Very few of our 62 national parks are decorated with a past that celebrates the nation’s march toward military might. The history of Dry Tortugas National Park is steeped in military prowess and is unique among our parks for not only these reasons, but also for its punishing role during our nation’s darkest hour.

Guide to Dry Tortugas

Discovery of the Dry Tortugas

The earliest history of mankind’s relationship to these remote islands is unknown. No evidence exists which suggests that this area was ever used for any purpose by ancient people, and there are no clues to indicate the presence of early visitors to the Tortugas.

The first recorded notice of this small group of islands came in 1513, by renowned Spanish explorer Don Juan Ponce de Leon. The crew noted abundant wildlife in the area, which was a welcomed find indeed. Large numbers of birds, seals and sea turtles were present, and were easily captured to provide sustenance for the crew.

Ponce de Leon’s records show that his crew captured some 160 turtles while anchored in the islands, along with 14 seals and more than 5,000 birds. The turtles were a treat because they could be kept alive on his ships to provide fresh meat for future meals while at sea.

Ponce de Leon labeled the islands “Las Islas de Tortugas”, or The Islands of the Turtles. Years later, the adjective “Dry” was added to navigational charts to indicate the lack of fresh water.

Spain and Britain hold “Las Tortugas”

In the early 1500s Spain claimed all of Florida, including the Dry Tortugas. More than a century and half later, in 1763, Britain and Spain were at war and the British captured the Spanish port of Havana, Cuba.

Britain was busy building colonies in what would eventually become the continental United States, and Florida was an attractive prize. So the British demanded title to Florida in exchange for Havana. Spain acquiesced and gave Florida to the Brits.

Twenty years later however, the British lost control of the U.S. colonies during the Revolutionary War. Following the war, in 1783, the British ceded Florida to Spain in the Treaty of Paris in order to prevent the United States from acquiring it.

In 1821, the Spanish empire found themselves in trouble and gave up nearly all of their holdings in the western hemisphere, including Florida. The United States added Florida to her holdings for the sum of five million dollars.

The Need for Lighthouses

The islands of the Florida Keys are surrounded by shallow reefs and sand bars. More than 150 shipwrecks, or “casualties” have been documented in the waters surrounding the Dry Tortugas since their discovery in the early 16th century.

Following the purchase of Florida in the early 19th century, the U.S. began building lighthouses throughout the Florida Keys to prevent such unfortunate occurrences.

In 1822, funding for a lighthouse on Garden Key was approved by the United States Congress and construction of the original 70-foot tall beacon began in 1825. However, shipwrecks continued and it became clear that the lighthouse was not tall or bright enough to be effective.

So a new lighthouse was authorized in 1856. This was to be a much taller structure and would be built on the westernmost key of the Dry Tortugas, Loggerhead Key. This lighthouse would stand 152-feet-tall and its brick walls were 8-feet-thick at its base.

The old lighthouse on Garden Key was destroyed by hurricanes in 1875 and a new 75-foot-tall “harbor light” was approved to stand upon Fort Jefferson. This structure was to be built of iron, so it would be less likely to be damaged by cannon fire should the fort ever fall under attack.

Both the Loggerhead Key and the Garden Key lighthouses still stand today. The Loggerhead lighthouse can be seen from miles away, and the park service is in the process of restoring the light as of 2020.

A Young Nation’s Defense

From our nation’s earliest days, it was obvious that The United States lacked a formidable coastal defense. President George Washington organized an early system of forts along the East Coast in the late 1790s, which is historically referred to as the “First System”, to offer protection from offshore attacks.

In the early 1800s, a “Second System” of forts was built that provided substantial upgrades to those of the First System. However, these forts proved woefully inadequate during the War of 1812, as Britain was able to destroy numerous coastal areas and even burn and pillage Washington D.C. and the White House.

Following the war, the need for a more advanced system of fortifications was clear. So a plan was set in motion to develop a “Third System” of structures built of brick, concrete and stone. The new system of forts would also feature bigger and better cannons that would be able to reach ships further out at sea.

