I don’t specifically recall my first interaction with Rec.gov, but I’m sure that it sucked.

Odds are, “my first” was probably a lottery application to visit The Wave, nearly a decade ago. This iconic sandstone feature, located in northern Arizona’s 112,500-acre Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, somehow gained notoriety among outdoorsy folk well before the emergence of Instagram. I remember applying for this permit, paying my application fee, and getting absolutely nothing in return.

I would post a nice photo of The Wave at this point in the article, but to this very day… I’ve still never been there.

My Wave story is far from unique. According to the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the Wave, some 200,000 people applied for 7,300 possible permits in 2018 alone. That means 192,700 applicants were unsuccessful, and those folks don’t get a refund on their $9 application fee, although I think the fee may have been $6 back then.

Oh well, at least that money goes to the park, right? Those lottery fees likely finance new picnic tables, restroom facilities, or they address massive maintenance backlogs?

Nope, not a chance… All that lottery fee money stays with Rec.gov my friend, every red cent of it…

But wait, isn’t Rec.gov a government website? Isn’t that site administered by the National Park Service, or the the BLM? Department of Interior, or the Forest Service? Department of Agriculture? Someone? Anyone? Bueller…? Bueller…? Bueller…?

Crickets…

Rec.gov is Everywhere… & Nowhere

Any modern-day public land visitor who ventures into the backcountry of his or her local park has likely found the need to utilize the Rec.gov system to secure their chosen adventure, especially if it requires an overnight stay or has limited visitation regulations, which for some reason, are increasingly common these days.

In fact, many of our nation’s most popular national parks, such as Rocky Mountain, Glacier, Yosemite, Arches and Acadia, now require reservations to enter their most popular areas, which can only be attained through Rec.gov.

A quick visit to the Recreation.gov website’s “About” section reveals that their system is widely used, and the numbers are staggering. The page encourages guests to “Bring Home a Story”, lists an array of alluring outdoor activities, and includes a number of impressive statistics and affiliated government agencies. The content and design of the page effectively convey a feeling of competence and security, all while advertising pure adventure.

According to their figures, Rec.gov controls access to more than 113,000 recreation sites in some 4,200 locations. These range from Florida’s Everglades to Maine’s Acadia National Park and from California’s Joshua Tree, to Alaska’s Denali National Park. They report in excess of 21 million users, who access lands managed by everyone from the National Park Service and the National Forest Service, to the Bureau of Engraving & Printing, the National Archives and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Wow… These guys definitely have their hand in the outdoor adventure game, and apparently, a few other games as well. I mean, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing? Really?

Anyway, it seems Rec.gov is right in the middle of the thicket there in the nation’s capitol. But for some reason, their website doesn’t really give much information about their structure, it just lists 13 separate federal government agencies as “Our Partners”.

So Who IS Rec.gov?

If one is easily pacified, the questions may simply end there. These guys appear to be partners of the federal government, perhaps some kind of quasi-government organization.

But somehow, the “partner” term just doesn’t seem to align with any form of government organization I recall learning about in my social studies classes, or my political science classes, or through life in general. So the question remains: Who is Rec.gov?

Ten minutes on the interwebs provided an answer, as the information is not difficult to find. Turns out, Rec.gov is not a construct of the federal government, or a newly formed alphabet agency tasked with serving the nefarious wishes of runaway Executive branch. Nor is it a government agency created to manage public land visits. Not quite. It is a private entity, owned by a company that remains relatively removed from the public eye, although they certainly raised quite a few eyebrows about a decade ago.

Rec.gov, it turns out, is the recently-adopted, yet likely beloved, stepchild of a massive corporation named Booz Allen Hamilton, which holds a bevy of government contracts, many of which appear to be connected to national defense and data collection.

The Booz Allen “About” Page, does little to really describe what exactly they do, but does promise that they “bring bold thinking and a desire to be the best in our work in consulting, analytics, digital solutions, engineering, and cyber, and with industries ranging from defense to health to energy to international development“.

While many readers may not immediately recognize the corporate name, Booz Allen Hamilton, they will likely recall the company’s most famous employee: Edward Snowden.

Now, Edward Snowden doesn’t have anything at all to do with national parks, but neither does Kevin Bacon…. or does he?

