Each national park has a history. Historians often weave romantic tails of how an idealistic individual, or group of individuals worked tirelessly to preserve a landscape for the sake of simply preserving a landscape.

The history of Acadia National Park is one such story, but this park’s path to preservation reveals a level of altruism beyond that of most other parks.

Guide to Acadia

Early People

Following the retreat of the Wisconsin Glaciation some 17,000 years ago, the newly revealed landscape of Maine began to accept newcomers. Plants began to grow in sparse parcels of soil that slowly blew into the region and small trees took root as conditions allowed.

Over the course of time, biomass from dead plants became soil and the land developed to support larger and more diverse forms of life. Animals slowly wandered northward and began to thrive in a newly developed wilderness.

With the bounty of nutrients available from an array of plants, animals and sea life, it was only a matter of time before humans would enter the area in search of sustenance and safety.

The region’s earliest human inhabitants descended from Ice Age hunters, who were likely present not far after the retreat of the great glaciers, although evidence can only suggest their presence in the range of 12,000 years ago. Little is known of their time in this area, and there are only scant records of their activity here, such as scattered bits of bone and crude stone tools.

Red Paint People

A few thousand years later, a group emerged that are known as the Red Paint People, because they would line the graves of their dead with red clay. Their time here appears to have been a time of plenty, judging from the massive heaps of oyster and shellfish remains which date to nearly 5,000 years ago. In addition to these delicacies, it appears the Red Paint People were successful in the hunting of the elusive swordfish, which would provide great sustenance, as well as material for intricate bone ornaments.

Wabanaki

More recent times witnessed the formation of four distinct tribes in the Maine area: The Maliseet, Micmac, Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot. These tribes are referred to collectively as the Wabanaki, or the “People of the Dawn”. They were skilled artisans and hunters, and were able fishermen in seaworthy ash and birchbark canoes.

Public Domain Image

The Wabanaki have held Maine, or Wabanakik, “Land of the Dawn”, as their homeland for at least a couple of thousand years. Mount Desert Island was a central location for the Wabanaki, and they hunted and fished in the forests and waters that today comprise Acadia National Park. They referred to the island as “Pemetic”, a word meaning “sloping land”.

Public Domain Image.

As time saw the advance of European settlements along the coast of Maine, the Wabanaki would trade with the newcomers and sell their handmade canoes to wealthy travelers. Samuel de Champlain noted in his writings that the Wabanaki people had quite a few European goods, indicating a healthy relationship between the Wabanaki and seafaring people prior to the French explorer’s arrival in 1604.

Early visitors to the area could witness native dance performances in Bar Harbor and Sieur De Monts, and Wabanaki guides led canoe trips around the Cranberry Islands and Frenchman Bay.

Samuel de Champlain

The world was shrinking quickly in the 1600s, and French explorer Samuel de Champlain was cruising the northern coasts of the “new world”, in search of land that he could claim for the French crown and that would provide good land for settlement.

Upon spotting the barren outline of Cadillac Mountain, with its smoothed rock summit rising above all else, Champlain declared it “l Isle de Monts Deserts”, or “the island of the bare mountains”. Champlain made contact with the Wabanaki encountered a hospitable welcome.

No authentic depiction of Champlain is known to exist.

Public Domain Image

Although Champlain and the French held interest in the region, there was little they could do to protect the land from foreign encroachment. The area that would one day become Acadia National Park lay relatively undisturbed for nearly 150 years as Natives, the French and the English exchanged rights to the island and surrounding areas numerous times, although the land was only seasonally occupied.

At one point, an ambitious young named Frenchman Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, who later founded the city of Detroit, held the island along with a vast swath of Maine coastline. He & his bride lived in the area for a while, before abandoning their attempt to settle the area and heading west.

French holdings in the area were soon lost to the English and were later sold to American settlers following England’s loss in the Revolutionary War.

Early Settlement

At the turn of the 19th century, Maine remained an outlier of civilization. Nevertheless, the island of Mount Desert held a few small communities which sustained themselves on fishing and shipbuilding. By the early 1820s, this social structure had began to change, as farming and lumber extraction shared the spotlight as prevalent means by which residents made a living.

