Biscayne has a rich history that dates back to the early 20th century, when Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe proposed the protection of Biscayne Bay as part of his plan for the Everglades.

After years of political support and advocacy, Biscayne National Park was established in 1968 as a national monument, and was later expanded to include more of the bay and offshore reefs.

Biscayne Guide

Early Peoples

Archeologists estimate that Native Americans inhabited the lower parts of Florida around 10,000 years ago. With rising water levels around 4,000 years ago, the Bay became submerged, making it impossible to find traces of that era on dry land in the park. The earliest known evidence of human presence in the area dates back to 2,500 years ago when piles of conch and whelk shells left behind by the Glades culture were discovered.

The Tequesta people, who lived on the shores of Biscayne Bay, followed the Glades culture. The Tequesta lived a sedentary life, surviving on fish and other sea life and showed no significant agricultural activity. Today, the park has identified about 50 significant archaeological sites.

Early Explorers

In 1513, Juan Ponce de León, a Spanish explorer, arrived in Biscayne Bay and discovered the Florida Keys, encountering the Tequesta people on the mainland. He referred to the Bay as “Chequescha,” and later, “Tequesta” by the time Spanish Governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés arrived later in the century.

The area eventually came under Spanish rule, and the Tequesta people were resettled in the Florida Keys, leading to the depopulation of the mainland. The Bay’s waters saw the passage of the Spanish treasure fleets that were often caught in hurricanes, leaving 44 documented shipwrecks in the park from the 16th through the 20th centuries. HMS Fowey was one of the wrecks discovered in what is now Legare Anchorage. The discovery of the wreck led to a court case that established the wreck as an archaeological site rather than a salvage site.

The first permanent European settlers in the Miami area arrived in the early 19th century. The first settlements around Biscayne Bay were small farms on Elliott Key, growing crops like key limes and pineapples.

Keeping up with the Jones’

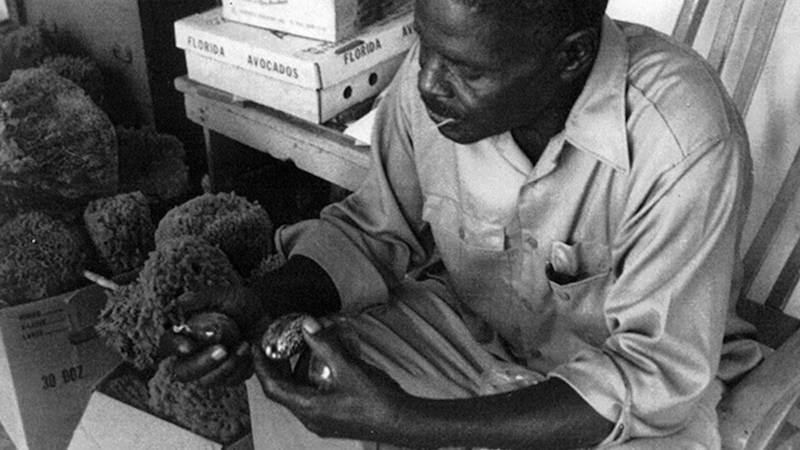

Few people lived in the park area until Israel Lafayette Jones, an African-American caretaker, bought Porgy Key for $300 US in 1897. The next year, he bought the adjoining Old Rhodes Key and moved his family there, clearing land to grow limes and pineapples. In 1911, Jones bought the 212-acre Totten Key, which had been used as a pineapple plantation, for a dollar an acre, selling it for $250,000 in 1925.

At the time of Jones’ death in 1932, the family’s plantations were among the largest lime producers on the Florida east coast. The farming operations were taken over by his sons, King Arthur and Sir Lancelot, who experience a decline in production due to damages from the Great Hurricane of 1926.

The brothers soon found a business success with a fishing guide service, and through the coming decades would host a number of prominent business and political leaders such as Herbert Hoover, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

Some 40 years later, an aging Lancelot, along with Arthur’s widow Kathleen, would sell their home to the National Park Service for $1.2 million dollars. Lancelot chose to stay on the island for another 32 years. It didn’t really seem he cared about the money.