Politically aware news junkies who remember the hyper-active nature of the national security state in the decade following the September 11 attacks of 2001, may recall that Snowden worked for Booz Allen as a IT guy, handling a number of highly classified documents.

Of course, Snowden elected to, well… “declassify” that information, and that’s probably the only reason the majority of common folk ever heard of the company I now refer to as “The Booz”.

Spies Like Us… “The Booz”

At the time of Snowden’s leak in June of 2013, the surveillance-state-philosophy concerning personal data was to collect, collect, collect, and when asked about such activities in public, or in front of the Senate, deny, deny, deny.

Snowden’s leaked documents revealed that federal alphabet agencies were indeed, collecting a trove of information in the form of phone records and emails of American citizens. This fact had been previously denied in Senate hearings by National Security Administration Director James Clapper, who it turns out was a former executive at… non other than Booz Allen Hamilton.

Here’s General Clapper’s classic response to the question of whether the NSA collects any type of data on millions of American citizens. You may recall the main point of interest at 6:40. Keep in mind, this hearing was prior to Snowden’s release of classified documents that proved otherwise.

You really can’t make this shit up… & it doesn’t stop there. The list of Booz execs who reside in the confines of Washington’s “revolving door” are many in number.

Mike McConnell was a former Booz exec when he took a position as the Director of National Intelligence for George W. Bush, and returned to the Booz after his term as DNI. A top cybersecurity aide to McConnell while he was DNI, Melissa Hathaway, is also a former Booz executive, as are former Central Intelligence Agency director James Woolsey and deputy director Joan Dempsey.

The list of heavyweights goes on & on… The Wikipedia list of this company’s associates is a who’s who of the post 9/11 surveillance state, with representatives from the NSA, CIA and Department of Homeland Security constituting the majority of the list.

Today, the Booz employs nearly 30,000 people in 80 offices worldwide, more than half of whom have “classified” security clearances, while a smaller number is reported to have “top secret” clearance, according to Bloomberg News’ 2013 article “Booz Allen, the World’s Most Profitable Spy Organization”.

Why is The Booz involved in National Parks?

It’s only natural to wonder how a top-level cyber-spy company finds their way into a public land permit and reservation scheme. But a quick point will easily explain this:

Quite simply, it’s easy money for a company with a level of technological expertise such as that of The Booz, and perhaps more importantly, they have the political connections necessary to land such a contract.

Payments for their defense related contracts likely range well into the billions of dollars, and thus the public land permit scheme may seem small by comparison, but constructing an online reservation system is just not a lot of work for such a cyber-savvy company. These guys aren’t exactly amateurs.

Combine the relative ease of task with the fact that this company has connections throughout the top levels of the federal government, and they become the perfect fit to design an online management system for public lands that receive more than 300,000,000 guests annually. As Drake Bennett and Michael Riley wrote in their aforementioned Bloomberg article:

“The firm (The Booz) has long kept a low profile—with the federal government as practically its sole client, there’s no need for publicity. It does little, if any, lobbying. Its ability to win contracts is ensured by the roster of intelligence community heavyweights who work there.”

So it’s easy to see how The Booz gets this contract. They can do the job and they don’t even need to lobby anyone, as they already know everyone in Washington.

They ARE Washington…

The Birth of Rec.gov

The idea for moving outdoor reservations to an online form began innocently enough in an Ontario garage back in the early 2000s. Originally, a Canadian duo started a company called ParkNet, which according to NPS envoy to Rec.gov, Rick DeLappe, soon thereafter became Reserve America. Eventually, the small company was sold, and ran through a series of owners, including TicketMaster, the Interactive Corp and the Active Network.

These were tough times for the online reservation game, and many outdoor folk who had interactions with the new platforms came away frustrated, or even downright angry. The systems were glitchy, reservations were lost, web browsers crashed and it seemed everyone was complaining about the inefficiencies of the reservation booking industry.

By 2015, federal government land-management agencies were looking for a solution. The parks and public lands were steadily growing in visitation, but the process for reserving and booking permits via the internet was stuck in past decades of internet protocol.

The search for a new “partner” in the booking game ended with the decision to accept a bid from The Booz, who was awarded a ten year, $182 million contract, which began in 2017. In addition to that money, Rec.gov collects 100% of the reservation fees, and the lottery fees associated with the specific reservation selected.