Farmers worked fields of corn, potatoes, rye and wheat while hundreds of acres of wooded terrain were cleared to provide lumber for ships and various smaller wooden products.

The Rusticators

The mid-19th century welcomed newcomers to the area, as the United States began to expand, and its citizenry looked outward toward the horizons of a new nation. During these years, artists, professors, philosophers and other intellectuals who were commonly known at the time as “rusticators” began to visit the area in search of artistic inspiration.

These travelers sought to escape the confines of society and to experience the simplicity of life in exotic locations and Mount Desert Island gave them perfect refuge. They spent days hiking from place to place on the island, exploring the hills and valleys while enjoying the simple beauty of the natural setting.

Public Domain Image

Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, painters from the Hudson River School were among these rusticators. Cole’s artwork, notably “View Across Frenchman’s Bay from Mt. Desert Island After a Squall“, was among the first to bring the stunning scenes of Mount Desert Island to the general public.

Acadia’s Cottagers

Following the publication of such works, the crowds began to descend on the area. By 1860, direct steamboat service to Mount Desert Island was available from Boston, and in the 1880s, a railway provided locomotive access to the blossoming tourist center.

Soon, the island became known as the playground for East Coast elites. Wealthy business titans began to buy up prime parcels and construct luxurious homes along the waterfront that were referred to as “cottages”.

Families such as the Carnegies, Fords, Morgans, Rockefellers and the Vanderbilts spent their summers here throughout the “Gay Nineties” and by the turn of the 20th century, Bar Harbor was quickly transforming from a community favored by the simple rusticators, to an exclusive playground for the rich.

Charles Eliot

As the wilderness of Mount Desert Island continued to shrink, and the number of mansions (cottages) continued to swell, a few of the island’s summer residents began to sense that the unfettered growth of the area would soon ruin the small, quiet essence of the island. A young man named Charles Eliot grew concerned that the wild areas of Mount Desert may not remain wild if the current trends continued.

Charles was the son of Charles William Eliot, an aristocratic property owner on the island and the President of Harvard University, having achieved the position at the ripe age of 35. He remains the youngest president in the school’s history, as well as the longest serving, holding the prestigious position for 40 years.

The younger Eliot spent his summers on Mount Desert Island and his time wandering about the island’s natural habitat had affected his worldview in a profound manner. While in school at Harvard, he organized a group of college classmates who formed the Champlain Society.

Public Domain Image

They would sail to Mount Desert each summer and engage in the study of botany, entomology, geology, meteorology and ornithology. After his time at Harvard, the young Eliot went on to work with Henry Law Olmsted, eventually gaining a position as a partner in the Olmsted firm with Henry’s sons.

Over the course of his years on the island, the young Eliot became concerned that the pace of growth would soon lead to an irreversible privatization of the island’s most scenic vistas.

Young Charles placed his concerns in an article that he was writing for publication in Garden and Forest, a popular horticulture journal of the 1880s. His article noted the increase in private land ownership on the island, and surmised that this may in time eliminate public access to many of the spectacular scenes that made the island so attractive in the first place.

It is time decisive action was taken, and if the state of Maine should encourage the formation of associations for the purpose of preserving chosen parts of her coast scenery, she would not only do herself honor, but would secure for the future an important element in her material prosperity.

Charles Eliot – circa 1888

Unfortunately, the younger Eliot suffered from meningitis and his untimely death at the age of 38 prevented him from acting to formulate his idea for the island’s preservation. However, his father later found a copy of his son’s writings and began to take actions of his own to see that his son’s dream did not fade away.

In 1901, the senior Eliot began to present his son’s ideas to other wealthy community members who had formed what they called “Village Improvement Societies”. The elder Eliot, reminded his neighbors that some of their favorite areas were being purchased by others, who may in time, act to restrict public access to such areas.

Public Domain Image

Eliot proposed that the Village Improvement Societies create a special organization to set aside special lands for the public benefit. His neighbors responded in accordance, and in September of 1901, the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations was incorporated with the express purpose of “…acquiring, owning and holding lands and other property in Hancock County for free public use“.