This Third System would contain a system of coastal fortification that spanned the entire East Coast, from the north Atlantic, to the Gulf of Mexico, and eventually the coast of California.

Following the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812, military logistical concerns made clear the need for a fort in the lower Gulf. The idea of constructing a fort at the Dry Tortugas was initially rejected by the Navy in 1825, but by 1830, the remote location was reconsidered as an advance post to protect the Gulf Coast.

Construction of Fort Jefferson

Construction began in December of 1846, with the arrival of Lieutenant Horatio G. Wright and George Phillips, a master mason who would be responsible for most of the intricate arches and workmanship found within the fort.

Nearly all of the materials necessary to build the fort had to be imported by ship, as the small islands only provided sand and coral rubble. Every ounce of lumber, cement, iron, slate and of course brick, was brought from the mainland aboard ships that faced harrowing conditions at sea. Many of these ships sank in storms, sometimes within view of the fort itself. Conditions for those involved in the fort’s construction were challenging to say the least.

It took just over ten years of labor to complete the foundation and the first tier. By 1857 there was a massive crew assembled on Garden Key to aid in the construction of the fort.

More than 300 men were stationed on the island at the beginning of the 1860s, and construction of the first tier was well underway. The mood of the nation however, was one of concern. Rumors of war filled the parlors, barrooms and streets of the nation during these years. Strangely, the adversary was not coming from the sea, but from within our own borders.

Fort Jefferson Prepares for Civil War

As the U.S. marched toward internal war in 1860, a new commander arrived to oversee efforts at Fort Jefferson.

Captain Montgomery C. Meigs arrived in the Dry Tortugas as tensions were rising on the mainland. His route to the fort had taken him directly through the southern states, where he had heard the battlecry of the southern resistance firsthand. Meigs knew that war was imminent.

Arriving at the fort, the newly appointed Meigs was aghast to discover that he had little in the way of defense if any form of violence was to arrive at his doorstep. Although the foundation and the first tier appeared adequate, the commander found that the fort did not yet contain a single cannon.

Meigs immediately ordered all openings shuttered and the drawbridge over the moat to be completed. He also hastily arranged for a shipment of guns which would at least provide a relative measure of security.

Fort Jefferson in the Civil War

On January 10, 1861 Florida seceded from the Union and with the state’s separation came Confederate control of most the coastal forts that stood on the state’s mainland. Fort Jefferson and Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West however, would remain under Union control for the duration of the conflict.

Union control of this strategic location enabled the North to control the waters and shipping lanes along the Gulf Coast and to offer ready supply lines to Union warships that patrolled these waters for the duration of the war.

The war began with the Confederate firing on Fort Sumpter in April of 1861. Although many thought the war would not last long, preparations continued at Fort Jefferson with the mounting of 65 guns, including 24-pound howitzers and 8-inch columbiads. More guns were also amassed at the fort, but were never mounted.

With the Union’s lack of control over the majority of southern territory, the need for a prison to house captured Confederate soldiers meant that Fort Jefferson would be receiving guests. The first 33 prisoners were delivered to the fort in September of 1861. The population of Garden Key was somewhere in the realm of 400 by the end of that year.

The following spring, Union troops from New England arrived to protect the fort, bringing the island population to 1,400. Prisoners continued to flow into the tropical paradise during the next three years of the war and by November of 1864, Fort Jefferson held 882 Confederate prisoners.

Conditions declined as hunger, thirst and disease became a constant source of misery for those serving sentences on what became known as Devil’s Island. By the end of the war, there were 768 prisoners at the fort, and despite the war’s termination, the prison remained active for several more years.

Is Dr Mudd in the House?