Further, as Lindsay DeFrates reported in her 2019 article “No, Rec.gov Doesn’t Fund Public Lands, Rec.gov gets to set their own rate for reservation and lottery fees. The local land management agency is only owed the permit fee, and as she reports, sometimes, they don’t even receive those.

In her examination of the ticketing system for Sequoia National Park’s Mount Whitney, the highest point in the Lower 48, she found that Rec.gov is making somewhere in the range of $100,000 per lottery for a ticket to the top. And this, as she notes, is just one location out of more than 113,000.

So it’s kinda big money, and seems to be a worthwhile side-hustle, even for the world’s most profitable spy agency.

Business is Booming for Rec.gov

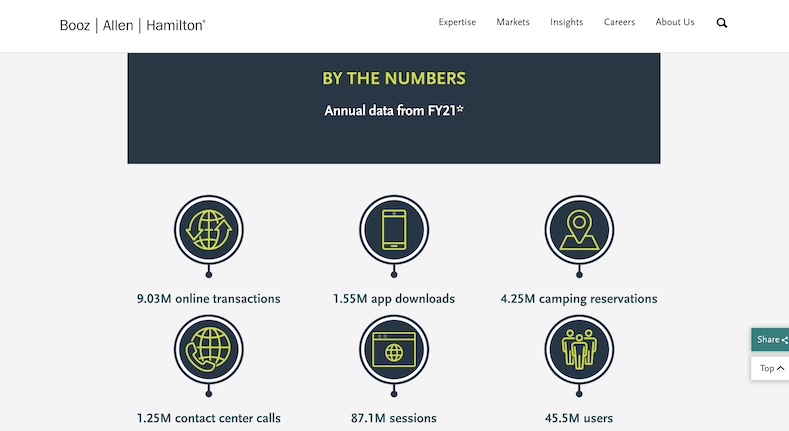

The statistics advertised on The Booz’s website are slightly more telling than those found on Rec.gov’s. According to this page, the company facilitated more than 9 million online transactions, for more than 45 million users. The Rec.gov app received more than 1.5 million downloads and more than 4.25 million campground reservations were attained through their services. Overall, the system handled more than 87 million sessions, and there were more than 1 million contact center calls.

In what many consider a disturbing trend, parks and public land agencies are increasingly moving even more obscure locations into the Rec.gov model.

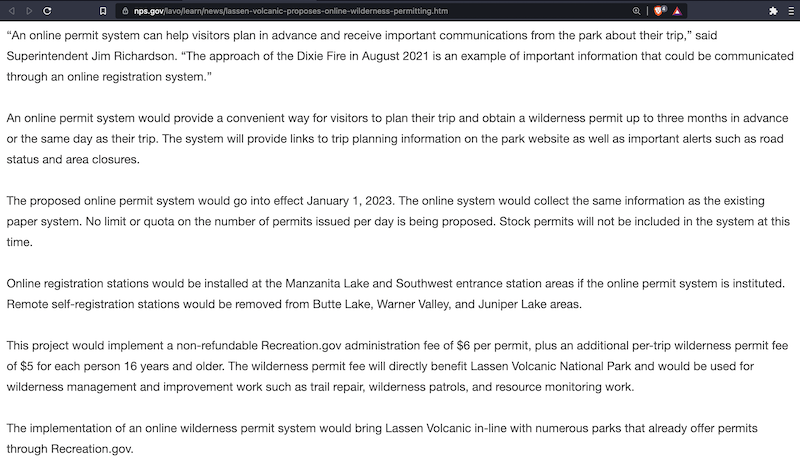

This year, 2022, has witnessed an attempt by Lassen Volcanic National Park to move all of its backcountry reservations to the online platform, going so far as to remove trailside kiosks, which previously allowed spur of the moment hikers to obtain a free backcountry permit at the trailhead. Under this proposal, a fee of $11 per-trip would be implemented, with $6 going to Rec.gov, and $5 to Lassen Volcanic.

Grand Canyon National Park has as of July 2022, locked down the entire north rim along the, scenic, yet desolate reaches of the Arizona Strip. The park’s remote Toroweap Overlook, located at the end of a rugged dirt road some 60 miles in length, now requires online reservations.

In an act of absolute disregard for public access, park officials simply applied this draconian permit system to the entire strip, including within its scope incredibly hard to reach places such as Kanab Point. I’ve been roaming these areas for decades, and have rarely encountered anyone on weekdays at Toroweap, and only recall ever seeing one other party at Kanab Point.

