The history of Voyageurs National Park stands as an example of a region of great natural resources which became the desire of commercial interests and industry, not only for French-Canadian fur traders, but for mining, fishing, and timber interests as well.

Artist-Henri Julien / Public Domain Image*

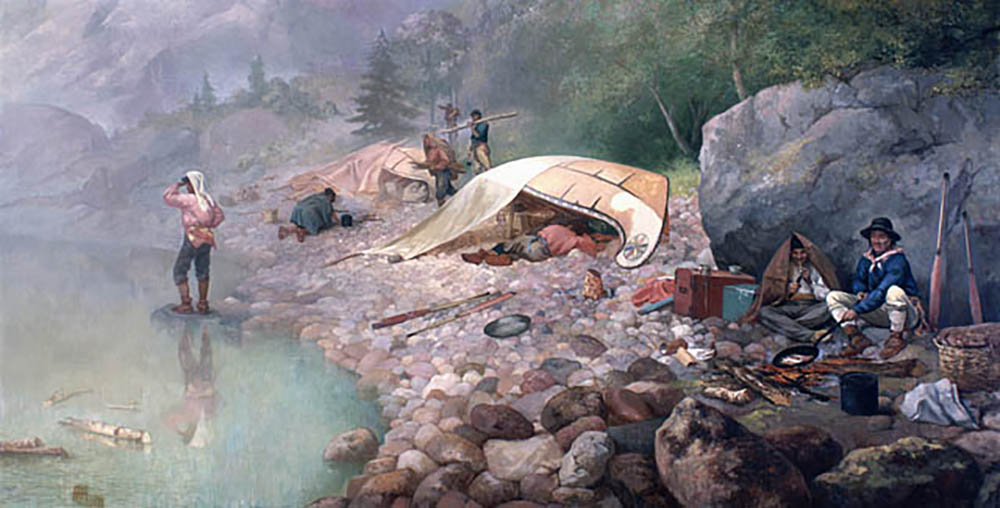

Header Image: Artist-Frances Anne Hopkins / Public Domain Image*

Guide to Voyageurs

Who Were the Voyageurs?

As early as 1688, French-Canadian fur trappers such as Jacques de Noyon had established trading agreements with native tribes such as the Cree, Monsoni, Assiniboin and later, the Ojibway. The area of Voyageurs National Park was renowned for the quantity and quality of its beaver pelts, and was a major transportation route route for trappers taking their goods to the east.

Generally speaking, the Voyageurs were primarily involved in the long-distance transport of furs and trade goods. Often, their transportation routes led to Montreal, Canada, and would cover well in excess of 1,000 miles.

Artist-Frances Anne Hopkins / Public Domain Image*

They operated in organized groups, and commonly held an official license for the task of transportation, as they were often highly valued employees of powerful trading companies such as the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Doureur des Bois

Other hands were involved as well. The coureur des bois operated in a less organized manner. These were often entrepreneurial individuals who acted more as woodsmen, and would usually focus on a wide array of tasks, including the actual trapping of the animal and prepping of the hides for trade.

Artist-Arthur H. Hider / Public Domain Image*

This is not to say the Voyageurs did not take part in the task of trapping. On the contrary, they were able-bodied in all aspects of the trade, and eventually displaced the coureur des bois, as the westward advance of society and the growth of fur trading companies brought more regulatory restrictions, which increased the demand for licensed operations.

Voyageurs as Folkhero

The Voyageurs were hard working men, and developed the reputation of hard playing men as well. Their far-reaching journeys and rugged exploits became the stuff of legends, and they were held as folk heroes by much of French-Canadian society in the 19th century. Their adventurous tales would widen the eyes of young boys, who often held aspirations of joining the Voyageurs when of adequate age.

Artist-Charles Deas-1846 / Public Domain Image*

One old voyageur reported to Minnesota Secretary of State James H. Baker that, if given the opportunity, he’d live the same life over again.

I could carry, paddle, walk and sing with any man I ever saw. I have been twenty-four years a canoe man, and forty-one years in service; no portage was ever too long for me, fifty songs could I sing. I have saved the lives of ten voyageurs, have had twelve wives and six running dogs. I spent all of my money in pleasure. Were I young again, I would spend my life the same way over. There is no life so happy as a voyageur’s life!