Although the plan was slow to take off, residents slowly began to donate property to the organization. As donations of land increased, the Mount Desert Island’s tax base began to take a hit, and the Trustees of Public Reservations’ tax exempt status was soon challenged at the state level.

Although the challenge would be defeated thanks largely to the efforts of George Dorr, the writing was on the wall. There would be more challenges to the group’s status as more tax dollars were removed from state & county coffers.

George Dorr – Father of Acadia

One of Eliot’s fellow trustees and preservation advocates was his island neighbor, a wealthy heir to a textile fortune and a fellow Harvard alumni named George Dorr. While Eliot had the island’s local preservation on his mind, Dorr had much greater plans for the island.

George Buckhnam Dorr was born in 1853 in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, to wealthy Bostonians Charles Hazen Dorr and Mary Gray Ward, who held massive fortunes that were gained in the textile industry.

Public Domain Image

Dorr’s childhood was spent in an idyllic manner, as he reported later of his grandfather’s rural home in Canton: “There, in real country, with woods and a lake for neighbors, dogs and horses for companions, my bother and I grew up, springs and falls, till college days”.

Dorr suffered from a stutter at a young age, and it appears he never completely overcame it, but it certainly does not seem to have affected his influence in social settings. He went on to graduate from Harvard, and to chair the Harvard philosophy department’s visiting committee for nearly two decades.

During this time Dorr led fundraising efforts for a new campus building, Emerson Hall, and learned the skills of negotiation, planning and management that would assist him during later efforts on Mount Desert Island.

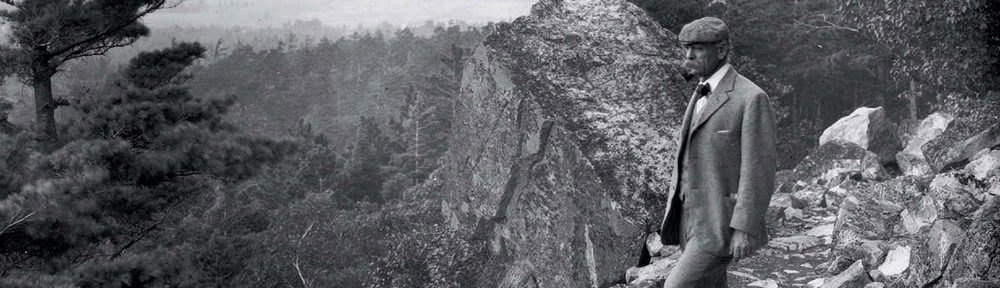

Young Dorr first visited Mount Desert in 1868, at the age of fifteen while on vacation with his parents. During that visit, the family purchased a 58 acre parcel in Compass Harbor that would become known as Old Farm. Ten years later, a 30 room home was built, which would eventually become Dorr’s primary home for much of his life.

Dorr grew to be an eccentric bachelor, who insisted on a daily swim in Frenchman Bay, even during times when he had to chip away ice at the shore to enter the water. His hikes took him all over the island and his time and energy was largely spent focused on the island’s preservation.

Public Domain Image

He became involved with Eliot’s efforts to preserve the island in 1901, taking a position as Vice President of Trustees. Following the tax exempt challenge to the Trustees of Public Reservations, Dorr & Eliot realized that if they lost tax exempt status, their plan would quickly become bankrupted.

Dorr was insistent that a greater level of protection must be sought. In his mind, their holdings would continue to be vulnerable unless they could be given federal protection in the form of a national park.

Eliot was onboard, and with his blessing, in 1914, Dorr headed to Washington D.C. with a generous gift for the nation. Dorr held the deed to some 5,000 acres of Maine’s most scenic shoreline.

Sieur de Monts National Monument

Once in Washington, Dorr met with influential friends and began to work his way up the ladder. His skills of negotiation came in handy, as he convinced bureaucrat after bureaucrat that his gift was worthy of consideration by the next level up. Finally, after two years of insistence, his plans were presented to President Woodrow Wilson.