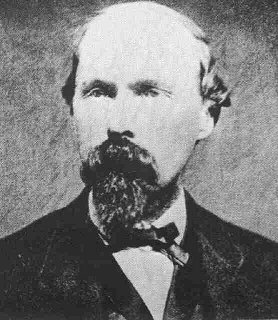

Most of the prisoners that were held at Fort Jefferson were southern soldiers who were captured on the battlefield, but a few civilian prisoners were sent there as well. The most famous of these unfortunate souls was Dr. Samuel Mudd, the doctor who splinted the leg of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, the notorious John Wilkes Booth.

Dr Mudd had been charged and convicted as a conspirator in Lincoln’s assassination and had only escaped the death penalty by one vote. In the summer of 1865 he arrived at Fort Jefferson to serve a life sentence. A foiled escape plan was the highlight of his first two months on the island, but the doctor settled in nicely over the following two years.

Public Domain Image*

Little did Mudd know, but his medical skills would provide his eventual escape. In 1867, the majority of the fort’s residents became ill with Yellow Fever. At this point, only 54 prisoners remained, as most had been removed. Nevertheless, there were nearly 400 people still residing within the walls of the fort, including soldiers, engineers, laborers, doctors and nurses.

The disease spread quickly in the humid fort and by the fall, more than 270 cases of Yellow Fever were present. The fort’s surgeon, Dr. Joseph Smith, was one of the first to die, followed by four nurses and the surgeon’s young son. Fear was overtaking the island and Dr Mudd volunteered to take charge of the medical responsibilities in the fort.

The disgraced doctor’s skill and effort saved lives and by the end of the outbreak, only 38 of more than 300 cases resulted in death. Mudd became sick as well, but recovered as the epidemic slowly passed and relative health returned to the fort’s residents.

Mudd received a pardon in 1869 from President Andrew Johnson in response to his actions during the Yellow Fever outbreak. Upon his release, the doctor returned to his Maryland farm where he would die in 1883 at the age of 49.

After the War…

Construction would continue for another 20 years before it became clear that continued efforts toward completion would be futile. Of course the interruption of construction due to the Civil War had done little to advance the completion of the fort.

By 1884, the fort’s design was essentially obsolete by military standards. Newly designed rifled cannons were much more powerful than their predecessors and the masonry walls of Fort Jefferson would not withstand prolonged bombardment from such weapons.

In addition to the threat posed by newly designed machines of war, the fort was already in bad repair, with crumbling architecture and leaking cisterns. Studies also began to indicate that the sheer weight of the fort was slowly forcing the submersion of Garden Key. Although the fort was near completion, its construction was abandoned in 1884 as Congress would not appropriate more funds for the now obsolete fort.

An Abandoned Fort

Fort Jefferson was found useful for a number of military applications in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Spanish-American War saw the fort used as a hospital, treating U.S. troops wounded in the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in 1898 in Havana, Cuba. This ship had been anchored in the Dry Tortugas prior to its passage to Cuba.

The Navy used Garden Key as a coaling station during the early 1900s until a hurricane severely damaged the docks and officers’ quarters in 1910. The Navy declined to appropriate funds to reconstruct the damaged facilities and the fort was subsequently abandoned.

Creation of Dry Tortugas National Park

The Dry Tortugas received a shout out in 1908 from none other than Theodore Roosevelt, when he named the islands a federal bird reservation. Although the fort was used as a radio transfer station and a seaplane base in World War I, and again as a harbor for defensive torpedo boats, minesweepers and convoy escort vessels in World War II, it was clear by this point that the fort’s usefulness was fading into history.

In 1935, President F.D.Roosevelt created Fort Jefferson National Monument and the National Park Service undertook the management of the historic fort and its surrounding waters and islands.

The park’s boundaries were expanded in 1983 and in October of 1992, the United States Congress established Dry Tortugas National Park, “to preserve and protect for the education, inspiration and enjoyment of present and future generations nationally significant natural, historic, scenic, marine and scientific values in South Florida”.

Guide to Dry Tortugas

Relevant Links

Yankee Freedom III – Ferry Service

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.