High Society

Biscayne Bay’s beauty has attracted many visitors throughout the years, with many building recreational clubs, such as the Cocolobo Cay Club built by Carl G. Fisher in 1922. The two-story club building had ten guest rooms, a dining room, and a separate recreation lodge. Patrons included Warren G. Harding, Albert Fall, T. Coleman du Pont, Harvey Firestone, Jack Dempsey, Charles F. Kettering, Will Rogers, and Frank Seiberling.

Boca Chita Key was once the private getaway for business tycoon Mark Honeywell, who is responsible for the small island’s signature lighthouse, which still stands today. Built in the 1930s, largely as an ornamental decoration, the lighthouse was never meant to actually provide aid to ships, but probably did help a few intoxicated guests make their way back toward the party, after a drunken tussle in the mangroves.

Stiltsville

Other clubs would pop up as well in a small waterborne community that became known as Stiltsville, which grew from the 1930s post prohibition era, to enjoy a rebellious reputation as a haven for illegal gambling, prostitution and alcohol.

Residents here constructed shacks that stood atop stilts, floating above Biscayne Bay, miles from the rules and regulations of the nearby mainland shores. Hard-partying outlaw establishments such as Crawfilsh Eddie’s, the Quarterdeck Club and the appropriately named Bikini Club sprang up above the stilts, and found themselves flooded with party-seeking visitors from the mainland.

The Bikini Club was known to serve free drinks to ladies dressed in the namesake attire, and legends of wild parties soon made this unlicensed bar the focus of law enforcement efforts in the 1950s, which brought about its end.

At its peak in 1960, Stiltsville was home to 27 structures, but hurricanes, law raids, fires and life at sea took their toll. Eventually, the community mostly just blew away. Today, only seven structures remain.

Islandia & Development

Developers in Miami looked to southern Dade County for new projects, viewing the undeveloped keys south of Key Biscayne as prime territory.

In the 1960s, the City of Islandia was created on Elliott Key, incorporated to encourage Dade County to improve access to Elliott Key, which was seen as a potential rival to Miami Beach. The new city lobbied for causeway access and formed a negotiating bloc to attract potential developers. One vision of Islandia, supported by landowners, would have connected the northern Florida Keys – from Key Biscayne to Key Largo – with bridges and created new islands using the fill from the SeaDade channel.

Meanwhile, plans were proposed for SeaDade, an industrial seaport that would have included an oil refinery and required dredging a 40-foot-deep channel through the bay for large ships to access the refinery.

A group of early environmentalists, led by Lloyd Miller, Juanita Greene, and Art Marshall, opposed the development of the bay and proposed the creation of a national park unit that would protect the reefs, islands, and bay. Miami Herald editors, as well as Florida Congressman Dante Fascell and Florida Governor Claude R. Kirk, Jr., supported the park proposal, which was also backed by lobbying efforts from sympathetic businessmen including Herbert Hoover, Jr.

In 1968, when it appeared the area was about to become a national monument, Islandia supporters bulldozed a six-lane-wide highway down the center of Elliott Key, destroying the forest for 7 miles. The highway was called Elliott Key Boulevard by landowners, but “Spite Highway” privately.

Over time, the forest grew back, and the only significant hiking trail on Elliott Key now follows the path of Elliott Key Boulevard. In addition to the Spite Highway, Turkey Point Power Station was completed in 1967-68 and experienced immediate problems from the discharge of hot cooling water into Biscayne Bay, where the heat killed marine grasses.

1980 – Biscayne National Park

The establishment of Biscayne National Park can be traced back to the early proposals of Everglades National Park advocate Ernest F. Coe. Coe’s proposed Everglades park boundaries included Biscayne Bay, Key Largo, and the interior country, but Biscayne Bay was cut from Everglades National Park before its establishment in 1947.

In 1960, proposals to develop Elliott Key prompted Lloyd Miller to ask Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall to send a Park Service reconnaissance team to review the Biscayne Bay area for inclusion in the national park system. A favorable report ensued, and with financial help from Herbert Hoover, Jr., political support was solicited, most notably from Congressman Fascell.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Public Law 90-606 to create Biscayne National Monument on October 18, 1968, and the monument was later expanded in 1974. The bay and its keys were promoted to National Park status by an act of Congress and the signature of President Jimmy Carter on June 28, 1980.

Biscayne Guide

Relevant Links

Biscayne National Park Institute