning around 3500 B.P. the lives of these early people gradually became more sedentary thanks to the implementation of plant cultivation. The growth of edible corn, squash and beans was dependent upon water and thus primitive agricultural pursuits were centered near water sources, such as rivers. These practices advanced slowly however, and it would be some time before their adoption of a semi-sedentary lifestyle.

More than 500 small animal-shaped figurines that were constructed from willow branches were discovered in a Red Wall limestone cave within the Grand Canyon in 1933. Radiocarbon dating indicates that these small figurines are some 2,000-4,000 years old. Several of these artifacts are today displayed in the National Park Museum Collection at the South Rim.

Ancestral Puebloans in the Grand Canyon

The rising use of agriculture allowed the area’s population to expand. A group known today as the Ancestral Puebloans took control of the region beginning around AD 500. These people built impressive structures, such as impressive granaries and cliff dwellings. Some of these ruins still exist in the park today.

The Puebloans departed in the 1200s, for reasons that remain largely unknown. Many scientists believe climate change, perhaps a long, severe drought, drove them from a relatively comfortable existence in the desert southwest. They would eventually be replaced by other tribes. Afterward, tribes such as the Hualipai and the Havasupai would inhabit the canyon. These tribes continue to live in the Grand Canyon region today.

Early Grand Canyon Explorers

Spanish troops seeking gold and silver were the first European visitors to the area. Soldiers searching for the Seven Cities of Cibola traveled north from Mexico City in 1540, led by García López de Cárdenas. Arriving at the Hopi Mesas, east of the Grand Canyon after a six month expedition the Spanish found ostensible assistance from the Hopi Indians.

The Spanish were hoping to find a river that would provide a waterway with a route to the Gulf of California. Hopi leaders instructed their men to send the visiting soldiers on a “wild-goose-chase” and to give them no relevant information.

The Hopi led the Spanish on a three week journey that culminated at the edge of the Grand Canyon. Cárdenas ordered a few of his infantry men to descend to the river and to assess its navigable possibility. The men advanced no more than 1,500 feet before thirst and the realization that the river was much larger than originally assumed turned them back toward the top. It was clear, no ships would be taking this course to the Gulf of California.

Cárdenas and his men searched three more days for a possible route to the river, but the Hopi had led them to a point which offered no access to the land below. Concluding that this was an impenetrable wasteland, Cárdenas reported that this area was not navigable and his commander abandoned further exploration of the area. The Grand Canyon would not receive notable attention for the following 235 years.

“The Great Unknown”

By the 1850s, there were few blank spaces on the map of the western United States. Following the mad dash to the west created by the gold rush in 1849, many areas of the west were already home to small settlements and very few were left unexplored.

The Grand Canyon stood as the remaining unknown area of the southwest, and the federal government was in search of valuable trade routes through the southwest. The remote reaches of what was commonly termed “The Great Unknown” were to be mapped despite the apparent difficulty. Uncle Sam would foot the bill.

The adventurous task fell to the US Army Corps of Topographical Engineers.

Joseph Christmas Ives

Army Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives was born in New York on Christmas Day in 1829. Following an education at Bowdoin College he attended the US Military Academy where he graduated in 1852. Soon after an appointment to the Army Corp of Topographical Engineers, he found himself headed to explore the west with a Pacific Railroad survey in search of a route for the proposed continental railroad.

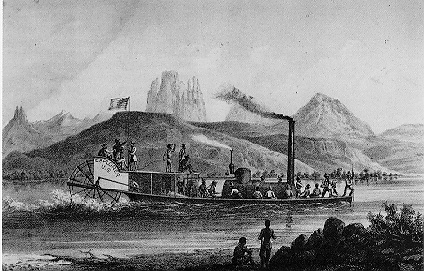

While in the region, Ives was given command of an expedition to map an unknown area of the Colorado River. The Army Lieutenant was to navigate upriver in a 54-foot sternwheel steamboat named the “Explorer”.

Public Domain Image*

This boat was to be constructed at the mouth of the Colorado River, at the point where it empties into the Gulf of California, in Mexico. From here, Ives would navigate upstream past present-day Yuma, Arizona and northward toward present-day Lake Mead. The voyage would then lead to the east, and into the Mohave Canyon and the deep dark chasm of the Grand Canyon.

Ives and his crew spent the winter of 1857/1858 making their way upriver. The “Explorer” proved to be a stable craft, and despite a precariously slow and rocky ascent of the rapids in the western depths of the canyon, proved seaworthy in every way. In areas of shallow water, the crew would often disembark and use ropes to assist the ship’s progress by pulling her along from the upriver shores.

Numerous native tribes were encountered along the route, largely with favorable greetings, commerce and merriment. Curiosity on the part of the natives was undoubtedly peaked. Nothing so bizarre as a bunch of white dudes on a steamship had ever been witnessed in this area, and likely not even imagined.