The Trustees, along with Dorr were hoping for a national park, but lacking the Congressional votes to make this happen immediately, they settled for the next best thing. In July of 1916, one month prior to the creation of the National Park Service President Wilson created Sieur de Monts National Monument.

Dorr’s efforts were fully rewarded three years later, when on February 6, 1919, the same day that Arizona’s Grand Canyon obtained national park status, Congress created Lafayette National Park, named for a Frenchman who advocated American independence.

The park named George Dorr as its first superintendent. The eccentric bachelor accepted the salary of $1 per year for his duties. He believed initially that his inheritance, combined with his earnings from Mount Desert Nurseries, a small business he had started, would continue to enable the purchase of lands on part of the park throughout his life, but this was not the case.

As he aged, his duties in furtherance of the park idea would not suffer, but his monetary fortunes would. By 1929, when the park was enlarged and renamed Acadia National Park, his finances were dwindling and he began to accept a regular salary.

George Dorr would hold the position as Park Superintendent at Acadia until his death in 1944, at the age of 90. His later years were complicated by failing health. He suffered a heart attack at age 80 during one of his morning swims, and doctors gave him six months to live. He refused to go however, and lived for another decade, during which he would lose his sight, and suffer financial woes that left him destitute.

George Dorr’s commitment to the public access of these lands cannot be understated. After all was said and done, there was only enough money to cover his funeral expenses, because a family accountant had secretly set aside $2,000 for that purpose.

The Father of Acadia gave all he had to his park…

Rockefeller’s Carriage Roads

Around the time George Dorr was fighting to retain the tax exempt status of the Trustees of Public Reservations, another wealthy individual was making moves to improve access to the interior scenery of Mount Desert Island.

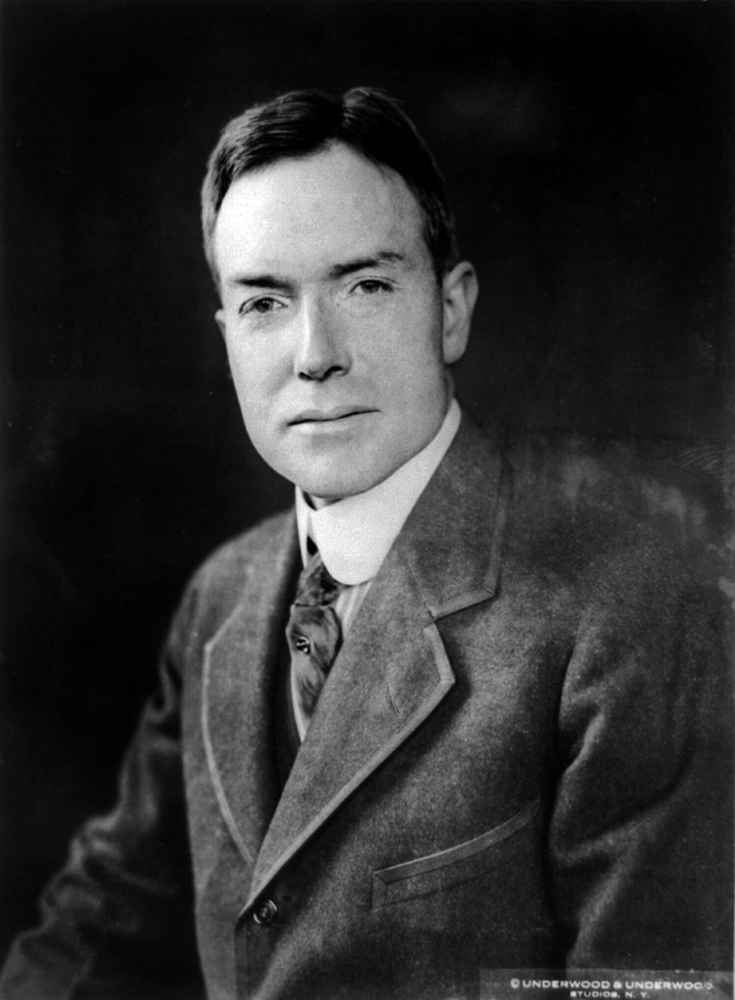

John D. Rockefeller Jr. had already donated thousands of acres to the park, but was fond of the idea of building a system of roads through the most scenic areas of the island. These roads however, would be absent of the automobile, the numbers of which were increasing on the small streets and roads of Mount Desert Island.