The voyageurs were the backbone of the fur trade, and at the peak of the trade industry their numbers grew to include nearly 3,000 men. Numerous routes and millions of acres provided a nearly unlimited potential, and the markets to the east remained hungry for their goods for nearly two centuries.

A Race for Resources

As the urban appetite for furs and beaver pelts faded in mid 1800s, the area of what would soon become northern Minnesota began to attract the eye of industry. The ever-hungry timber industry began efforts to harvest the area’s timber-rich boreal forests.

Commercial fishing operations accelerated in the 1830s with the American Fur Company’s foray into the business. In the latter years of the 19th century, the fishing industry became a multi-million-pound-per-year enterprise that would eventually bring a decline in native fish populations throughout northern Minnesota. By the turn of the 20th century, there were numerous commercial operations on the Rainy River dedicated to taking caviar from the eggs of lake sturgeon.

Meanwhile, mining companies placed their hopes on the area as well in their search for gold and other minerals. Numerous mining interests began blasting through the area’s ancient rocks in search of gold, giving immediate rise to small remote communities such as Rainy Lake City, which was a ghost town by 1901, a mere 7 years after its founding.

Minnesota Statehood

Minnesota gained statehood in 1858 and in 1866, the Bois Forte Ojibwe tribe signed a treaty which transferred more than 2 million acres of their homeland to the United States. The young state grew quickly, as its population grew from an estimated 6,000 white residents in 1850, to more than 1.7 million by the year 1900.

Homesteaders immediately began to settle in the state’s northern region and by the 1880s, forests along the Canadian border, including the those of modern-day Voyageurs National Park, were being clear cut in order to provide a constant timber supply for the rapidly growing industrial centers to the south and east.

Public Domain Image*

Logging industry magnates stepped up resource extraction efforts to meet the ever-growing demand. Edward Wellington Backus constructed dams at International Falls in 1910, and at Kettle Falls and Squirrel Falls in 1914.

These dams were built to power sawmills and paper mills in the region, and the logging of white and red pine accelerated. Numerous islands in the area were completely deforested and silt from water runoff began to pollute the waterways.

The Long Road to Parkhood

Such exploitation of Minnesota’s lands became an issue of concern for the state’s residents and in 1891, the state legislature passed a resolution asking the federal government to establish a national park along its northern border. The resolution sought protection for “a tract of land along the northern boundary of the state, between the mouth of the Vermilion River on the east and the Lake of the Woods on the west…”

The proposition of a national park was a divisive subject at the time. Many locals opposed the idea for fear that it would limit hunting and logging in the area. Some simply objected as they saw it as an encroachment of the federal government into local lands.