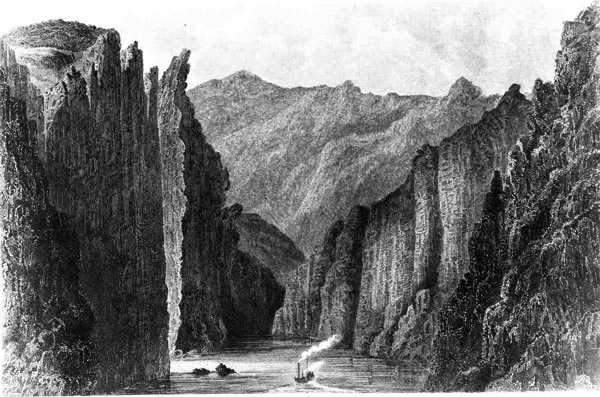

As the river became more difficult to ascend due to rocks, violent waters and narrowing canyon walls, Ives was forced to abandon further upstream travel with the Explorer just below Black Canyon. A crash into a jagged rock had inflicted damage upon the ship, but she was repaired. Nevertheless, Ives decided at that point that it would be safest to investigate the waters further upstream in a skiff.

Public Domain Image*

He ventured some thirty miles into the canyon, and then continued on foot into Diamond Creek, today a section of the Hualapai Indian Reservation.

Following the journey, Ives submitted a report to Congress in which he concluded that despite the astounding magnitude of the canyon, there could be no reason to hold significant interest in this area of the West.

Here is a link to Ives’ report to Congress.

“The region is, of course, altogether valueless. It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado river, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

Joseph Christmas Ives – 1858

John Wesley Powell

Following the Civil War, the nation was flush with battle-tested badasses. The opportunity to explore the unknown reaches of the American West was appealing to many veterans who were not content to settle down for a family life on small eastern farms.

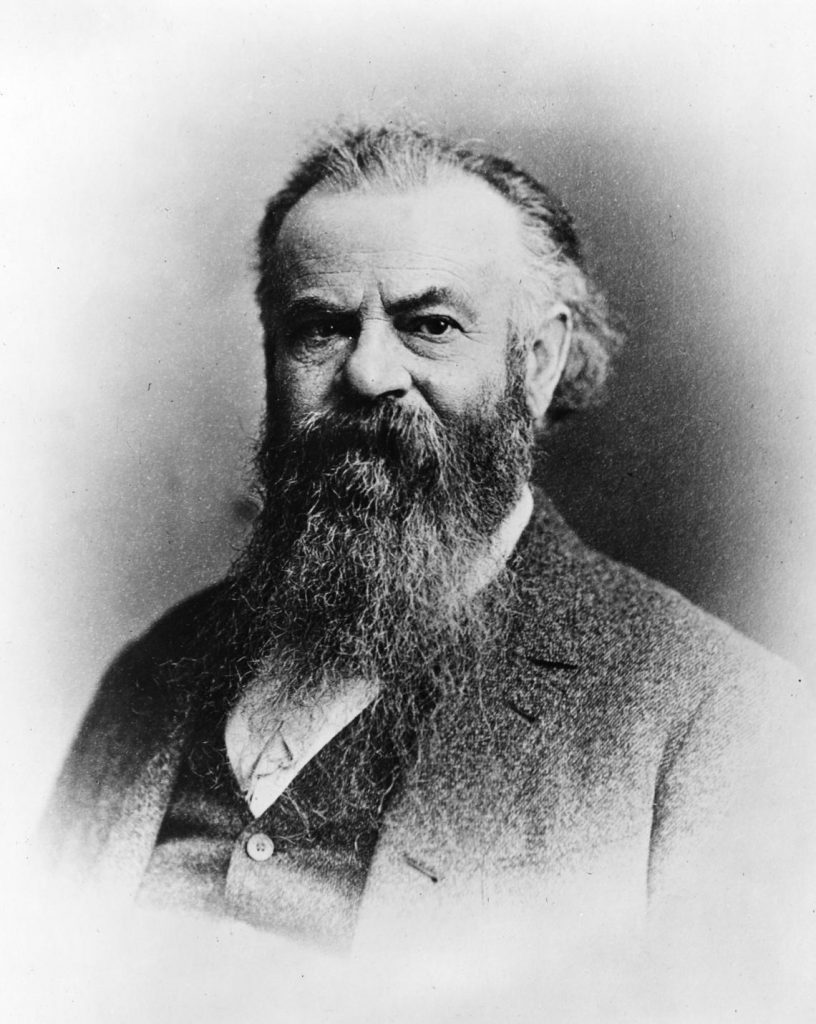

Despite the prediction of Ives in 1857 that no white man would ever again seek to enter the “profitless locality” of the Grand Canyon, a war-veteran and geologist named John Wesley Powell nevertheless set his sights on “the great unknown”.

Powell was born in 1834 in Mount Morris, New York, to a poor English immigrant family who moved westward, finally settling in Illinois. Adventure seemed natural to the young man. Early personal expeditions led him to walk across the state of Wisconsin and to row the length of both the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The young geologist was elected to the Illinois Natural History Society at the age of 25.

After a number of years studying natural sciences at Illinois and Oberlin College, the Civil War kicked off. Powell promptly enlisted as a private in the 20th Illinois Infantry to fight for the Union. Soon commissioned a lieutenant, Powell went on to eventually lose his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh in April of 1862. Despite his injuries, he went on to serve in a number of battles. An eager young study, he continued to advance in the ranks. He attained the rank of Major and ending the war as a Brevet Lieutenant Colonel.