Public Domain Image

These roads would serve only horse-drawn carriages and hikers and were termed “carriage roads”. Rockefeller had experience in the techniques of road building, as his father, John D. Rockefeller Sr., the founder of Standard Oil, had overseen the construction of numerous such roads at his estates in Ohio and New York. Young Rockefeller Jr. had paid close attention to the details of road building and saw the perfect opportunity to connect various areas of Mount Desert Island with such roads.

Rockefeller laid out the routes of the roads, painstakingly walking mile after mile examining the slope of each hill and designing a route that would apply minimal impact to the natural landscape. He proved to have a instinctive gift for the process and his routes maintained slopes that are not too steep, nor too sharply curved to allow the easy passage of a horse-drawn carriage.

The park’s carriage roads are a fine example of broken-stone-roads – a type of road that was typical of the early 20th century. Most areas maintain a width of around 16 feet, while providing adequate drainage for coastal Maine’s wet winters and springs. Granite stones were quarried locally and used to create culverts, ditches, side coping stones, and of course, the beautifully exquisite gates and bridges that today present an immediate image of classic Acadia to the everyday visitor to the park.

All told, Rockefeller’s road building project took 27 years, and created about 57 miles of roadway. Nearly all of the financing for the project was provided by Rockefeller. Legend has it, that the wealthy oil man once told George Dorr that for what the roads cost him, he could have just as easily constructed them of diamonds….

Park Loop Road

But Rockefeller wasn’t done. As the progression of society moved toward a more auto friendly society, more visitors began to encourage the use of autos on the park’s carriage roads.

Rockefeller would hear nothing of it. But sensing the inevitable, he began the process of constructing the Park Loop Road, which he called the Acadia Park Motor Road, primarily as a means by which he could keep the motorized carriages away from his carriage roads. The roadway was designed by none other than Fredrick Law Olmsted Jr, and took nearly 20 years to complete.

“The whole theory of the Acadia Park Motor Road is that there shall be a continuous, unbroken-by-highways, park road circuit to the top of Cadillac Mountain, down to the sea, for miles along time seacoast and back to Cadillac Mountain.”

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., August 22, 1939

Today, visitors to Acadia can drive the 27-mile park road, although reservations are now required. Guests can also access about 45 miles of the carriage roads on foot, bicycle, horseback or by horse-drawn carriage. Any visit to Acadia should at least include a stroll or a ride on one of these historic roads. There are simply none like them anywhere else.

Acadia Today

As the twentieth century progressed, the park witnessed the expansion of the National Park Service and the continually increasing popularity of the national park idea. Acadia would continue to expand, as more acreage was added in 1929 and again in 1986. Today the park holds some 47,000 acres and greets nearly 3.5 million visitors per year.

As park visitation numbers continue to increase, the park service is beginning to implement restrictions on auto travel within the park. As of 2021, Acadia requires reservations & a fee to travel on the Park Loop Road and to access many of the park’s more popular areas.

History continues in Acadia, and the 21st century provides many concerns for the park. Hopefully, the generous spirit of visionaries such as Charles Eliot, George Dorr and J.D. Rockefeller Jr. continues to inspire the future leaders of the park and its surrounding areas…

Guide to Acadia

Relevant Links

National Park Guides

All content found on Park Junkie is meant solely for entertainment purposes and is the copyrighted property of Park Junkie Productions. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited without the express written consent of Park Junkie Productions.

YOU CAN DIE. Activities pursued within National Park boundaries hold inherent dangers. You are solely responsible for your safety in the outdoors. Park Junkie accepts no responsibility for actions that result in inconveniences, injury or death.

This site is not affiliated with the National Park Service, or any particular park.