Ernest Oberholtzer

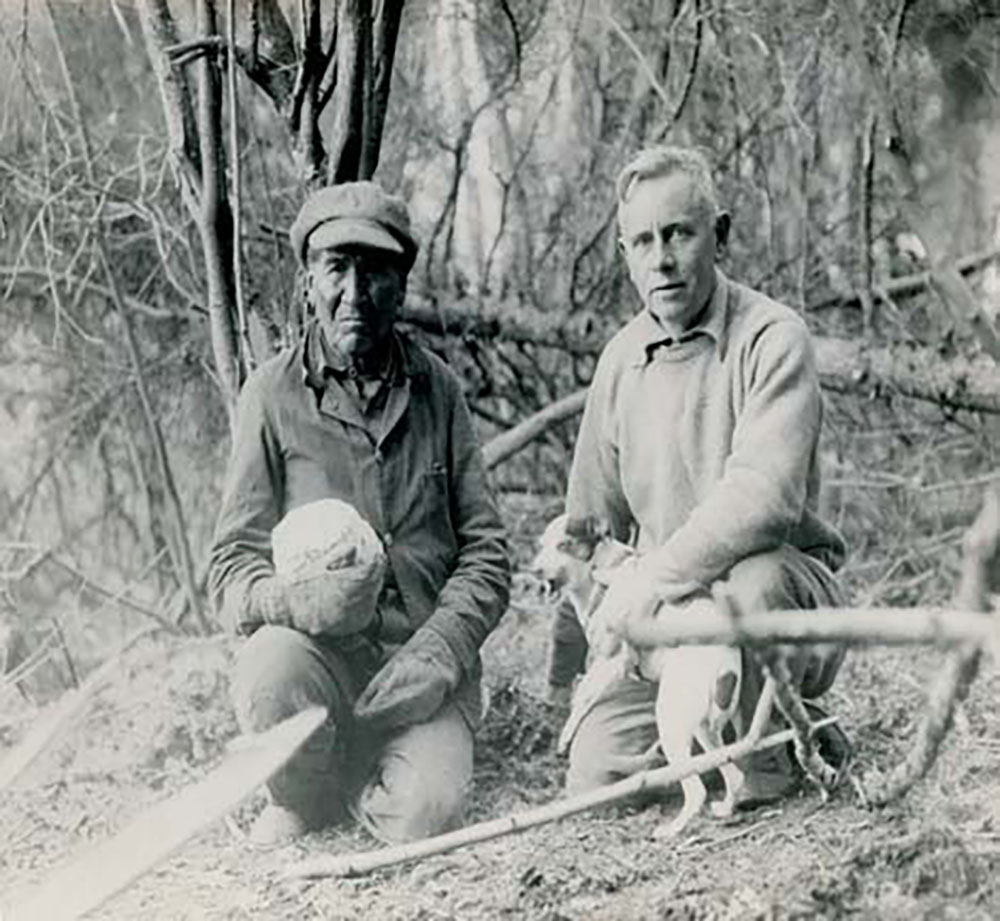

In 1909 a young Iowan named Ernest Oberholtzer came to the Rainy Lake region to paddle the major canoe routes of the large lake’s watershed. With the assistance of an Ojibwe guide named Dedaabaswewidang, aka-Billy Magee, Oberholtzer accomplished his goal during what he termed as his “3,000 mile summer.”

Oberholtzer was born in Davenport, Iowa in 1884 to parents who divorced 5 years later. He was raised by his mother and maternal grandparents in an upper middle-class setting that sent him to Harvard for his college studies.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in 1907, the young Iowan seemed to suffer a bit of wanderlust, spending his time traveling in Europe and paddling the Minnesotan and Canadian waterways. Following his 3,000 mile summer, he became somewhat of an authority on the area and it was quite clear that he held a great affinity for the waterways of Rainy Lake.

Public Domain Image*

In 1915, Oberholtzer entered a business partnership on Rainy Lake, providing guiding services and camping options for travelers and adventurers. The business lasted for a few years, but dissolved seven years after its inception. When it fell apart, Oberholtzer found himself the owner of several islands that the business had held. It seemed logical to just move on up there, construct a few cabins… and call it home.

Meanwhile, the timber industry continued to shave large parcels of land, and in 1925 Backus had introduced proposals to dam the entire Rainy Lake Watershed in order to produce electrical power for his mills. If this were to happen, water levels in the area would raise by as much as 80 feet. Most of what is today Voyageurs National Park would have been submerged.

Oberholtzer began immediately to construct a legal opposition to the dam idea. He worked in concert with a number of friends and comrades to form the Quetico-Superior Council. He enlisted the assistance of his friend and fellow Harvard graduate Sewell Tyng, a New York lawyer who was already familiar with the Rainy Lake area thanks to a number of previous canoe trips he had taken there with his wife.

Tyng took a warlike approach to the issue. According to Oberholtzer, Tyng told the Quetico-Superior Council “were like a lot of farmers with pitchforks against a man with a gatling gun and we must be organized“.

The Council helped pass the Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act of 1930, which prohibited homesteading, the sale of federal land, logging within 400 feet of shoreline, and most importantly in the case of the proposed dams, the alteration of natural water levels.

The construction of the dams would not happen.

Sigurd Olson

Meanwhile, the idea for a national park in the Kabetogama Peninsula needed a local spokesperson who could present the area as worthy of preservation and give it a national audience, while assuaging the more vocal opponents of the local population as well.

Enter Sigurd Olson, a respected wilderness ecologist and writer. Olson knew the area well. He worked in the area as a wilderness canoe guide in the late 1920s, and had purchased a wilderness guide service in nearby Ely, Minnesota in 1929. For the next 30 years, his business provided trips into what would eventually become the Boundary Waters Wilderness Canoe Area.