Public Domain Image*

Following the war, Powell accepted a position as a professor of geology at Illinois Wesleyan University. His post allowed him considerable opportunity for field study, which took him into the American West. He organized a number of expeditions that led into the Rocky Mountains of Colorado where he and a group of men became the first recorded white men to summit Longs Peak in 1868.

A lifetime of adventure had prepared Powell to be as qualified as anyone to lead a mission into nearly any place imaginable. In 1869, the one-armed Civil War veteran turned geology professor would get his chance to forever write his name in the history books.

Powell’s First Expediton – 1869

While exploring in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, Powell heard stories of an unknown labyrinth of canyons in the desert southwest. These lands were divided by the mighty Colorado River, and Major Powell was a sucker for river adventures.

The geology professor began research into the area, studying Ives’ Congressional reports and the crude maps of the day. He hatched a plan to embark on a risky journey to float down the river, and through the “great unknown”.

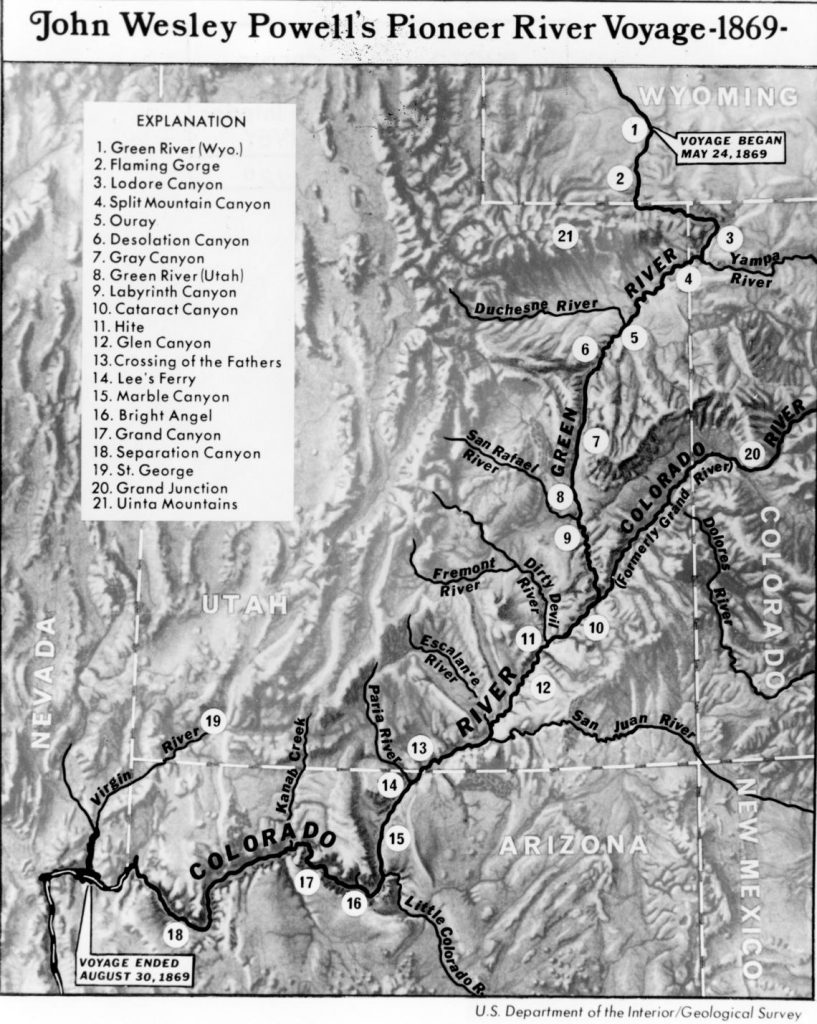

He acquired financial backing from a number of benefactors, including the Illinois Historical Society, and the Chicago Academy of Sciences. The US Congress authorized the donation of rations from the US Army. The Union Pacific Railroad shipped his boats from Chicago to Green River, Wyoming, from where the expedition would begin.