Each year, the structure of Rec.gov adds new and exciting locations, and new activities to the ever-expanding list of possibilities. These days, you can use the online system to obtain permits to hike, bike, paddle, hunt and fish, to list just a few possibilities. Hell, you can now even get a permit to cut down a Christmas Tree.

However, its a sure bet that The Booz won’t be leaving a present under your tree.

Rec.gov gets Money from In-Person Permits Too

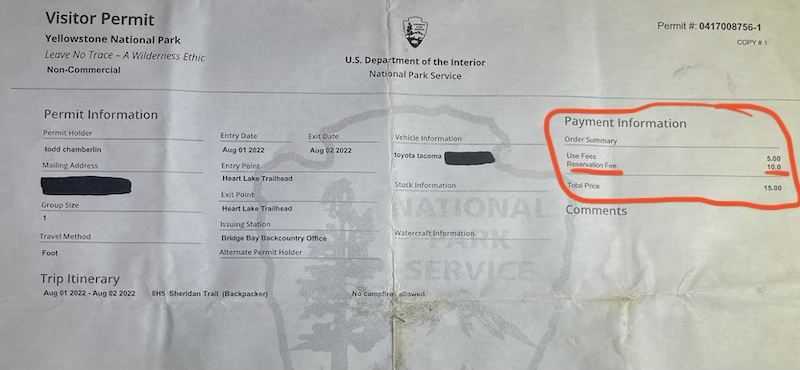

In the case of Yellowstone National Park, all backcountry permits are now routed through Rec.gov, even those that are obtained in person from a ranger on site. I realized this in the summer of 2022, when, hoping to avoid Rec.gov, I entered the Bridge Bay Marina Ranger Station, and requested a permit to camp overnight at Heart Lake, in the park’s southern region.

The ranger showed me the available sites, and I chose one. He then asked for my email, which I didn’t really think about, and charged me $15. When he handed me the permit, I noticed the itemized pricing, which conveyed that the permit fee was $5, and the “reservation fee” was $10. Intrigued, I asked the ranger about the reservation fee, as I did not have a reservation. I was a walk-in, looking for a walk-in permit.

“Oh, that’s because we have to use Rec.gov to make all backcountry reservations” the ranger kindly responded. “That’s just how they want us to do it now. We have to.”

So, in the case of the world’s first national park, any backcountry permit must be issued through Rec.gov, despite the fact that you may be standing in northwestern Wyoming, in front of a ranger who has the permit book in his hand. Such a transaction gives a company located in the leafy confines of McLean, Virginia $10, while giving the backcountry system at Yellowstone $5.

And the public wonders how the national parks are struggling with a $12 billion maintenance backlog…

The Public is Learning About Rec.gov

Over the course of the past few months, as I learned the details of this setup, I’ve talked to hundreds of friends and acquaintances who frequent their national parks and public lands. I am always curious to find if any of them have knowledge of this system. Low and behold, I must report that public knowledge of this Faustian bargain is basically nil.

Out of the hundreds of conversations regarding the Rec.gov arrangement, only ONE of my friends had any substantial knowledge of the private nature of the public land permit and reservation system. Only ONE. And he is a bit of a inquisitive soul, so he sort of investigates things because he just can’t help himself.

However, the story of such manipulation of public land trust is slowly coming to the surface. Just a couple weeks back, well-known finance writer Matt Stoller published a telling piece on his Substack account entitled, “Why is Booz Allen Renting Us Back Our Own National Parks”. Stoller is Director of Research at the American Economic Liberties Project, and a great deal of his work centers on the relationship between the private and public sectors of American finance.

His article focuses largely on the administrative “junk fee” add ons that are the basis for the business model at play in the Rec.gov arrangement with public land agencies. Stoller argues that this is a “scam”, and this author certainly agrees with him. His article goes on to point out the potentially promising news that this arrangement is not permanent, at least not yet.

The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act

The entire Rec.gov permit and reservation system is built upon the basis of the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act of 2004, which effectively authorized the federal government to charge fees for activities and access to public land. This bill contains language which has proven both beneficial and harmful to The Booz.