Sigurd Olson grew up in neighboring Wisconsin, and enjoyed a childhood spent largely in the outdoors. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin in 1922 with a graduate degree in geology, he and his wife Elizabeth moved to Ely, where they would live for the rest of their lives. Olson pursued a variety of interests in academia, teaching high school and then at the university level, ascending to dean of Ely Junior Collage in 1936.

Olson’s outdoor resume was also impressive. His writings gained an ever-widening audience. He became a leading voice in the wilderness preservation movement and served as president of the National Parks Association in the 1950s and helped draft the Wilderness Act of 1964. This position gave him access to a few important political connections, including acting Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.

It would be some time before the request was validated with any substantial interest from Washington. Slowly however, the idea gained a few sympathetic ears and in 1959, the NPS began to investigate possible protections in the Kabetogama Lake region.

Following a NPS field trip to the Kabetogama Peninsula in 1961, Olson and the advisory board submitted a formal recommendation to Udall that the region was “superbly qualified to be designated the second national park in the Midwest”, following the formation of Isle Royale National Park in 1940.

Throughout the following decade, Olson denounced the idea that Voyageurs should be anything less than a national park, speaking publicly and testifying before Congress that the proposed park’s “spiritual and intangible values” were its greatest resource.

Our 36th National Park

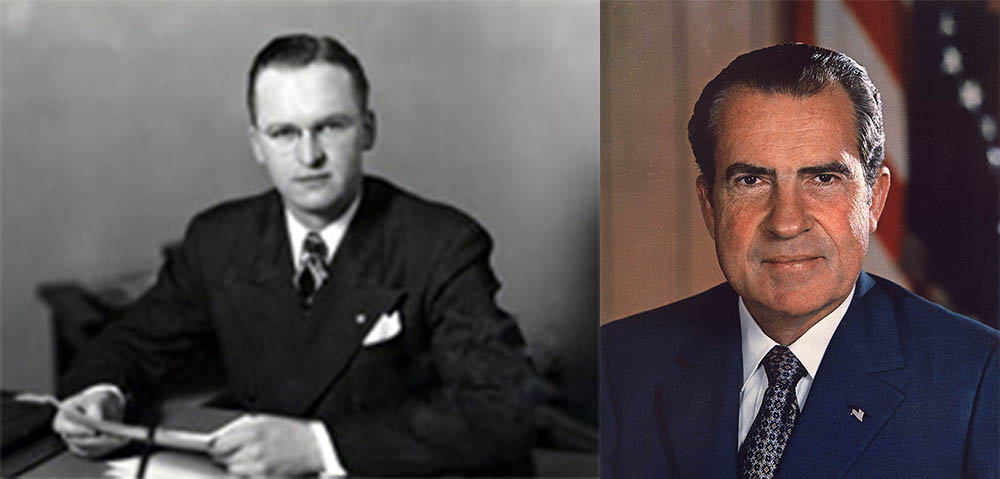

Toward the end of the decade, the effort began to gain traction. In April of 1969, Representative John Blatnik of Minnesota introduced legislation to create what was to be called Voyageurs National Park. It would be nearly a year and half before the bill would pass the House on December 4, 1970, but it passed the Senate just three weeks later on December 22.

On January 8, 1971, some 80 years since the idea first surfaced, the signature of President Richard M. Nixon gave the world a unique national park unlike any other.

The introduction to the bill Nixon signed reads:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the purpose of this Act is to preserve, for the inspiration and enjoyment of present and future generations, the outstanding scenery, geological conditions and waterway system which constituted a part of the historic route of the Voyageurs who contributed significantly to the opening of the Northwestern United States.

Public Domain Images* Blatnik / Nixon

Despite the fact that the park had congressional and executive approval from the federal government, it would be another four years before Voyageurs technically became a national park.

Much of the land comprising the park was held by state and local agencies and many acres were of private holding. It took some time and legal battles to transfer the land to the federal government, and many private holdings became the issue of some contention. Some lands were never transferred, and as of 2020, more than 900 acres of private holdings remain within the park’s boundaries.

The park’s dedication ceremony took place on April 8th of 1975 and Voyageurs National Park became the nation’s 36th national park.

Guide to Voyageurs

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.