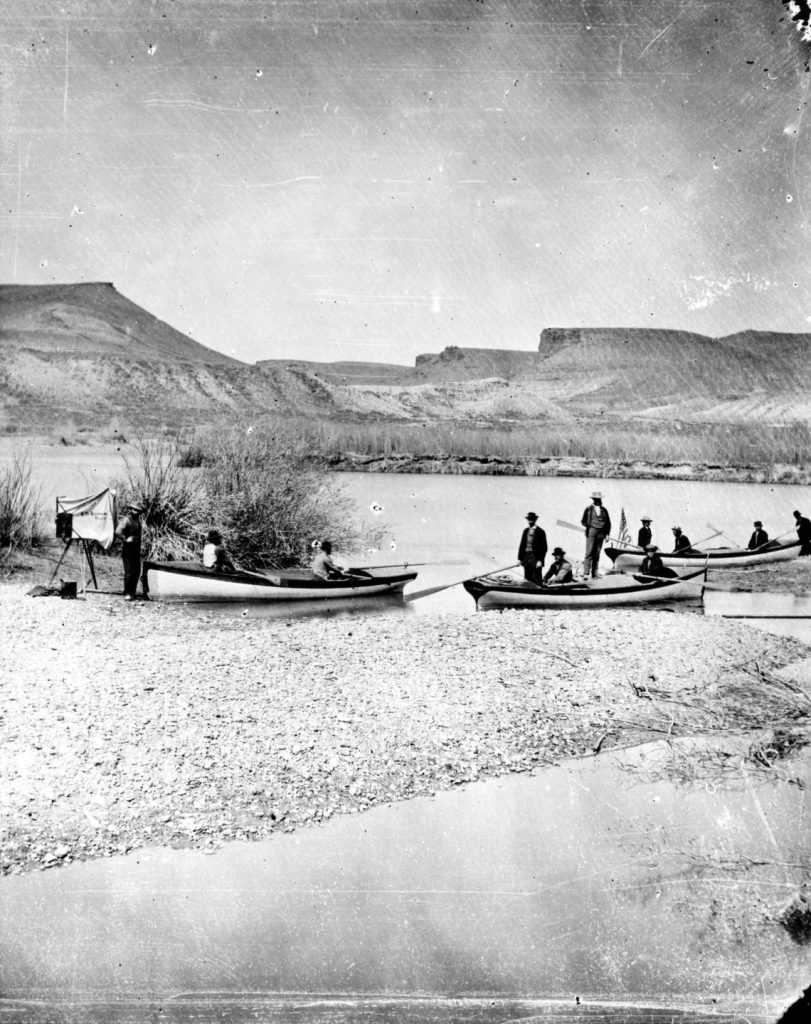

USGS image

Major Powell recruited a team of rugged men, who were well-versed in the hard life. A group of Civil War veterans, fur trappers and mountain men joined the professor for what would be a harrowing journey through the last unmapped region of the the lower 48.

A crew of ten shoved off on May 24, 1869. Among the men heading into the great unknown was Powell’s younger brother, a fellow Civil War Army Lieutenant who was spent ten months as a prisoner of war. Major Powell referred to his brother as “Old Shady”.

The group consisted of four guides, an 18-year-old mule driver and Indain scout and strangely, an Englishman who expressed great interest in the journey and seemed just crazy enough to head into the wild.

Into the Grand Canyon

Spirits were high as the men departed. Aboard the three 24-foot-long wooden boats were rations that should last the group for ten months, and a supply of rifles and ammunition would provide wild game to augment their diet. Powell’s boat, the fourth craft in the fleet, was a lighter and faster 16-foot pine boat that held less cargo, but was more nimble in rougher waters.

It did not take long to realize the rugged nature of the rapids in store further downriver. Just 80 miles into the journey, at a place Powell would dub “Disaster Falls”, one of the boats crashed into a rocky cut, overturned and was destroyed. They crew escaped harm, but the loss of the boat meant the loss of one-third of the crew’s rations.

Soon after, the English chap would exit the group and climb out of the canyon to return to society. As the strength of the rapids increased, Powell ordered physically-taxing portages around many of the more intimidating rapids. There were hundreds of such occurrences, but Powell knew he could not afford another loss of a boat and its priceless supplies. This was no walk in the park…

Despite the fact that the boats were designed to provide dry storage for the food and ammo, even the smaller rapids soaked the entire boat, and soon left the rations spoiled by mildew. This combined with an ever-increasing number of narrowing rapids and darkening vertical walls transformed the expedition into a fight for survival.

Separation Canyon

Three months and hundreds of life-threatening rapids had passed by August 27th. On that day, the expedition arrived at what one member of the crew described in writing as “the worst rapids yet”.

The group made camp above the rapids and weighed their options. Several of the men pleaded with Powell to end the expedition and climb ou to the rim. They wanted to walk to Mormon settlements some 70 miles to the north.

Public Domain Image*

Powell was steadfast in his determination to see through the epic journey he had began. The one-armed Civil War hero felt that the end must be near, but he could only surmise what was to come, as no one really knew… Talk of separation was surfacing as the evening fell upon the camp and it became clear that Powell would not abort his mission.

“The billows are huge and I fear our boats could not ride them…There is discontent in the camp tonight and I fear some of the party will take to the mountains but hope not.”

Major John Wesley Powell – August 27th, 1869

The Major told his men that he would continue downriver if only one other man would go with him. In the end, five of the remaining nine crew members remained with their leader. The opposing three would hike out to the north at a point known today as Separation Canyon.

Powell thought the deserters were taking a dangerous gamble with an early exit into unknown lands. Likewise, the deserters thought the Major insane for continuing into the thundering rapids and raging waves that loomed within the narrow walls of the deep, dark canyon below.

Powell’s remaining crew took two boats, leaving the boat with the most damage behind. The next two days would prove challenging to the remaining crew. A portage went array shortly downstream as a rope broke while lowering a boat. The wooden craft plummeted down into the raging waters, knocking a man named George Bradley into the waves below.

Bradley escaped injury and reemerged in one piece, but the boat was not to be seen again. This loss left one boat for a crew of five men…. And an unknown stretch of water beyond.

Luck was with the crew however. The following day found the remaining crew floating peacefully downstream from Grand Wash. They entered a landscape in which the dark canyon walls began to open. At this point, Powell and his crew knew that they had just completed what Ives had assumed implausible a mere 12 years prior.