First, the FLREA provides a roadmap for the implementation of fees on public lands within the control of federal agencies. The act authorizes such fees, in a motion to give permanent authority to public land agencies to charge fees for the use of said lands. This is the gateway used by The Booz to gain a source of income derived from the public’s desire to use its own land.

Secondly however, the same law requires that the public be notified of any proposed fee increases, and that the subject of such a fee increase be addressed through a pubic notice-and-comment period. This led to a small problem for The Booz in 2020, when hiker Thomas Kotab sued the Bureau of Land Management for the $2 processing fee charged to access Nevada’s Red Rock Canyon Conservation Area.

The BLM had failed to provide for a public comment period, and U.S. District Court Judge for the District of Nevada, Jennifer A. Dorsey, found that while Congress had indeed authorized the charging of fees for the purpose of preserving and utilizing Federal lands, it had not authorized administrative fees implemented by third parties. Judge Dorsey sided with Kotab and the BLM and Rec.gov quietly resorted to accepting the comment period.

As Stoller notes however, this is merely a procedural step, and the committees that make fee implementation decisions are not bound by public comment. They merely must accept it. They go on to make their own decisions, often ignoring the actual comments received by engaged citizens.

Calling All Concerned Public Land Users

As concerned public land users, it is incumbent upon us to begin the laborious process of learning about how this system is organized, and how we can obtain some level of meaningful impact upon the decisions that affect our federal lands.

Obviously, it behooves the park-going-public to engage in discussions with such land agencies, and this can be achieved through the public comment process. Up till now, not many publications seem to focus upon the administrative moves of the National Park Service, or the BLM. This needs to change.

While it is a point of Stoller’s piece, that these agencies may simply ignore the public’s submitted comments, it is likewise understandable that often, these comments are relatively few in number.

But what if there were tens of thousands of comments? And what if those people were actually paying attention to the matter at hand? Perhaps this would lead to a different outcome. Too often, decisions affecting public lands are simply made without any real public notice, simply because no one is requesting their input. And why would they?

Also, it is worth mentioning that Stoller’s report also reveals that the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act is up for a Congressional renewal vote in October of 2023. That means that there is a looming opportunity right in front of public land lovers. With a fair amount of public outcry, Congressional members may be inclined to demand changes to the FLREA, and could easily tighten the reigns on runaway fees, such as those charged by The Booz.

A slightly quicker means also exists by which these corporate barons could be reeled in. The White House unveiled the “President’s Initiative on Junk Fees” in late October of 2022. In a move ostensibly made to reduce the negative impact of junk fees on the lives of Americans, the Biden administration reports that it is seeking to lessen the prevalence of such fees in the private sector through actions by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

This could easily be modified to include the Federal land agencies that allow Rec.gov to administer such fees on public lands. Poof… Problem solved…

Well, maybe not solved, but at least it’s an improvement.

Do We Really Need Reservations Anyway?

All of this is very intriguing, and the methods by which federal agencies and corporations move to constrict our lives are ever-evolving in our modern world. Sure, we could clamp down on the confluence of public/private enterprise and perhaps arrive at a workable solution to the permit and reservation fee scheme.

But one has to wonder, do we really need all of these public land reservations? Weren’t our public lands just fine 25 years ago, when no one had ever heard of a reservation to access a national park?

Critics of an open park policy will rant and rave about how busy the parks are, and in some instances, they may have a fair point. But the move to restrict access to the lesser known areas of more remote areas is an obvious money grab, and has no other benefit to anyone.

Our nation’s park-going-public needs to have a conversation, and not just blindly leave such decisions up to the desk jockeys at the National Park Service and the other public land agencies. Do we need these reservations? Do they negatively impact some people more than others? Are there alternatives to the reservation system? Do such systems need to be implemented year-round, or on weekdays? Do we want private enterprise involved in the processing of such programs? What do we want?

Even though there may be those among our ranks who favor a reservation system, because they think it will preserve the natural features of their beloved lands, a conversation must begin. And while some folk may defend the reservation system, it’s hard to imagine any public land user with a knowledge of how this system currently works, defending such a public/private business model.

Thanks for Reading National Park Observer

As you can see, we have a lot to discuss in future publications of the National Park Observer, so I certainly hope you’ll consider subscribing, and commenting on what you feel should be done to address the issues facing our public lands as we move toward a new year.

See ya on down the trail…