Of the original ten, only 6 would exit the canyon on the river. The three deserters, led by Oramel Howland, left the voyage two days before the end of the treacherous section. Little did they know, they had covered 239 of the canyon’s 277 miles. The three deserters would never be seen again.

Upon emergence from the canyon into the civilized world, the feat of the Major and his men became widely publicized. Papers from coast to coast printed accounts of the epic 13 week journey that covered nearly 900 miles and the perils endured by the rugged river runners. The fate of the three deserters was a common subject of journalistic speculation. The journey, and its one-armed Civil War veteran leader, were quickly becoming national legends.

Simultaneously gaining legendary status was the large, previously blank space on the map, which Major Powell had began to refer to as… The Grand Canyon…

Powell’s Second Voyage – 1871-1872

Powell’s first journey down the river did little to improve the advancement of scientific knowledge. The interior of the canyon had commanded more concern for mere survival than for science. Exiting what Major Powell referred to as “our granite prison” alive had become the sole desire of the crew.

Despite the adventurous success of the 1869 descent, the scientific findings of the voyage paled against the wishes that Powell held for the trip. Most of the writings and recordings that had been made in the canyon had been lost or destroyed. The latter part of the trip was without scientific instruments, as the sextants, chronometers, compasses and barometers had all been broken during the carnage of the first trip.

With the luxury of a household name in the the early 1870s, Powell was poised to make a strong case for the funding of a second trip. Financial support for a second voyage came from the Smithsonian Institution and a small congressional appropriation. This journey was to include a surveyor, and several scientists, along with a photographer and an artist to record never-before-seen images of the inner canyon.

Public Domain Image*

Planning for the second trip down the Grand was easier than for the first. Powell now had firsthand knowledge of the canyon and knew the game. For this journey, he would store cashes of food at points along the route and would use redesigned boats that would better withstand the raging waters of the Grand Canyon’s fierce rapids.

The second voyage went off without a hitch. The journey produced the maps and scientific documentation that Powell had envisioned for the first descent of the canyon. In addition to the topographic and geologic information gleaned from the mission, the crew also collected a great deal of ethnographic information regarding the Native peoples that were encountered along the banks of the river.

Powell formed a great interest in the affairs of the native tribes and was insistent on spending time with those whose company was offered. He learned of their language and custom whenever time allowed and attempted to cultivate positive relations with the tribes of the area.

Following the trip, Major Powell focused on compiling the scientific data collected during his voyages. His concentration on topographic pursuits brought him into the realm of the newly created US Geological Survey, of which he became the second director in 1881. His interest in Native American culture led him to a position as the founding director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology in 1879. He would hold this position until his death in 1902.

Mining in the Grand Canyon

Following Powell’s successful journeys into what he began to refer to as the Grand Canyon, prospecting entrepreneurs began to evaluate the financial treasures held within. Miners filed in over the next couple of decades. By the 1890s, lucrative copper mines began to dot the landscape.

It is the presence of the miners that brought initial services to this remote location. These men and their families are solely responsible for the infrastructure that developed at the South Rim. John Hance, a prospective asbestos miner and his partners built the first road into the area in 1885. Many of the trails which access the inner canyon were originally mining trails or exploratory routes. Many of the miners who gave up on their mining schemes went on to use their knowledge to guide tourists into the most-revered sights in the area.

Dan Hogan’s Orphan Mine

A prospector from Flagstaff named Dan Hogan found his way to the Grand Canyon in 1890. He and a group of friends made the first known Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim journey through the canyon in 1891.

Hogan wasn’t there simply to hike and enjoy the scenery. He had an eye for profit and was looking to find an entry into the lucrative mining game. The young would-be miner began to explore the canyon, seeking specific colors that would indicate the presence of copper. Hogan constructed trails that led through areas that most would not tread.

The Battleship Trail led outward from the Bright Angel Trail. It lead 3.5 miles to the west to what would eventually become a profitable mine site. A second trail to this mine, which Hogan called “The Slide”, provided a real white-knuckle affair for many who accompanied the eager young trailblazer. These guests came to refer to this route as the “Hummingbird Trail”. You had to be a hummingbird just to hang on!

Within three years of his arrival, Hogan had filed a copper claim on the piece of land to which his trails led. This site became known as the Orphan Mine, and sat 1,000 feet below Maricopa Point.

Hogan held the mine for more than 50 years. In 1936, he opened the Grand Canyon Trading Post, which served the growing number of tourists that were coming to the new national park. In 1946, Hogan sold his holdings to Madeleine Jacobs, who initially simply continued the tourists operations. Soon however, she would realize she was sitting on a fortune. Not in copper or tourism dollars, but in uranium.

It turned out that the Orphan Mine was far richer in uranium than it ever was in copper. Jacobs sold the mine to the Golden Crown Mining Company, who would operate it from 1953 to 1969. During this period of time, the mine produced more than 4 million pounds of uranium oxide, which brought in over $40 million.

Pete Berry’s Last Chance Mine

Hogan wasn’t the only miner to arrive in the early 1890s. A few other gentlemen arrived about the same time and set up shop at what became known as Grandview Point.

Pete Berry, along with brothers Niles and Ralph Cameron, found a lucrative spot on Horseshoe Mesa, where they established the Last Chance Mine. This mine produced the purest grade of copper ever found in the Grand Canyon. To access their fortune, the men worked quickly to construct what is today the Grandview Trail.

Sensing a profitable future in the tourism industry at the Grand Canyon, Berry and his wife Martha used the profits from their mine to construct the Grandview Hotel in 1897. They promoted the establishment as the “only first-class hotel at the Grand Canyon“. While the Berry’s efforts focused mainly on the Grandview area, the Cameron brothers began to make improvements to the nearby Bright Angel area.

Ralph Cameron

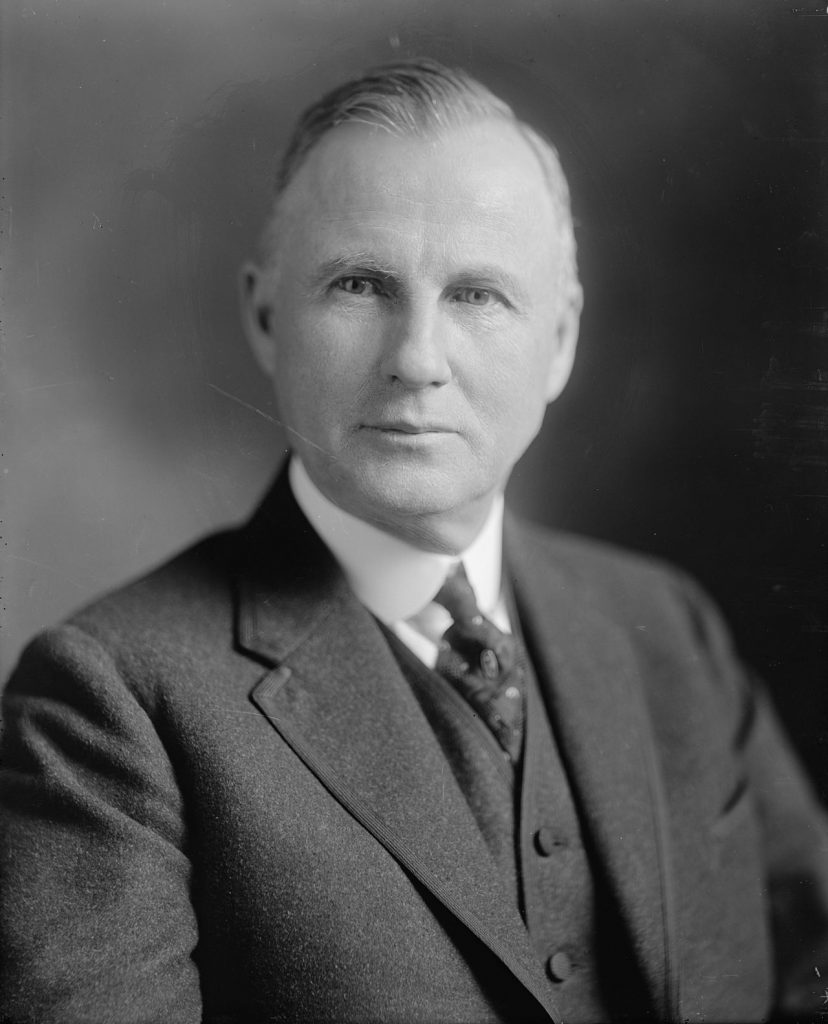

Of all the people who wielded influence upon the Grand Canyon during the early “wild west years, none provided more controversy than Ralph Cameron.

Born in Southport, Maine in 1863, Cameron first learned of the Grand Canyon from reading John Wesley Powell’s account of his explorations of the Colorado River. A young Cameron was intrigued and moved to Flagstaff, Arizona in 1883 at the age of 20.

An eager young entrepreneur, Cameron became involved in politics early on. Within a few short years, he began working to create a new Coconino County, which was formerly the northern part of the massive northern Yavapai County. His effort proved a success and in 1891 Governor John N. Irwin appointed him the first country sheriff of Coconino County. He won re-election twice and quickly became well known throughout the state’s political circles, serving as a McKinley delegate during the 1896 Republican National Convention.

Public Domain Image*

Upon arrival at the Grand Canyon, Ralph Cameron quickly assessed the economic opportunities in the area’s rising popularity. Although ostensibly in the area to seek mining claims, many of the opportunistic Cameron’s claims were situated in areas with some of the finest views, and where profitable mining ventures seemed unlikely.

The Bright Angel Toll Road

Along with his brother Niles and their partner Pete Barry, Ralph Cameron filed mining claims in Bright Angel Canyon. They worked to improve a rudimentary Havasupai path which would become the Bright Angel Trail. As time passed, it became clear that there was far more money to be made in the tourist trade, and mining became a side-hustle. The Bright Angel Trail was named “The Bright Angel Toll Road” and Cameron’s efforts became focused on visitor services. Initially, despite its name, no toll was collected for use of the trail. This would soon change.

The enterprising miner soon built Cameron’s Hotel and Camps at the top of the trail, and put his brother Niles in charge of a tent camp at Indian Garden. Knowledge of a coming railroad led Cameron to negotiate a deal which would place the end of the railroad just below his hotel, ensuring a steady stream of wealthy patrons.

However, the railroad company had also made a deal with Martin Buggeln, owner of the Bright Angel Hotel. When the railroad arrived in 1901, the tracks were laid right past the Cameron Hotel and continued to the Bright Angel Hotel. Further Cameron was forbade from soliciting arriving travelers at the station.

This infuriated Cameron, who immediately began charging a toll of $1 for passage onto the Bright Angel Trail. Lawsuits ensued, but given Cameron’s local political ties, nothing came of them. Sensing that he needed more political sway for a slew of upcoming legal battles, the embattled businessman ran, and was elected to the Coconino County Board of Supervisors in 1904. The next year, Cameron became the chairman of the board.

In 1906, when Cameron’s franchise registration for the toll road at the Bright Angel Tail expired, the Santa Fe Railroad applied for the rights to operate the road. The railroad sweetened the pot by offering a substantial percentage of the toll’s earnings to the county. The county, with Cameron as chairman of the board, rejected the railroad’s offering and awarded a new five-year contract to Cameron in 1907. The railroad sued, and a lengthy battle began that would lead all the way to Washington DC.

A Prominent Visitor

The arrival of the train at the South Rim spurred economic development overnight. Hotels and eateries began popping up in increasing numbers . Photo studios and gift shops greeted the masses who disembarked at the Grand Canyon Station. The public was intrigued and everyone wanted to see the incredible sight of the canyon.

One of the most prominent people to ever visit the Grand Canyon arrived by train at 9:30 am on May 6, 1903. This man was an avid outdoorsman; a curious type with an unending appetite for adventure. His favorite times were spent pursuing, “the strenuous life” as he put it. He was a big game hunter and rancher by hobby, but his real job was something completely different. This man had real power.

A Sight Every American Should See

President Theodore Roosevelt was touring the American West, just two years after an assassin’s bullet had ended the Presidency of William McKinley in Buffalo, New York, propelling then Vice-President Roosevelt into the highest office in the land.

Roosevelt’s thirst for knowledge and exploration led him to embark on his western journey. The trip would cover 14,000 miles in just over two months. The President wanted to see the Grand Canyon, and many of the other western sites. He was especially eager to get to Yosemite National Park, where he would enjoy an epic adventure with the famous naturalist John Muir.

Public Domain Image*

Upon arrival, Roosevelt and a small group quickly mounted horses and rode out to survey the area. By the time of his return, a crowd of some 800 people had gathered. The elated statesman gave a speech from the balcony of the Grand Canyon Hotel. His words are now canonized in American history and national park lore.

“I hope you will not have a building of any kind, not a summer cottage, a hotel or anything else to mar the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the loneliness and beauty of the canyon.

“Leave it as it is. Man cannot improve upon it; not a bit. The ages have been at work on it and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights which every American, if he can travel at all, should see.”

President Theodore Roosevelt – May 6, 1903

The President’s visit was short; he was gone by 6 pm. Off into the sunset…

His impression of the Grand Canyon, and the lingering effects of the enjoyment he experienced there however, was not short. Once back in Washington DC, the President began to consider the means by which he could lend assistance to the preservation of the landscape of this region of northern Arizona. He had little in the way of political support for another national park. But there may be a way…

Grand Canyon National Monument

Roosevelt may have lacked the ability to pass legislation to create a national park at the Grand Canyon, but that didn’t mean he had no cards to play. The President was alarmed at the amount of development he saw at the South Rim. He was further concerned about the potentially destructive mining practices that were taking place below the rim. It took a few years, but the President eventually made his move.

On January 11, 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt created the Grand Canyon National Monument. The land encompassed by the monument would contain more than 800,000 acres and would prevent further unencumbered development. The designation would also restrict mining practices, although may such activities would continue for decades to come.

Arizona Statehood

Up to this point, Arizona had merely existed as a US Territory. The land of the Grand Canyon had very limited political clout on the national stage as a territory. Many Arizona residents held a desire for statehood, but success on that front was slow to come. The only position that could affect any change on this front was the position of Territorial Delegate. One Arizona resident was motivated to attain statehood for his newfound homeland, and he ran for Territorial Delegate in 1908.

Ralph Cameron won the position. He worked eagerly to achieve statehood for Arizona, and to gain new political allies of ever-increasing prominence. His efforts to promote statehood were effective. In February of 1912, President Taft signed the bill which granted statehood to Arizona.

Public Domain Image*

During the run-up to statehood in 1911, Cameron had thrown his hat into the campaign for Senate, but lost. It would not be his last attempt to gain power in the newly formed state.

Hermit Camp

Meanwhile, the Santa Fe Railroad began to work on options that would allow their visitors to access the lower regions of the canyon without the use of Cameron’s trail. By 1911, work began to construct the Hermit Trail, which would lead all the way to the Colorado River. This trail was by far the nicest in the park. Intricate stone walkways essentially “paved” vast sections of the route. This trail offered a pleasant hiking experience for tourists, especially compared to many of the unimproved mining trails in use at the time.

At the river, the company built a luxury camp. This retreat offered services that were the pinnacle of opulence for backcountry camping in the early 20th century. Tent cabins, toilets, showers, phones and private chefs were among the amenities that made the Hermit Camp the most popular destination in the Grand Canyon.

Here too however, arose problems between the railroad and Ralph Cameron. Numerous sections of the Hermit Trail were laid across mining claims that the newly elected politician had previously filed. He erected notices of trespass at his claims and filed lawsuits that delayed construction of the trail. In the end, the Santa Fe Railroad paid Cameron $40,000 to allow the project to proceed.

Changing of the Guard

During the early 20th century, the numbers of visitors to the Grand Canyon continued to grow. In response, larger business interests began to invest in the growing tourist economy. Increasingly, small proprietors such as Pete Barry and Ralph Cameron saw their operations sidelined by well-funded corporate entities such as the Santa Fe Railroad, in coordination with the Fred Harvey Company.

In 1905, the Santa Fe Railway built the El Tovar Hotel, just a stone’s throw from their railway depot. This extravagant complex was managed by the Fred Harvey Company. This company was gaining a reputation for hospitality along the railways of the Santa Fe. The famous “Harvey Girls” provided prompt, professional and courteous service at fine eateries and shops in and around the hotel.

Pete Barry, whose Grandview Hotel had once been promoted as the “only first-class hotel at the Grand Canyon”, saw his profits evaporate with the arrival of the railroad. His location at Grandview Point stood miles from the depot. Barry constructed a road from the railway depot to his hotel. He offered free stagecoach transportation on a road he had constructed to Grandview Point. He and his wife had sold their mining claims in 1902, but had held the hotel.

The Barrys fought to maintain a relevant stake in the growing business at the Grand Canyon. However, they were far outmatched financially. Limitless funds from the railroad were poured into luxury accommodations that simply outclassed the rustic appeals of the smaller “mom & pop” hotels. The railroad had offered to buy the Grandview numerous times, but the Barrys had always held out.

Finally, by 1913, the Barrys could not continue, as their losses began to take toll. An indignant Pete Barry would not sell out to the corporate machine however. Instead, the Grandview was sold to newspaper magnate, William Randolph Hurst. Barry despised the corporate and federal development that was taking hold at the South Rim. He thought, accurately, that Hurst would prove a great annoyance to the railroad, and to the federal government.

Meanwhile, waining profits forced Ralph Cameron to close his hotel and the nearby camps in 1909. He maintained numerous other businesses, such as the Indian Garden Camp. He also continued his hold on the Bright Angel Toll Road and its $1 per person fee.

Cameron continued in his political ascendency, attaining a seat as a US Senator for the state of Arizona in 1921. He would not relinquish his hold on the Bright Angel Trail until 1927. Arizona voters declined to elect the controversial Republican a second time. His political clout began to fade, as did his hold on the Grand Canyon enterprises he had held so tightly for so long.

Following his death in 1953, Cameron was buried in the Grand Canyon Village Cemetery.

Mary Jane Colter

As development progressed at the South Rim, a number of new structures went up every year. The rustic appeal of the American West was an attraction for many visitors. Yet modern 20th century architecture held an appeal for many designers.

For the tasteful student of modern design however, the Southwest had a style all of its own. Timeless forms of natural and Native American design could be implemented to preserve the past, while providing an esthetic appeal that would last far into the future.

The Fred Harvey Company had a number of hotels and restaurants lining popular railway routes throughout the western US. A recently discovered architect had attracted attention with her interior design at the new Alvarado Hotel in Albuquerque in 1902.

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter was born in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania in 1869. After attending the California School of Design in San Francisco, she took a teaching position in Minnesota. Unsatisfied with the classroom after a few short years, the young architect found a position with the Fred Harvey Company. Her success in Albuquerque grew her reputation quickly. Soon her talents were focused on the developing village at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon.

Colter’s unique gift seemed to be her ability to blend natural materials and forms into her work. Her first Grand Canyon project, was the Hopi House. This structure was modeled after the 1,000 year old pueblo dwellings in Old Oraibi, an ancient Hopi village in northeastern Arizona.

Colter also worked as interior decorator in the El Tovar Hotel. She would soon take the position as the chief architect and decorator for the Fred Harvey Company. Her time at the Grand Canyon would produce 6 structures. These included the Desert View Watchtower, the Phantom Ranch canteen, the Bright Angel Lodge, Lookout Studio, and the Hermits Rest structure. In addition to these, Colter designed more than 20 hotels, lodges and structures for the Fred Harvey Company over a span of 46 years spent with the company.

Colter retired from Fred Harvey in 1948 at the age of 79. She passed away a few years later, at the age of 88.

Grand Canyon – A National Park

With the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, attitude toward the vast nation’s vast landscapes was shifting from an extraction model to one of preservation. Many who supported the idea of a national park at the Grand Canyon saw it as only a matter of time before this vision would become reality. Public sentiment seemed to support the idea, despite the pushback to federal encroachment from locals such as Ralph Cameron.

In April of 1917, Arizona Senator Henry Ashurst, whose father had explored the inner canyon as a mining prospector just decades before, introduced Senate Bill 390. The bill provided for the creation of a Grand Canyon National Park.

The beginning of World War I and numerous legal battles, such as those surrounding the Bright Angel Toll Road, delayed the passage of the bill for a length of time. However, once the matters of law were debated thoroughly by teams of attorneys, the bill sailed through the house and the senate.

On the 26th of February, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill into law. Arizona had its first national park and the nation had its seventeenth:

Grand Canyon National Park…

Guide to Grand Canyon

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.